Dore Ashton died on January 30, 2017.

Art critics and historians recognize her as one of the most energetic, widely published, and politicized American writers on art, and one of the chief proponents of the artists of the New York School (she decried the label Abstract Expressionism).

Dore’s familiars knew her as a great lover of literature, the visual arts, and an outspoken political activist. I was privileged to know her as a dear friend and a staunch colleague.

I am grateful for the time I was able to spend with Dore and her family, and especially appreciative that my daughter was also party to her remarkable recollections and able to profit from the example of such an extraordinary human being.

What follows are a few tokens of that friendship: images and memories that take on a new urgency, burnished by Dore’s passing.

Corresponding with Dore. Writing to Dore meant sitting down, actually writing a letter, and mailing it. No e-mail because she didn’t use a computer. Dore lived in another world where the act of composing one-half of an imagined conversation with a distant friend remained a sacred ritual unavailable to producers of e-mails, texts, or tweets.

If lighting up a cigarette, sitting down to the typewriter—drink in hand—and pounding on the keys are for many another country, then Dore’s joy will appear to be some anthropological curiosity deserving of preservation.

I don’t see it quite like that. I picture, instead, a holiday camp where people of a certain age are instructed in the mysteries of such lost arts. It would be like a heritage village, except without the ridiculous historically accurate costumes.

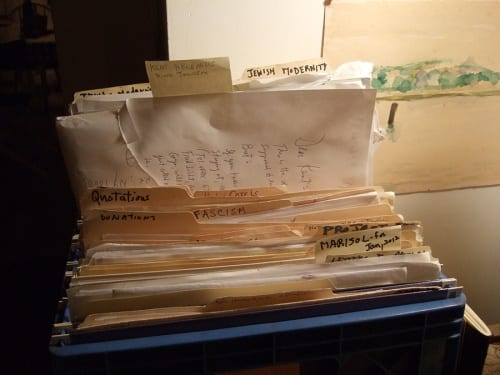

![“[Emily] Dickinson, A letter is a pleasure of the Earth—denied to the Gods + Baudelaire or Delacroix (?) speaks of ‘très belles heures de l’âme’.” (photograph © Madeline Djerejian)](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/3_DSCF0176-500x375.jpg)

“[Emily] Dickinson, A letter is a pleasure of the Earth—denied to the Gods + Baudelaire or Delacroix (?) speaks of ‘très belles heures de l’âme’.” (photograph © Madeline Djerejian)

Dore’s summer bolt-hole was a modest cottage in a prime location not far from that famous cemetery in Springs, Long Island, New York. We were always prepared to do some maintenance work, and that’s what we did: paint the porch, patch up the car, and change a few lightbulbs.

Dore Ashton’s desk at her home in Springs, Long Island, New York, summer 2011 (photograph © Madeline Djerejian)

Dore Ashton reading in her garden, Springs, Long Island, New York, summer 2011 (photograph © Madeline Djerejian)

Dore loved to talk about her work and the artists and writers she knew, but not necessarily about herself. Her mantra was “All freedom in every sense.” In conversation before audiences at the Meadows Museum and the Nasher Sculpture Center (2011), Dore said, “It has always been difficult for historians to fully grasp the intelligence of painters.”

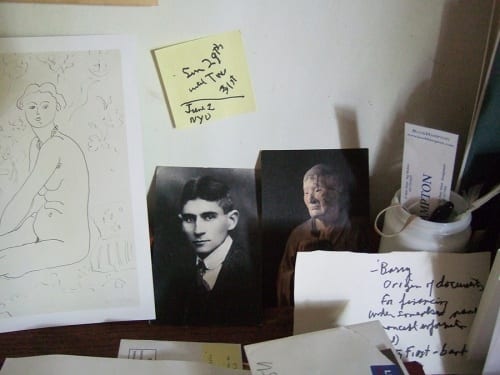

The salon, known to many as Dore’s home, on Eleventh Street. Dore’s house in New York City was filled with ghosts. Throughout her life she maintained close relationships with the artists and writers she commented on, among them Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Philip Guston, Franz Kline, Lee Krasner, Octavio Paz, Marcel Duchamp, Antoni Tàpies, and Isamu Noguchi. My daughter took this photo of Dore while sitting in a chair once graced by Alger Hiss. Dore’s house was haunted in this way, and she was the medium through which these spirits spoke.

Dore Ashton at the kitchen table in her home on East Eleventh Street, New York, New York, 2011 (photograph © Madeline Djerejian)

Keep reading Dore’s writings. Dore authored or edited thirty books on art and culture, including Noguchi East and West (1992), About Rothko (1996), American Art since 1945 (1982), A Fable of Modern Art (1980), Yes, But. . .: A Critical Study of Philip Guston (1976), A Joseph Cornell Album (1974), The New York School: A Cultural Reckoning (1971), Picasso on Art: A Selection of Views (1972), The Writings of Robert Motherwell (2007), A Reading of Modern Art (1969), Rauschenberg: XXXIV Drawings for Dante’s Inferno (1964), The Unknown Shore: A View of Contemporary Art (1962), Abstract Art before Columbus (1957), and David Smith: Medals for Dishonor (1996). Her writings on art reached international audiences, as they appeared in German, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and English publications, such as Studio International, Kunstwerke, Colloquio Artes, XXe Siècle, and Art International.

Dore also organized important international exhibitions that enlarged our understanding of European postwar art. As the poet and historian Roberto Tejada has pointed out, Ashton’s voice was crucial for intellectuals and poets living in Mexico, Chile, and other countries of Central and South America. Given the enormous preoccupation today with the 1960s and 1970s, Dore’s writings during that period should be read with a fresh view.

Don’t ask her not to smoke, ever, anywhere.

Alfredo Jaar, Dore Ashton, you know, 2015, video, 9 min., 25 sec. (directed by Alfredo Jaar; cinematography by John Rohrer and Masahito Ono; sound by Joseph Mauro; artwork © Alfredo Jaar)

Michael Corris, Interview with Dore Ashton, New York, January 11, 2011, 14 min., 38 sec. (audio © Michael Corris; audio © Estate of Dore Ashton; audio produced by Clear Focus Productions, Oxford, UK). Produced as supplementary material to accompany Michael Corris, “The New York School: From Abstract Expressionism to Conceptual Art, 1940–1970”, in Paul Wood and Steven Edwards, eds., Art & Visual Culture 1850–2010: Modernity to Globalisation (London: Tate Modern and Open University, 2013)

Transcript of Michael Corris, “Interview with Dore Ashton,”New York, January 11, 2011. Produced as supplementary material to accompany Michael Corris, “The New York School: From Abstract Expressionism to Conceptual Art, 1940–1970”, in Paul Wood and Steven Edwards, eds., Art & Visual Culture 1850–2010: Modernity to Globalisation (London: Tate Modern and Open University, 2013):

Michael Corris: Now I’m going to meet Dore Ashton who as a writer on art, began her career in the late 1940s, has written for the New York Times in the ’fifties and ’sixties, and has published numerous books and articles on artists associated with Abstract Expressionism. I hope to find out how her relationship with artists likes Rothko, Motherwell, and Guston shaped her understanding of the development of the New York School, and what she thinks the main issues were that confronted these artists as they went from near obscurity in the 1940s to international celebrity by the 1960s. You were very good friends with . . . with Mark Rothko, with Robert Motherwell and Philip Guston . . .

Dore Ashton: And Franz.

Corris: And Franz Kline. OK, tell us a little bit about how you met them and how that friendship developed.

Ashton: Mainly I met them because they were all clustered in the same part of the city and so I sought them out. One of the most intelligent men I’ve ever known was Willem de Kooning—really, really intelligent.

Corris: Let’s hear some more about him.

Ashton: Well, one day I called, I was out there in East Hampton and one of the assistants said that he’s busy, he can’t receive you today, and five minutes later Bill called me and said “Come over, come over.” So I came over and we sat, and he had these two very big chairs, I guess you’ve seen them in photographs, yeah, and we talked for hours about good bad painters or bad good painters. We talked about Derain, and a few others like that and we had such a good time.

Corris: And what about Franz Kline?

Ashton: Franz was a wonderful raconteur and he was fun. At parties he would dance. He’d take two steps and then his leg would shoot out, just the way those lines shot out in the painting, really, truly.

Corris: The worlds of journalism and the worlds of art came together at that wonderful occasion known as the “opening” or, as you would say in Great Britain, the “private view.” This is where artists, collectors, journalists, poets as well, very important part of the scene, would mingle, get to know each other. After the openings they would go out to the bars and restaurants around the galleries and continue their conversations well into the night. Intellectually it gives people an opportunity to have many, many informal discussions in unguarded moments, and talk frankly to each other, lubricated by alcohol, surely, and the situation, and in fact the art becomes much more human, and the writing about it has a quality that’s very different as well. And what about Mark Rothko?

Ashton: Well, Rothko’s a different story. I went to the Betty Parsons Gallery and she had a Rothko show, and it was . . . I . . . I just was totally—what would be the word?—moved, I think is the word, by that exhibition. So then I found out he lived then on West 56th Street, right near MoMA. We had pastrami sandwiches on Sixth Avenue, and then when he’d looked me over, ’cos he was a very suspicious kind of guy, he invited me to come up and look at the work.

Corris: What did they expect from writing about their work?

Ashton: They didn’t know. Just a lot of space if possible! Some, the ones that I had really personal relationships as human beings, were interested, and then we would sometimes continue the conversation based on something that I had said.

Corris: Were they aiming not to . . . let’s say Rothko, was he aiming not to pin something down but just trying to find something that would grab the viewer and create that attentiveness and, and so on?

Ashton: You know I don’t like to say “they.”

Corris: Yeah.

Ashton: I mean I knew everybody except . . . I didn’t know Pollock well but I knew all the rest of them quite well, and each one had different drives and different satisfactions and, you know, it . . . I wouldn’t like to generalize.

Corris: At the famous round, the artists’ round table, (yes), that took place in 1950, the transcript ended with de Kooning responding to the question “Well what do we call ourselves?” And everybody sort of made some suggestions then de Kooning said “It’s always a disaster to name yourself.”

Ashton: Yes. True enough, true enough because if you think of it individually, they were each so different from the other, they had nothing technical or visual in common.

Corris: How would a student of art approach that multiplicity? You know, what . . . what do they need to know? Is it possible to just look at one individual after the next? What would you say?

Ashton: Well, a lot had to do with the war being over, so the city was flourishing, and there were studios still that were cheap to rent, plus there had never been so many art galleries. You know when I started there were fifty. When I left there were six hundred, so it was a . . . the beginning of a boom. And New York had been for quite a while, had been where . . . where the action was, as they used to say, and they were drawn to the city. So it sort of appeared . . . practical to be a group.

Corris: Do you find the . . . the . . . just the label “Abstract Expressionism” to be . . .

Ashton: Oh, ridiculous.

Corris: . . . difficult?

Ashton: Of course . . .

Corris: And . . .

Ashton: That’s why I called my own book The New York School.

Corris: Right, but even with that you spent quite a lot of time in, in that book, with sort of a disclaimer about what it meant to call something . . . call this The New York School—what exactly you were talking about. Could you talk a little bit more about that just rehearse that somewhat?

Ashton: Yes, because, because they, having been isolated for four years, five years really during the Second World War, they had to fall upon each other, and there was no longer that two-way street to Paris.

Corris: Prior to World War II it was quite common for American artists, modernist artists, to spend some time in Paris soaking up the atmosphere, often taking lessons with French artists and in general becoming familiar with Cubism and Surrealism firsthand. By the time of World War II this was no longer possible and the few American artists that had some prior knowledge of French art found themselves relatively isolated in New York. They wanted to break out of the influence of Cubism and Surrealism and yet they didn’t know particularly how to do that, so they had this very ambiguous relationship to the foundation of French culture and the School of Paris.

Ashton: I always felt that they had one foot here and one foot, they wished, in Paris. And on the one hand they . . . they had the macho verve, you know, we’re Americans and all that, and on the other hand they had . . . some of them did some very serious reading. I’d see these books around in the studio and think, aha, you know you come on with it, you’re having fist fights and being macho, drunk at four o’clock in the morning, but you’re reading these books, you know, but I never challenged anybody on that.

Corris: You mentioned in some previous conversations we’ve had about the importance of existentialism to some of these artists. Would you like to discuss that point?

Ashton: Yes I . . . I got the impression that the . . . the ones that were inclined to read and follow what was going in the world were extremely interested, and I never was able to find out, but you remember Jean-Paul Sartre gave a lecture at the New School. I was still away at school so I wasn’t there. I never was able to find out if they flocked to it but I bet they did, I bet they did—at least the ones that were thinking did.

Corris: There’s also this idea that the shift to abstraction for these artists was really fraught, in a way: that it wasn’t easy.

Ashton: No.

Corris: And it was in a . . . tremendously freighted with a lot of expectations and a lot of anxieties?

Ashton: Yes, there’s certainly . . . you’re right about that, Michael. There . . . there certainly was a high range of anxiety and whenever I went to anybody’s studio, and I don’t know what to make of that, but they were really keen to see my response when I came to the studio, which always put me on the spot ’cos I never talked in front of paintings ever and I thought “Oh god,” you know.

Corris: What about the ethical communalities?

Ashton: My impression was, and I can’t be sure, they worried.

Corris: They worried?

Ashton: It worried them, yes.

Corris: What did they worry about?

Ashton: They didn’t want to be as they used to say co-opted by capitalist America. Simple.

Corris: The Abstract Expressionists prided themselves on their outsider status with respect to American culture, dominant American culture. One of the risks that accompanied becoming more widely known as artists and celebrated was that they would be co-opted by the very establishment that they were opposing. And did they understand the ambiguity of their position?

Ashton: Some did, I think. Certainly Philip Guston was very aware of that. He was very, very intelligent and a curious man.

Corris: Do you think that awareness contributed to the shift that he made in the late ’sixties and the show that he did in 1970?

Ashton: You know, I never made up my mind about that.

Corris: Philip Guston begins his career doing highly political social realist paintings. By the late 1940s he adopts this abstract style, these very agitated fields of extremely lush color. By the mid-1960s, in private, he’s well-known for doing a number of satirical cartoons that relate to the Nixon administration, prompted by the war in Vietnam, and in 1970 he shows, for the first time, these cartoon-like paintings with figures that look like Ku Klux Klan figures, hooded figures, dismembered body parts, and all sorts of violence happening in a kind of a quasi-comic fashion. This causes a scandal in the art world, where people say that he has betrayed all of his principles as an Abstract Expressionist, has overturned abstract painting to go back to some kind of realist painting.

Ashton: My own attitude, I have to say, once I was moved by any artist, I went wherever they went and I didn’t withhold my approval, and actually I think I was maybe the only one, me and Bill de Kooning, were the only ones who defended Philip when he made the big move and had the first show of that work.

Corris: I mean you, you do point out that for you 1960 was the end, so . . .

Ashton: Well then Rauschenberg and Johns moved in and that was a whole, not that other, but other.

Corris: Were your friends talking about them, the older artists, or did they . . . ?

Ashton: The older artists were bitter.

Corris: Were they?

Ashton: Oh yeah. Mark certainly was.

Corris: And he had so much . . . he actually did have some success if you look at . . .

Ashton: Oh my, lots of success.

Corris: . . . tremendous success, he was not a poor artist.

Ashton: But you see it’s that the . . . the . . . the worldly success to almost any of those people wasn’t the success that they sought.

Corris: What were they looking for?

Ashton: They wanted to be in art history, which you can’t do in your own lifetime, and that’s one of the things I really liked about them, you know.

Corris: What Dore shows us with her account of her experiences in the art world in the 1950s and 1960s is the great revolution that has happened in the structure of the art world in New York since the end of World War II. Here we see the emergence of a fully fledged, interconnected system of institutions of the press, of the art market, of avant-garde galleries feeding into more established galleries, the divide between uptown and downtown and the infusion of art across the . . . the public consciousness. This is the great transition that happens between the end of World War II and about 1960, and this is where Dore is actually showing us the birth of the modern international art center, the cosmopolitan center of art.

Michael Corris (professor of art, Southern Methodist University) is an artist, writer, and educator. At the beginning of his career, Corris participated in the Conceptual Art collective Art & Language and was a founding editor of two significant artist-originated periodicals: The Fox (1975–76) and Red-Herring (1977–1979). Since then, Corris has exhibited and published extensively on an international level. Corris’s art works may be found in public and private collections including the Museum of Modern Art (New York), the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), Le Consortium (Dijon), Victoria and Albert Museum (London), Tate Modern and Tate Britain (London), Staatsgaleri (Stuttgart), Le Musée des Beaux-Arts (La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland), Progressive Insurance Art Collection (Cleveland, Ohio and Tampa, Florida), and Collection Philippe Méaille (Château de Montsoreau, France). The Getty Research Institute holds personal papers and artworks by Corris that are related to his work as a Conceptual artist, critic, and historian of art.

Corris’s writings on contemporary art and art theory have been published widely in journals and magazines such as Art in America, Journal of Contemporary Painting, Art Monthly, Art Journal, Artforum, Art History, and art+text. Recent monographic and coauthored publications include Conceptual Art: Theory, Myth and Practice (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), Ad Reinhardt (London: Reaktion Books, 2008), Art, Word & Image: 2,000 Years of Textual/Visual Interaction (London: Reaktion Books, 2010) with John Dixon Hunt and David Lomas, and Leaving Skull City: Selected Writings on Art (Dijon, France: Les Presses du Réel, 2016).