Joel Tauber, still from Happyville, 2015, video, 11 min., 31 sec., part of The Sharing Project installation (artwork © Joel Tauber)

One of the most interesting characteristics of the contemporary art scene is its capacity to bring together people with completely different backgrounds and personal stories. I was introduced to Joel Tauber and his practice at a gallery opening on a sunny afternoon last year in Los Angeles. Within a few seconds of talking, we discovered our mutual admiration for Bas Jan Ader, a Dutch artist who made his career in California in the 1960s and 1970s. Joel told me about his work Searching for the Impossible: The Flying Project (2001–3), which was inspired by Ader’s infamous “falling” pieces; and I told him about my current research project on Ader for an upcoming book.

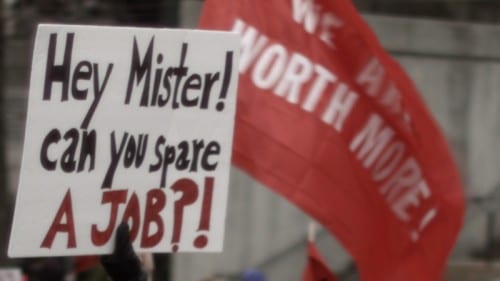

A few months after this first encounter, Joel invited me to discuss his most recent work, The Sharing Project (2012–16). It is based on America’s socialist and leftist movements during the early twentieth century and how these movements—after the Second World War and McCarthyism—largely disappeared from our collective memory.The Sharing Project strongly connects to this vanished past, and has been constructed to be distributed through a multiplicity of formats and media: film, installation, texts, and public art. This versatility is related to its content: a reflection “about whether we share enough in our capitalist world” 1. The project’s point of reference is the socialist Jewish community of Happyville—a utopian settlement built in the woods of South Carolina, close to where Tauber now lives and teaches at Wake Forest University, in North Carolina. Alongside his research about Happyville—established in 1905 and abandoned in 1908—the artist conducted interviews with experts in different fields about the meaning and value of sharing. In addition to this academic approach, he worked poetically by trying to symbolically dig up Happyville’s mysteries and secrets with his young son Zeke, in a process both artistic and pedagogical.

The subjects of The Sharing Project are some of the most urgent social, political, and economic issues of our time: the division of wealth, goods, and natural resources; neglected stories of radicalism in America; and the growing influence of mercantilism in the art world.

Our conversation took place over e-mail in April and May 2016.

—Pedro de Llano

Joel Tauber, Attempting to Restore Happyville, 2013, photograph, part of The Sharing Project (artwork © Joel Tauber)

Pedro de Llano: Happyville was established before the similar community of Llano del Río in Llano, California (not far from Los Angeles, where we met and you went to graduate school), which existed between 1914 and 1918. How did you discover Happyville? Did you find any connections between Happyville and Llano del Río or other socialist or leftist communities?

Joel Tauber: I lived on a kibbutz for a summer when I was eighteen, and the experience made a lasting impression on me. As part of my exploration into the meaning and value of sharing, I started investigating the histories of kibbutzim and other socialist communities. In the middle of an anthology about old communes, I stumbled across a one paragraph description of Happyville and was immediately captivated. I sensed that the Happyville settlers could teach me about sharing in ways that no one else could. I had already followed their path as a fellow Jew, migrating as they did from the big city to the Carolinas. I hoped I could become inspired to follow their lead in other ways, too. This hope for guidance was tempered by an awareness that the commune had disappeared long ago, and that the settlers had all passed away. Little had been written about Happyville, and it was not clear where the 2,200-acre site was precisely located.

Eventually, some of Happyville’s mysteries began to reveal themselves. I read all the primary and secondary documents that I could find, and I interviewed a Happyville descendent, Marcia Savin. Marcia put me in touch with a docent at the Aiken County Historical Museum in South Carolina, Doris Baumgaurten, who gave me a copy of an old map that included Happyville on it. Then, with the wonderful help of our friend Gary Hooper, we were able to determine the exact location (near Aiken, SC) that was marked on the map. I contacted the owner of the property, who did not know about the existence of the commune—this wasn’t surprising because almost no one else had heard of it—but was kind enough to allow me to search and film on the site.

It’s been thrilling to explore the place where Happyville once existed. The dam built by the settlers is still in great shape, and the lake that was a critical resource for them is still there, but I have not seen any signs of the saw mill, water turbine, or cotton gin that they built. A large, old house, falling apart and occupied by some extremely large birds, retains a powerful, even haunting, presence on the land. Several smaller structures and old tools remain, decaying and disappearing into the landscape. I don’t know for sure if any of those buildings and tools were used by the Happyville settlers, but there’s a good chance that they were. As I contemplate them and the landscape, I can easily imagine what life might have been like for the settlers as they grew crops, raised livestock, and operated their sawmill and cotton gin.

Joel Tauber, still from Prized Tripods, 2015, video, 4 min., 10 sec., part of The Sharing Project (artwork © Joel Tauber)

The Happyville pioneers had plenty in common—as well as plenty of differences—with those who settled in Llano del Río. They were both part of a larger, mostly forgotten movement of socialist experiments in the United States, and they were both committed to sharing their resources in egalitarian ways. This meant different things in the two communities, because there were distinct cultural, religious, and economic elements in play.

The people who formed Happyville were poor, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe (mostly from Russia). They were intellectuals and atheists, and didn’t know how to farm before they arrived in Happyville. They came from the tenements in New York, where they worked long and difficult hours in the factories. They didn’t have the same financial resources or public visibility of Llano del Río, which was formed by Job Herriman (a former candidate for governor of California), and publicized in The Western Comrade magazine.

Unfortunately, both Happyville and Llano del Río didn’t last long. Some of the reasons were similar: they both faced environmental challenges and the inability to sell enough of their goods to sustain their communities. Some of the residents from the much larger community of Llano del Río migrated to Louisiana afterwards to create a new commune, while the Happyville (proto) kibbutzniks had to return to the tenements of New York.

Joel Tauber, still from Private Property and Inequity, 2015, video, 5 min., 27 sec., part of The Sharing Project (artwork © Joel Tauber)

De Llano: Why did they call it Happyville?

Tauber: It’s unlikely that the Yiddish-speaking settlers came up with that name. Life wasn’t exactly perfect or easy on the commune, despite being infinitely better than the factories and tenements of New York. The name Happville was probably coined by the State of South Carolina. It appeared in contemporary newspapers and in glowing government reports. South Carolina was interested in celebrating the successes of the commune, partly because it was truly an incredible feat, and partly because it was—in certain ways—a state initiative from the outset. South Carolina wanted to recruit “European” immigrants (i.e., white people) to farm some of its land, so it was in the state’s best interest to highlight the happiness and success of the settlers.

De Llano: Was Happyville an open community? Who could be part of it, and on what grounds?

Tauber: I don’t think there was a rush for people to settle there. The land was less than ideal: it was difficult to grow anything on the sandy soil. The fact that South Carolina seemed to be happy that Yankees—Jewish radicals, to boot!—wanted to live there says a lot.

I doubt that there was any official rule within the Happyville community that members had to be white—unlike Llano del Río, where being white was an initial requirement—or Jewish, but I also think that it was unlikely that anyone outside their particular social, cultural, and ethnic group of Yiddish-speaking, socialist intellectuals from Eastern Europe (via New York) would have felt comfortable joining them.

Joel Tauber, Trying to Fix Happyville, 2013, photograph, part of The Sharing Project (artwork © Joel Tauber)

De Llano: Could you elaborate on the role of religion in Happyville? There is a strong link between Jewish intellectuals and socialism since the nineteenth century, both in Europe and America. How did this relation coexist in Happyville?

Tauber: The Happyville settlers were intellectuals and atheists. They built a library, but they would never have imagined building a synagogue. They were interested in creating a new life for themselves—a life that was radically different from the ghettos of Eastern Europe that they had left behind. For the most part, Jews living in Europe at that time weren’t allowed to own land and thus didn’t have the opportunity to farm. They also often faced the threat of additional layers of terrifying persecution. It’s not surprising that there was a movement of Jewish intellectuals who dreamt of having different relationships to land and to property. Karl Marx, a Prussian Jew, is certainly one of those dreamers, and so were the Jews who started the kibbutz movement.

It must have been profoundly exciting—ethically and spiritually fulfilling—for the Happyville pioneers to learn how to farm on land that they collectively owned, and it must have been crushing to abandon their dreams and return to the tenements of New York after only three years. This must have been especially heartrending if the failure of Happyville was to a certain extent due to discriminatory acts of their neighbors—as Marcia Savin’s ancestors believed.

De Llano: You use archeology in this project: mining events that are not so old, yet have been buried under the deepest layers of our collective memory for political and ideological reasons. While researching Clement Greenberg and his milieu in New York during the 1930s, I discovered heated debates on leftist ideas. I found these debates suggestive in the context of my own European background. Outside the United States, people tend to think that the country is only about capitalism and Donald Trump. Looking back at history, we discover that this is not true, and that things could have been different. What is odd to me is that these stories are not clearly present in the public discourse in the United States.

Joel Tauber, What Mysteries of Sharing Are Hidden in Happyville?, 2013, photograph, part of The Sharing Project (artwork © Joel Tauber)

Tauber: The many American socialist experiments, like the one in Happyville, have not been as big a part of the public discourse in the United States and elsewhere as they should be, despite the current, heightened attention to socialist ideologies generated during Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign. I’m convinced that these stories have been buried for political and ideological reasons, as you state, because they encourage a reexamination of current political and economic “norms.” My hope is that The Sharing Project will help us recall these stories, generating discourse about our forgotten past and enabling us to imagine alternative futures.

De Llano: Why did you decide to investigate sharing in an interdisciplinary way, instead of focusing exclusively on political theory—and Marxism, for example?

Tauber: The question of how much we should share is interconnected with the question of what political system we should adopt. Inequity is not just a political problem—it’s also an ethical, philosophical, historical, economic, biological (perhaps), psychological, and pedagogical one. I’ve tried to expose the complexities of this problem through a rigorous, personal, and interdisciplinary examination of what is inseparable from any possible solution—the meaning and value of sharing.

Joel Tauber, 21 interviews: Adrian Bardon, Alex Rosenberg, Brenda Herman, Christian Miller, Colleen Lerner, Daisy Rodriguez, David Coates, David Graeber, Derwin L. Montgomery, Gene R. Nichol, Geoffrey Sayre McCord, Hayes McNeill, James Otteson, Jeffrey Faullin, Jennifer Knudson, Jessica Sommerville, Joseph Milner, Lynn Pritchard, Marcia Savin, Michele Gillespie, Win-chiat Lee, 2015, composite of video stills from twenty-one interviews, part of The Sharing Project (artwork © Joel Tauber)

De Llano: Some would argue that an egalitarian society can only be achieved through revolution: there has to be violence first, and the establishment needs to be overcome, as in the USSR, Cuba, and other utopian experiments. How should we navigate this conflict between good will and struggle? Is it unavoidable? Did any of the experts that you interviewed discuss it?

Tauber: I don’t think that change must happen through revolution or violence. There has been a lot of progress (and plenty of setbacks) in many different arenas—feminism, gay rights, the green/environmental movement, public health (smoking…)—that have happened by changing the cultural landscape through art, and other methodologies of discourse.

That said, I think the tension you describe between altruism and good will on the one hand, and selfishness and violence on the other may be unavoidable. Alex Rosenberg, the philosopher of science, told me that humans have conflicting genetic impulses: some encourage us to be selfish, and others encourage us to act altruistically. Other experts described similar kinds of conflicts, internal and external, that manifest in psychology, anthropology, and politics.

Joel Tauber, The Sharing Project, installation, University Art Museum, California State Long Beach, 2015 (artwork © Joel Tauber)

De Llano: How do you think sharing effects the art world, especially in a moment when the private sector is so powerful?

Tauber: There are certainly components of the art world that have little to do with sharing, but things may be starting to change. I like the Artist Pension Trust for a number of reasons, but mostly because it incorporates sharing into its structure. When works of art invested in APT are sold, the artists in this large collective share much of the profits. I think this encourages artists to root for each other, which can only be a good thing.

De Llano: How is this project related to your previous ones?

Tauber: While my projects are different in many ways, they do share certain commonalities. They begin with rigorous research that is synthesized and presented in poetic, personal, and often humorous ways; they employ formal and structural choices that are deeply tied to their content; they raise questions about how to make sense of the other; and they wonder how to determine what our responsibilities are beyond ourselves.

Joel Tauber, SHARE, 2014, photograph, part of The Sharing Project (artwork © Joel Tauber; photograph direction Joel Tauber; shot by Kristi Chan)

De Llano: How does an artist get to the idea of working with his 2-year-old son on a project? Do you know of other artists who did something similar?

Tauber: My exploration of sharing has been intertwined with Zeke’s. I felt that it made sense to highlight his thoughts and experiences alongside my own. There’s a long history of artists (including Rembrandt and Seurat) who made work featuring members of their family. One who continues to inspire me deeply is Guy Ben Ner.

Joel Tauber, The Sharing Project, installation, University Art Museum, California State Long Beach, 2015 (artwork © Joel Tauber)

De Llano: The project incorporates the idea of sharing into its own structure. How does this work do so, and how does it relate to a tradition of projects in which sharing is important—for example, the works of Rirkrit Tiravanija and Félix González-Torres?

Tauber: As part of the installation, audiences are invited to share their toys and help arrange them in the gallery or museum over the course of the exhibition. The growing mound of toys becomes emblematic of both generosity and excess. At the end of the show, the public is invited to take the toys and give them away to whomever they think will enjoy them, furthering the actions of sharing.

There are strong connections between this communal sculpture and Félix González-Torres’s candy piles, but also important differences regarding both the creation (which is a communal act) and dissipation (which requires giving, not just taking) of the toy sculpture. I think there are also interesting connections to other artists—like Rirkrit and the Cuban artist Adonis Flores—that create platforms where sharing occurs in different ways than it does normally.

De Llano: How do the art installation and the videos relate to each other?

Joel Tauber, The Sharing Project, installation, University Art Museum, California State Long Beach, 2015 (artwork © Joel Tauber)

Tauber: The installation features fifteen short films and twenty-one interviews. The foreground video, presented on the largest screen, tells the story of Happyville; while the camera slowly contemplates the site where Happville once existed. Zeke and I wonder aloud if some of the mysteries of sharing are buried in the traces of the forgotten commune. Determined to uncover them and “fix” (metaphysically and poetically) whatever caused this utopian community to disintegrate, we get to work with Zeke’s special tools: probing, digging, and “fixing” an ancient tractor and a decaying building.

The other fourteen short films operate as a dialogue between Zeke and me. On seven screens, the camera examines Zeke’s toys and my gear, as I talk about the complexities of sharing in a personal and interdisciplinary way. Seven more screens focus on Zeke—and me—grappling with the challenges of sharing. A tablet in the installation features twenty-one experts in different fields offering their thoughts. As a feature film, The Sharing Project will weave together Zeke’s and my struggles to understand the meaning of sharing, ideas from experts in different fields, the current battles in North Carolina over inequity, and the Happyville story.

Joel Tauber is an artist and filmmaker (BA: Yale; MFA: Art Center College of Design) who teaches experimental film and orchestrates the video art program at Wake Forest University. He has held solo art exhibitions at venues including Galerie Adamski in Berlin and Aachen, Germany; University Art Museum at California State Long Beach; Helen Lindhurst Fine Arts Gallery at the University of Southern California; Rocky Mountain School of Photography, Missoula, Montana; and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Tauber’s work has been included in numerous group art exhibitions such as the 2004 and 2008 California Biennials at the Orange County Museum of Art and The Gravity in Art at the De Appel Arts Centre, Amsterdam. Film Festivals include the Sedona International Film Festival and the Downtown Film Festival Los Angeles, where his movie, Sick-Amour (2010), was awarded “Best Green Film” in 2010. Tauber is the recipient of the 2007 Contemporary Collectors of Orange County Fellowship, the 2007–2008 CalArts/Alpert Ucross Residency Prize for Visual Arts, and a 2015 grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation in conjunction with a residency at Grand Central Art Center. Sick-Amour was shortlisted for a 2011 International Green Award.

Pedro de Llano is an art historian and curator. His writings have been published in art magazines such as Exit Express (Madrid), Carta (Madrid), Afterall Online (London), Springerin (Wien), and Texte zur Kunst (Berlin), and in newspapers including La Vanguardia (Barcelona). He has written texts about artists John Knight (2013), Stephen Prina (Afterall Online, 2009), Mauro Cerqueira (Caldeireiros, 2012), and Daniel Steegmann (Texte zur Kunst, 2013), among others. He curated the exhibitions In Search of the Miraculous: Thirty Years Later, focused on Bas Jan Ader´s posthumous project, at the Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea (CGAC) in Santiago de Compostela (2010); The Black Whale (MARCO de Vigo, 2012); and the first retrospective of Maria Thereza Alves at the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Sevilla (2015). He is currently editing a book on Bas Jan Ader that will consist of a collection of documentary materials and oral records, including unpublished writings by the artist, writings about him, and previously unpublished early art works.

- Joel Tauber, The Sharing Project website, https://thesharingproject.net/about, as of 9/14/16. ↩