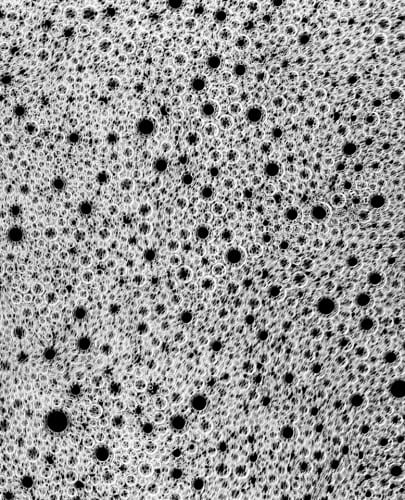

Marco Breuer’s studio during his 2016 residency at Headlands Center for the Arts (artwork © Marco Breuer; photograph by Andria Lo, provided by Headlands Center for the Arts)

In 2015, Headlands Center for the Arts announced a new residency award: the Larry Sultan Photography Award. With partners Pier 24 Photography, California College of the Arts (CCA), and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), Headlands created the Larry Sultan Photography Award as an extension of the established Larry Sultan Visiting Artist Program, which brings exemplary artists to the Bay Area to engage with the arts community through a public lecture and guest critiques with students at CCA. The new initiative with Headlands establishes an additional layer of cross-pollination for the awardees by providing them with six-to-ten-week residencies at Headlands, which offers private studio space and living accommodations within an interdisciplinary community of creative practitioners. Headlands’ discipline-specific residency awards (including awards for painters, artists working in social practice, and a drawing and painting teaching fellowship in partnership with the San Francisco Art Institute) unfurl the ways in which a residency can be both an opportunity for internal focus on the nuances of an artist’s primary discipline and an opportunity to forge new relationships amid a myriad of external forces: adapting to a new studio set-up; forming relationships with practitioners in other disciplines; and presenting and discussing work at academic institutions, neighboring arts organizations, or commercial galleries.

While each of the Headlands discipline-specific residency awards is uniquely shaped to meet the particular needs of the artist and discipline, the awards simultaneously bring recipients into a sphere of discourse that is not so neatly delineated—where boundaries between disciplinary modes are productively diffused. The inaugural Larry Sultan Photography Award recipient, New York–based artist Marco Breuer, whose work embodies this discipline-defying diffusion aptly: Breuer’s photographs are often created through camera-less methods, where an image is not merely recorded, but is physically created through the catalytic action of one material coming into contact with chemically sensitive photo paper. The tools of Breuer’s photographic practice throughout his twenty-five-year career have included twelve-gauge shotguns, electric frying pans, razor blades, power sanders, and turntables. His immense body of work shows formal complexities and mercurial impressions that are often the result of simple, perhaps even mundane, gestures. Below, Breuer and I discuss how his practice has mandated an openness to the unfamiliar from the outset, and the ways in which a residency’s newness of place can be a generous offering to the creative process. Our conversation took place in Breuer’s studio at Headlands, on April 13, 2016.

–Vanessa Kauffman

Marco Breuer, Motion (C-872), 2008, chromogenic paper, exposed, unique, 13-3/8 x 10-1/2 in (33.9 x 26/6 cm.) (artwork © Marco Breuer; provided by the artist and Yossi Milo Gallery)

Vanessa Kauffman: You live in rural upstate New York. Many of the artists-in-residence at Headlands have to acclimate to being as removed as we are from the city (about twenty minutes from San Francisco) when they arrive; I imagine there is a reverse acclimation for you, here where there is more urban or social stimulation than in your daily life.

Marco Breuer: I live about four hours from the city, so I’m far from the people I work with professionally. At the Headlands, I’m only a few minutes away from them. Being here is a reversal for me—I love being so close to San Francisco. I have use of a vehicle here, so I can just pop in and out of the city.

I was in Manhattan for thirteen years and it seemed like it had been enough time. My wife Mina and I bought some land and we got into farming. We raise animals, and we started a small, experimental artist residency ourselves. We’ve had five or six painters and sculptors come over the years—we give them a studio space and house them in an old school bus. It’s been interesting to see a residency from the facilitator’s perspective. It’s small—essentially artists we know well and want to spend time with—and it’s not intended to grow into something bigger. The idea for it came about because we have big barns and a lot of space and since we are so remote, we thought we’d bring people to us. I go into the city when I need to—it’s close enough. I have facilities I use there: darkrooms and print shops.

Kauffman: What projects are you working on while you’re in residence?

Breuer: I’m doing a couple of different things. To start, I’m working on my next show, which will be at Yossi Milo Gallery in the fall. I’m experimenting with new materials, because of access to equipment here that I usually don’t have. Since I’m working with an assistant here, which I rarely do, I’m doing some camera-based work. For now, I think the images are going to be published in a newsprint tabloid, but it might morph into a larger book project.

I publish regular trade edition books and artist books as often as I can, but I also use the book format as a way to think through other bodies of work. Sometimes the books are part of a show or a way to get work out into the world, but sometimes they stay in my studio and help me to get into a project, generate ideas, or think through aspects like sequencing and juxtaposition for an exhibition.

Marco Breuer’s studio during his 2016 residency at Headlands Center for the Arts (artwork © Marco Breuer; photograph by Andria Lo, provided by Headlands Center for the Arts)

Kauffman: Your work is full of gesture, which removes it from any specific place but also gives it intimacy. The marks in your images could represent any moment, any place.

Breuer: The work has become gestural over time. I used to work with self-recording phenomena, photograms, and that was tied to objects. In these current projects, the work is much more about line and color. When you’re starting out after school, you’re trying to claim some space for yourself, and you’re trying to define who you are as an artist. If you have a contrarian personality, like I do, you do it by deciding who you’re not. But that’s not a sustainable mode—you can’t work in opposition for thirty years. Eventually you realize it doesn’t matter what other people do—what matters is what you do and the choices you make—and you have to own those choices. For me, that meant moving away from more automatic or chance-driven work to making concrete decisions: to put a certain type of line in a certain place because that’s what I want to do.

Kauffman: How do these approaches to gesture and decision-making translate in a residency? Does the residency experience amplify the opportunity to create these edges or boundaries to how you will approach or begin something?

Breuer: One of the dangers of having a good studio set-up is that it can create ruts. You know how things work, you know your materials, you know your tools, and it becomes tempting to stay in these ruts. A residency is an opportunity to shake it up and to embrace the limitations. Here, I don’t have the ruler that I like to work with, and that’s annoying for two days—and then I realize that the ruler I have here has something to it that I wouldn’t have discovered otherwise. There is an opportunity to reset, and to approach the residency not only as your studio in a different location, but also as a different mental framework. It’s a chance to not just take the show on the road, but to work with a new configuration.

Marco Breuer’s studio during his 2016 residency at Headlands Center for the Arts (artwork © Marco Breuer; photograph by Andria Lo provided by Headlands Center for the Arts)

Kauffman: Many artists-in-residence at Headlands talk about how contextually laden the space itself is and how the residues of its various histories are still felt and influence the work. Have you felt that influence?

Breuer: I tend not to engage with things that concretely, so the fact that Headlands was once a military base doesn’t directly trickle into my work. It’s more about being in this room, and seeing how things happen differently here. It’s the small stuff that changes: the height of my worktable changes the pressure of the tool interacting with the paper, which produces a different line. The challenge is to be flexible and to embrace unfamiliarity—to not see it as a limitation or as the “wrong” set-up, but instead as a different set-up. Once you can embrace that, there’s opportunity for discoveries that you wouldn’t have made otherwise.

Kauffman: Are these things—like the inclination to simply change the height of your table—ideas that you’ve tried to bring home into your practice after experiencing the effectiveness this flexibility brings to your work?

Breuer: I intentionally keep a makeshift setup in my studio. I do this partially because the setup changes depending on the project I’m working on, so it needs to be flexible. I don’t have a great studio and I’ve never had a great studio. Part of me wants one, and part of me is afraid that that would be the death of my practice. Once you have that “perfect” setup, then why keep going? However, I have learned from being elsewhere. I’ve taken ideas home. I went to the MacDowell Colony, which has great studios, and I loved that there’s no internet in their studios. If you need to go online there, you walk to the library. The internet is not part of the day there, and it leads to a different degree of focus. You can learn so much from these different working situations.

Kauffman: How have the communal aspects of residencies been for you?

A visitor in Marco Breuer’s studio during the Spring 2016 Open House at Headlands Center for the Arts (artwork © Marco Breuer; photograph by Andria Lo, provided Headlands Center for the Arts)

Breuer: Being here is an opportunity to spend time with painters, sculptors, musicians, and writers, and to ask questions about their work and their process—having conversations in this extended timeframe. Outside a residency you might talk to a musician in a social context, but this is different. I used to teach in the Bard MFA program, which is interdisciplinary, and that was one of the other places where I had this experience.

I tend to hang out with the writers during residencies. If you’re going to hang out with people, you’re going to talk, and writers know how to talk, generally. I’ve met some people here I hope to work with in the future. I’ve worked with a number of writers over the years who I met at MacDowell. I was working on SMTWTFS (2002) at MacDowell, and I asked a number of artists to respond to my work. I invited them to the studio and asked them to contribute something that I could print in a reader for the back of the book. Lynne Tillman wrote one of her “Madame Realism” pieces and the musician Evan Hause wrote compositions based on the work. The idea was to escape the standard art historian’s catalogue essay—this voice of authority that gets to say what the work is about. I wanted to emphasize the idea that any response is a subjective response, and that there doesn’t need to be a hierarchy—a musician’s response is equally valid to a writer’s or poet’s.

Kauffman: How do you balance the different aspects of having your own practice, working closely with a gallery, teaching, and participating in residencies?

Marco Breuer, Untitled (Cleaner), 1999, silver gelatin paper, exposed, unique, 11 x 8-1/2 in (27.9 x 21.5 cm.) (artwork © Marco Breuer; provided by the artist and Yossi Milo Gallery)

Breuer: I don’t teach anymore. At some point I wasn’t into it anymore, and it is a difficult job if you don’t love it. I see a lot of my friends, artists who teach, tied up in administrative work, so I’m happy to not have to do that. Living remotely in the country and working by myself, means that a residency is the place for me to have extended conversations with people in other fields. These conversations don’t happen within the gallery framework, when everyone is focused on specific goals. A residency becomes the place where I can have conversations that go deeper.

When I lived in Manhattan, residencies were also a way to get out of the city. Those needs have obviously gone now that I live where I do, so it’s more about the opportunity to work with other artists, or in the case of Headlands, an opportunity to work with people in San Francisco—to meet with artists, book designers, and gallerists. I connect with someone here almost daily, and that would be difficult to do from my home.

Kauffman: Do you enter into residencies with a certain expectation of what would make for a productive time?

Breuer: When I was at MacDowell Colony the first time, I went with a deadline and a concrete project that I needed to finish. I ran into technical problems, and it didn’t work out, which was frustrating. When I returned for another residency, I set up differently. I brought materials and tools but not a concrete project, and decided to see what would happen. It was actually a good, productive stay. That’s the challenge: to be open, but to prepare and have materials ready. With this residency, it’s a combination. There is work I should finish here, and I am also playing around generating many dead ends. I do always try to bring things to some level of completion, even if it’s just a box of tests. Work can look different ten years later, or reveal a related process, which becomes the answer to other questions. You can’t always tell when you’re knee-deep in it, so I try to have documentation that I can return to and connect with something in the future.

Marco Breuer, Untitled (E-33), 2005, cyanotype on Fabriano paper, unique, 15-11/16 x 12-3/8 in (39.8 x 31.4 cm.) (artwork © Marco Breuer; provided by the artist and Yossi Milo Gallery)

Kauffman: You’ve talked a lot about collaborations with writers. Is language an important aspect of your work, or an entry point into it, for you?

Breuer: As an artist, you write about your work on a regular basis, and you work on press releases and other texts, so language is a necessary crutch. But it’s certainly not how I get into the work. I do have a complicated relationship with language because English is not my first language. Halfway through my life I switched from German to English, which has changed things. There are different cultural concepts that can be expressed in certain languages, and you quickly become aware of them when you start speaking another language. At this point, I can barely talk about my work in German anymore because I don’t have the conceptual vocabulary—I developed it in English. I speak German, just not that particular slice of it.

Marco Breuer, Untitled (C-1485), 2014, chromogenic paper, folded/burned/scraped, unique, 19-15/16 x 16-13/16 in (50.6 x 42.7 cm) (artwork © Marco Breuer; provided by the artist and Yossi Milo Gallery)

Kauffman: The experience of the work can too easily become about the words and the description of it. Your work has a visual vernacular, but that vernacular is elusive in a delightful way—you see the impulses of a language, but there is not a particular semiotics.

Breuer: Every time you do attach words to artwork, you limit it. Obviously when visual work is written about, everyone’s looking for a hook—one sentence that describes what the work is about. I’ve always thought that’s a problem. If you can describe someone’s work in one sentence, there’s not enough happening. I try to point this out when I talk about the work. I make it clear that the verbal discussion is a secondary stage, and what we should be doing is looking at the work. When reproductions are involved—whether they are projections, slides, or reproductions in a book—there is loss in that translation too. I try to play this up, rather than pretend it’s not there. The ideal scenario is somebody encountering your work without preconceived notions in the original piece, seeing all the surface violations and the actual marks on the paper. The reality is that much of the work is consumed online, encountered either in some dematerialized form, or described in words, and none of these ways are ideal.

I gave a lecture at California College of the Arts on April 21, 2016, and the question of language is a big question I consider every time I speak. My work is not based in language, but I prepare to talk about my work for an hour. Lectures are also an opportunity to think about different aspects of your. I built this lecture in five different loops. The reason that I chose the loop is that I don’t believe in linear progression—I always return to things I’ve done before, or some variation of them. There’s a circular element in the forward motion of everything.

Vanessa Kauffman is a writer based in Oakland, California. She has an MA in visual and critical studies, and a BFA in printmaking. Her writing—which focuses on contemporary art, poetics, textiles, and print culture—has appeared in Art Practical, Sightlines Journal, andreview, and Eleven Eleven. She is the communications and outreach manager at Headlands Center for the Arts, a multidisciplinary, international residency center in the Marin Headlands.

Marco Breuer has had solo museum exhibitions at the de Young Museum, San Francisco; the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; and the MIT List Visual Art Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts. His work has been included in group exhibitions at the Morgan Library and Museum, New York;, International Center of Photography, New York; the Drawing Center, New York; and White Columns, New York; Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas; and High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia. His work is in numerous public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.; J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and Staatsgalerie , Stuttgart, Germany. Breuer is the recipient of the inaugural Larry Sultan Photography Award (2015) and a Guggenheim Fellowship (2006). Monographs of Marco Breuer’s work include Col•or (London: Black Dog, 2015), Early Recordings (New York: Aperture, 2007), and SMTWTFS (New Yokr: Roth Horowitz, 2002). Breuer has taught photography at New York’s School of Visual Arts, and in the MFA program at Bard College. A traveling retrospective of Breuer’s work will open at the Milwaukee Art Museum in 2018.