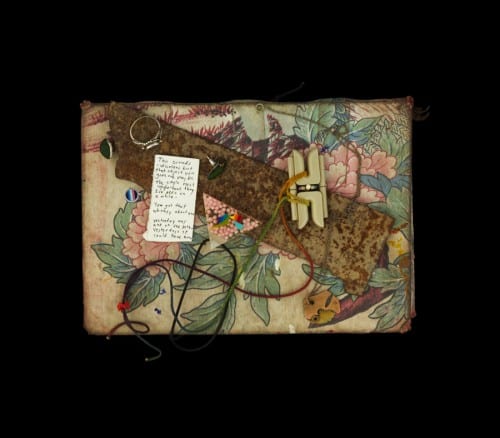

Kija Lucas, Flora, 20, Reading, PA, 2015, photograph, from Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment (artwork © Kija Lucas)

I first met Kija Lucas in 2005, when she was attending the San Francisco Art Institute and I was a recent East Coast transplant moving into a studio at Root Division, a small grass-roots arts organization in San Francisco’s Mission District. Twelve years later, we have known each other through multiple apartments, advanced degrees, and artist studios in San Francisco, including Lucas’s own studio artist residency at Root Division in 2010. Our lives continued to overlap at Root Division when I was hired in 2011 to run the Exhibitions Program, and Lucas was also on staff managing the education programs.

Root Division is visual arts non-profit that runs four interconnected programs, the core of which is the Studio Program. Selected artists receive a studio, paying half of market rate value for the space and access to the facilities and networks. In exchange, artists volunteer their time in the other three programs: Youth Education, Adult Education, and Exhibitions. In the Youth Education Program, Root Division trains and places teaching artists in after-school programs working with underserved populations. The Adult Education Program features courses developed by our artists taught onsite at Root Division, in areas from painting and drawing to grant writing and portfolio reviews. The Exhibitions Program features twelve monthly exhibitions in our gallery space, and artists in the Studio Program assist in installation, staffing, and event production. Root Division is an incubator program where the artists volunteer their time while gaining valuable professional experience.

In 2013, Lucas left Root Division to pursue her photographic practice full-time, setting out on a self-guided and crowd-funded road trip across the United States, tracing her personal heritage as a mixed-race woman through documentation of flora at sites of importance for her family in a project called In Search of Home (2013–present). She often refers to this trip as her “first residency,” although it was entirely self-directed. After receiving many stories and family artifacts at each site, Lucas became interested in how objects define our personal histories and the social interaction of photographing significant personal objects. Both are center to her project, Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment (2014–present), an encyclopedic archive based on her travel and community engagement. For the entire year of 2015, Lucas traveled across the United States between residencies to develop In Search of Home and Objects to Remember You By, asking local community members to bring objects and stories to her studio or public sites so she could document them.

Our conversation addresses how residencies have shaped her artistic practice and her inquiry into memory, object, and place. Lucas discusses her community-based practice, her experiences in residencies across the US (including Wassaic Artist Residency, Wassaic, New York; Grin City Collective, Grinnell, Iowa; Montalvo Art Center, Saratoga, California; and Bunker Projects, Pittsburg, Pennsylvania), and her upcoming plans for Bay Area residencies at the De Young Museum and Growlery (both located in San Francisco). And we discuss the evolution Root Division’s programs, including its resilience during a forced relocation amid San Francisco’s challenging economic climate. The success of the organization’s growth in the face of adversity mirrors the survival strategies of its current Studio Artists and alumni.

—Amy Cancelmo

Kija Lucas, Jenny, 38, San Francisco, CA/Brooklyn, NY, 2014, photograph, from Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment (artwork © Kija Lucas)

Amy Cancelmo: It’s great to have you back in the Bay Area.

Kija Lucas: I am excited to be back. This isn’t the easiest place to be an artist, but there is a dynamic community of people who are committed to making this place work.

Cancelmo: Your relationship to residencies and travel is interesting for me in dialogue with your work, which is about tracing lineage and documenting the objects that define home. Do you see these things in conversation in your life and in your practice?

Lucas: Travel and residencies pared down my life, and this has made me more curious about what others collect and hold on to. I have always been interested in stories, how other people live their lives, and the lenses through which they see the world. This lifestyle has made me more comfortable asking deeper questions of people I don’t know well. Not having the distractions of daily life or friends and family near to discuss the day has forced me to get comfortable with strangers in a way I never had been.

Cancelmo: It’s such a brave thing to do, to abandon the home base and travel where the work takes you. What made you take the leap?

Kija Lucas, Raphael, 50, San Francisco, CA, 2015, photograph, from Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment (artwork © Kija Lucas)

Lucas: I’m quiet, and my artwork is kind of quiet, and I felt like I had to figure out a way to make my work and put it out in the world. That’s also why I first applied for a studio at Root Division back in 2010. When I was leaving grad school I was afraid to work in a vacuum. I would go into my studio and work, but I felt no one outside my studio would ever know what I was doing. I knew I could do the work in radio silence, but Root Division gave me community and opportunities.

Cancelmo: Ultimately, the practice you developed has forced you to push outside the Bay Area and engage with other communities.

Lucas: It had to do with the support of Bay Area organizations as well. I was offered an opportunity to work with ProArts in Oakland to propose a project in its front window. I also did one day of shooting at Root Division and a weekend at Incline Gallery in San Francisco, which helped me to get the project rolling. I was pleased and surprised at how many strangers and walk-ins decided to participate. I began to trust the project and my process. My residency at Wassaic Project was the first time that I was working on the project as a full-time job.

Cancelmo: How long were you at Wassaic?

Kija Lucas, Vitrine 1, 2015, photograph, 24 x 28 in. (60.9 x 71.1 cm), from Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment (artwork © Kija Lucas)

Lucas: I was there for three months, which was perfect. Because it was such a small place, I needed that much time to develop the trust for people to participate. I spent four nights a week sitting at a bar with my studio setup. I would talk to people about the project and get them to bring stuff back, or sometimes people would have the sentimental things with them already and we would shoot them then and there. I embedded myself there: I would work from three in the afternoon to eleven at night, until they closed the bar, and just photograph objects. Sometimes two people would come, sometimes ten or fifteen people.

Cancelmo: There’s this interesting catharsis to what you’re doing for people—it’s an intimate experience, to share sentimental objects and stories. I imagine some people are resistant at first because it’s a “weird art project” from a visiting artist, but then actually it becomes this personal interaction, a nostalgic confessional.

Lucas: It’s funny because nostalgia is often a totally taboo thing in art, and at first that was something I was nervous about. But my work has always had to do with the things that we are trying to remember but can’t quite hold on to.

Cancelmo: It’s one of the things that photography can do so well: hold something and freeze it in time. As a photographer and someone who is working with social practice, you are creating that space for this kind of nostalgia and personal history, and recording it for posterity.

Lucas: It’s an incredible gift to be able to hold that, and to know all these different people’s stories. The objects I’m photographing have their own aura. They have a lifetime or more of history, so to have people share that with me is amazing, and I have to be respectful. Photographing the work is not only physically exhausting from moving the studio around for each image, but also emotionally—it can be a lot to hold.

Cancelmo: And you’re holding it all online. The archive you are building lists the first name, age, and location of the object’s owner and information about that object. In a way, it’s an anthropological reference point, marking what is important to them at this time in their lives.

Kija Lucas, Sara, 23, Los Angeles, CA, 2014, photograph, from Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment (artwork © Kija Lucas)

Lucas: I don’t want people to bring the object that they think looks the coolest—I want them to bring the object that’s the most important. There are so many institutions that collect objects considered to be monetarily or historically important. My interest is in asking people who are not necessarily part of that decision-making canon to contribute the objects that are personally valuable.

Cancelmo: During these residencies you are living and working alongside other artists, and many of them have participated in your project. Can you tell me a little about some of the people you’ve met along the way? Did you notice any trends in who was attending residencies?

Lucas: Every artist I met was in a different space. Some were international artists coming to the United States for a month or six months to make work, some were on the same hustle I am in trying to find a way to be a full-time artist, some were already full-time artists, some were just taking time off from their jobs and lives to make work, so I can’t say there’s really a trend—but I can say it’s been incredible.

When I was in Grinnell at Grin City Collective, I lived in a house with writer Maggie Messitt, who was writing her doctoral thesis about her aunt who disappeared, using objects from her life. She asked me to photograph some of the objects while we were there, and I ultimately ended up applying to the Bunker Projects residency so that we could potentially be in the same city working on that project together. I spent three months there working on my own project, and photographing the objects she was writing about for her book. She’s a really amazing writer and our work was so parallel and in sync.

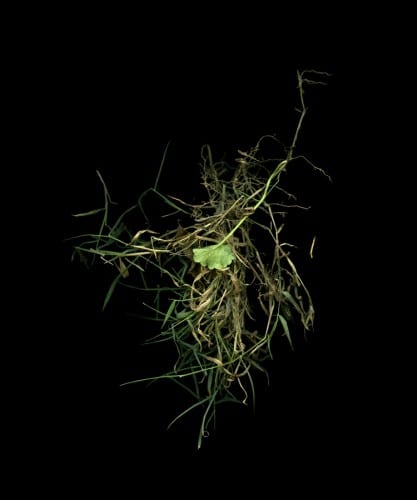

Kija Lucas, Bristol 30, 2013, archival pigment print, 20 x 24 in. (50.8 x 60.9 cm), from In Search of Home, (artwork © Kija Lucas)

Cancelmo: There’s this joke in the Bay Area that if you want to get a job teaching, or succeed as an artist here, you have to leave and then come back. Have you found that to be true? As if leaving the nest is a rite of passage in the career of an artist?

Lucas: I do think I got to show a bit more when I came back. It seemed like people were more interested, but it’s different for every artist. For people who are interested in a residency, or even applying to be in shows, you have to make sure it makes sense for your work. The social part is great too, but the biggest part of it is being able to be an artist full-time. That’s why I did it—to be a full-time artist and not have to hustle eight jobs in San Francisco. I have a friend who told me to apply to five things a month, so I started doing that. One thing led to another, and somehow it fell into place.

Cancelmo: It seems like foregoing capitalism, or living off the grid—as if you have found a way to exist as an artist outside of “side jobs” or “the hustle.”

Kija Lucas, Grinnell 222, 2015, archival pigment print, 20 x 24 in. (50.8 x 60.9 cm), from In Search of Home (artwork © Kija Lucas)

Lucas: Aside from my residency at Montalvo, I had to pay a small fee at all of the residencies I went to, but for me it was cheaper than paying rent on an apartment and studio in San Francisco. Because of the nature of my specific project, it made sense to invest in the travel. Most residencies have scholarships and a lot have work trade. Wassaic has a teaching scholarship, but I decided not to apply because I wanted to focus on my work rather than teaching.

At Grin City, I specifically applied to do the gardening work exchange on the organic farm I was living on because it made sense for the work I was doing there. Grinnell was one of the only places where I was able to work on two projects at once: Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment, and In Search of Home, a project that ties the emigration patterns of my family to the racial taxonomy of Carl Linnaeus through scans of plant clippings, rocks, and other objects from sites significant to my family history. The location of that residency was really why I pursued it, and the ability to work on a farm that was twenty minutes from where my great-great-grandparents had farmed, in a town where three generations of that part of my family had lived. I was able to meet my 102-year-old cousin there, which was incredible. I felt that my ancestors were actually working that land. And the work exchange there paid for half of my residency.

Cancelmo: The give/get model is interesting. It seems like the opportunity is there for it to be both a work trade and a form of professional development. It reminds me of Root Division’s model, which is nonresidential, but has a similar application and review process. Our studio space is subsidized below market rent in exchange for artists volunteering their time teaching in our adult or youth education programs, or helping with the exhibitions program.

Lucas: In our working society, often time equals money; in making art, not so much. With a space like Root Division, and many of the residencies I’ve been on, you put in some money and time—you’re not giving all of one or the other. There are very few people who are going to be involved in a system that is showing and selling their work enough in order for them to get paid for it, especially straight out of school. Root Division helps you get those supplemental skills that most of the schools don’t teach. It also teaches you to do a little bit of a hustle.

It’s important that spaces like that exist, because studios are expensive. I can’t afford one now that I’m back in San Francisco. I’m a studio photographer, but luckily my studio can be wherever I take my equipment—it fits in my trunk, or I’ll take it on a plane with me, or I might be at the library—but I do like to have an actual place where I only work because it is distracting when you’re working on the kitchen table.

Cancelmo: Adaptability is key for artist survival. Your practice is completely set up for movement. Do you think in residencies will continue to be a part of your practice long-term?

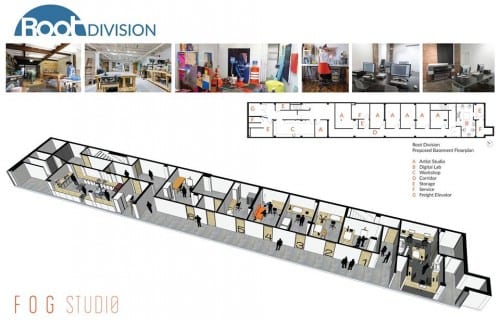

Root Division, San Francisco, California (photograph by Mido Lee Productions; photograph © Root Division)

Lucas: At the end of this year, I will continue working on several ongoing projects at a new residency called the Growlery in San Francisco. They have live, work, and exhibition spaces for artists. I will be at the De Young Artist’s studio for a month-long residency in 2017, working on Objects to Remember You By. I am excited to be able to work with museumgoers, photographing their sentimental objects to be displayed in a way similar to the way the work is shown in the museum. I’m also interested in traveling to do some short-term projects in different spaces.

Cancelmo: It’s exciting there are many of new opportunities for residencies in the Bay Area—residencies at the David Ireland House at Capp St. start next year, there’s the Minnesota Street Project, and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is doing more programming with contemporary artists.

Lucas: Root Division is booming too. Seeing the Root Division transition over the past two years for afar has been really exciting. Can you talk a little about moving from the original Mission District location to the new mid-Market location?

The opening reception of RESONATE, Root Division, September 2015. This was Root Division’s inaugural exhibition after the organization’s 2015 relocation (photograph © Root Division)

Cancelmo: When we lost our home of ten years in 2014, it was terrifying on many levels. We were faced with one of the most aggressive rental markets in the country, but were determined to not have to leave the city, not to go dark nor even to go dim, and we wanted to make sure our artists had space to make their work as seamlessly as we could throughout the process. We operated from an interim location on Market Street for fourteen months during the transition, and there were only two months during the construction of our interim and long-term homes when we had to hold shows offsite instead of in our gallery. We maintained our exhibitions, education, and studios programming at full steam. We got lucky, and secured a long-term lease with a very supportive landlord for our new building, which we moved into in September 2015. We had a ton of community support.

Lucas: The new space is not only huge, but also feels less scrappy and like more of a grown-up organization. How do you think the transition has affected the nature of Root Division?

The proposed floor plan for Root Division’s lower level. The studios and woodshop opened on August 1, 2016. (image provided by Root Division)

Cancelmo: The organization has grown up a lot since the days when we were studio artists, but we are still serving the same constituencies, making space for emerging artists, and teaching classes to underserved youth in the community. Losing our old space was the best “worst thing” that could have happened for the organization. Our new space is almost twice the size of the original: it’s a standalone, three-story building with natural light, and even more room for artist studios, classes, and exhibitions. I think that our being scrappy is what helped make the transition possible—I see parallels here to how artists have to hustle, to survive in San Francisco. There’s a survival strategy for small arts- organizations, similar to what you describe in your own practice. I like to think that residencies and organizations like Root Division are helping to foster self-motivated mindset early in artists’ careers so that they are more likely to be successful as they continue. That’s a big part of what makes it possible to survive as an artist in San Francisco, or anywhere—the self direction and impetus to just take that first step, like you did.

Lucas: We continue to value activity and sustain our arts community through sheer will. And for now, I am glad to be back home, and to be a part of whatever it is we are doing here.

If you would like to host Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment in your community contact the artist directly at kija@kijalucas.com.

Amy Cancelmo is the art programs director for Root Division, where she annually oversees twelve exhibitions and accompanying public programs and publications, and works with over 350 artists. Cancelmo received her MA in queer art history from San Francisco State University in 2011 and a BFA in painting from Syracuse University in 2004. Her recent curatorial project Strange Bedfellows, a traveling exhibition and accompanying catalogue, explored collaborative practice in queer art-making. It was first presented in San Francisco as part of the National Queer Arts Festival in June of 2013, before touring five cities, including Chicago, where it was the sponsored exhibition of the Queer Caucus for the Arts at the College Art Association conference. She currently serves as the Treasurer for the Queer Caucus for the Arts.

Kija Lucas is an artist based in the San Francisco Bay Area. She uses photography to explore ideas of home, heritage, and inheritance, and is interested in how ideas are passed down and how seemingly inconsequential moments create changes that last generations. Lucas received her BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 2006 and her MFA from Mills College in 2010. Her work has been exhibited throughout the Bay Area at Headlands Center for the Arts, California Institute of Integral Studies, Altar Space, Intersection for the Arts, Luggage Store, Mission Cultural Center, Root Division, Bedford Gallery, Pro Arts, and Asian Resource Center Gallery. Other venues include Venice Arts in Los Angeles; La Sala d’Ercole/Hercules Hall in Bologna, Italy; and Casa Escorsa in Guadalajara, Mexico. Lucas has been an artist-in-residenc at The Lucas Artists Residency Program at Montalvo Center for the Arts in Saratoga, California; Bunker Projects in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Grin City Collective in Grinnell, Iowa; and Wassaic Artist Residency in Wassaic, New York.