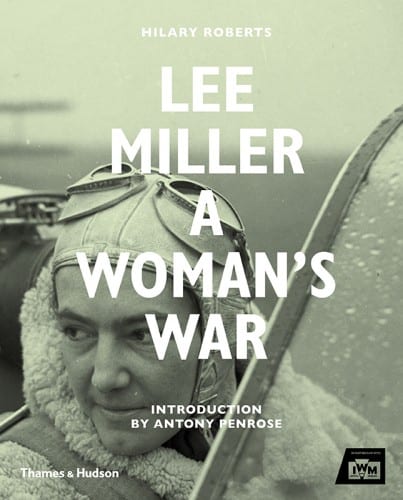

Unknown photographer, Lee Miller in steel helmet specially designed for using a camera, Normandy, France 1944, black-and-white photograph (photograph © The Penrose Collection, England 2016, all rights reserved, www.leemiller.co.uk)

Lee Miller: A Woman’s War. Exhibition organized by Hilary Roberts. Imperial War Museum, London, October 15, 2015–April 24, 2016

Hilary Roberts, ed. Lee Miller: A Woman’s War. Exh. cat., with introduction by Antony Penrose. London: Thames and Hudson, 2015. 224 pp., 156 b/w ills. $55

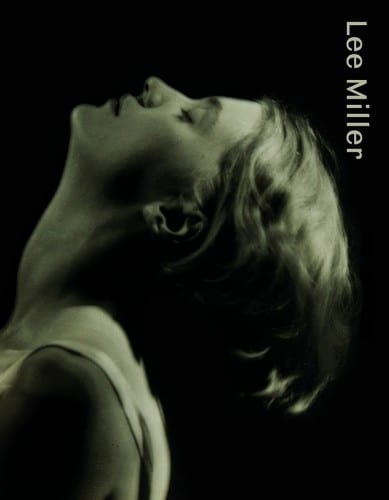

Lee Miller. Exhibition organized by Walter Moser. Albertina Museum, Vienna, May 8–August 16, 2015; as The Indestructible Lee Miller, cocurated by Bonnie Clearwater, NSU Art Museum, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, October 4, 2015–February 14, 2016; and as Lee Miller—Photographs, Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, March 19–June 12, 2016

Walter Moser and Klaus Albrecht Schröder, eds. Lee Miller. With texts in English and German by Anna Hanreich, Astrid Mahler, Elissa Mailänder, Moser, and Ute Wrocklage, and visual essays by Anna Artaker and Tatiana Lecomte. Exh. cat. Vienna: Albertina, and Ostfildern: Hatje-Cantz Verlag, 2015. 160 pp., 6 color ills., 130 b/w. $45, paper

In the past year alone, photographs by Lee Miller have been featured in two large-scale, international exhibitions: Lee Miller: A Woman’s War (London) and Lee Miller (Vienna, Berlin, and Fort Lauderdale). Both exhibitions argue that Miller’s life and work were extraordinary, an approach which is very often the emphasis of monographic shows featuring the photographer. Frequently Miller’s personal life—specifically certain experiences which could have negatively influenced her point of view—is highlighted and can overshadow the reception of her image-making in the context of the photographic medium and its history. As viewers, curators, and art historians, we cannot determine or comprehend the impact of Miller’s psyche on her work, and frankly, though it may embellish an already captivating biography, the exercise is ultimately unproductive. One can, however, both identify the characteristics of Miller’s practice that almost directly communicate Surrealist tenets or reference the history of photography, and observe Miller’s unique compositional framing of wartime scenes that were entirely lacking an art-historical language or audience. In other words, it is Miller’s photographs which should remain in focus. Rife with complexities, Miller’s almost contradictory point of view consists of a close proximity to her subjects, both living and dead, and a unique type of cool, psychological distance.

That said, a conversation with Hilary Roberts, curator of Lee Miller: A Woman’s War, revealed that the exhibition attempts to recast our vision of women’s contributions to the Second World War effort and pay tribute to Miller’s unique agility and perseverance during such turbulent world events. Viewers are encouraged to accept the idea of “war as an evolution” and discover the many ways in which women were instrumental in creating the stability necessary for constant change. Undoubtedly, the concept is an important one; the exhibition, however, looks only through Miller’s lens rather than expanding into the—albeit diminutive —spectrum of female war-correspondent photographers. For this reason, A Woman’s War appears to have been argued inversely: if Miller, then Women. A more productive strategy might read: if Women, then Miller. To attempt to understand the wartime experiences of all women, both the extraordinary and ordinary, through the lens of Miller is an ambitious objective that cannot help but fall short. If Miller is designated as the case study at hand, she is truly a unique one.

Mounted on an upper level of the recently glamorized Imperial War Museum in London, Lee Miller: A Woman’s War welcomes visitors with an oversize, three-dimensional title piece in anodized steel. Overhead lighting beams down, dramatizing each letter with intense, shadowed underscoring. Roberts explains that the title evokes Miller’s commitment to the experiences of women during the Second World War. In 1942, only one year after the introduction of female conscription in Great Britain, Miller obtained official US military accreditation as a war correspondent for Condé Nast press.1 Among her first projects was documenting the activities of both the Women’s Voluntary Service and the Women’s Royal Naval Service; Roberts notes, however, that the political atmosphere of the mid-twentieth century did not allow for much flexibility in Miller’s role. She was often assigned photo stories believed relevant to the primarily female readerships of British and American Vogue. “Fashion for Factories,” an article on how to make industrial looks more appealing for women new to the work of mass production, features Miller’s images modeling factory uniforms and masks. Despite the article’s already curious editorial pitch, Miller’s photographs show a clear connection to Surrealist tropes: the bizarre marriage of fashion and war leading to protective eyewear as the latest fashion accessory. Frequently making such references to Surrealism, Miller’s photographs are populated with mannequins, disembodied limbs, and graphic violence, in addition to her general penchant for decontextualization.

A slide show follows the title piece, displaying somewhat unrelated but diverse subjects captured by Miller: personal photos from vacations with fellow Surrealists, fashion shoots produced in the rubble of the London Blitz, and Miller in uniform at Vogue’s London studio. Painted portraits of the photographer by Pablo Picasso and Roland Penrose (Miller’s second husband) flank the large lightbox, emphasizing this early—and perhaps as the exhibition begins to imply, foremost—role assumed by Miller. Beyond the portraits, an exhibition label makes direct and detailed reference to Miller’s childhood experience with sexual assault, strongly implies her father was a predatory figure, and prepares visitors to encounter varied manipulations of Miller by sundry male figures throughout the course of her life. Such biographical details, unfortunately, set the tone of the exhibition and mark the point from which the conceptual framework—women’s experiences during wartime—begins to fray. The exhibition that follows is organized chronologically with sections focusing on “Women before the Second World War,” “Women in Wartime Britain, 1939–44,” “Women in Wartime Europe, 1944–45,” and “Women and the Aftermath of War.”

Attempting to boost morale despite the encroaching realities of war, Miller worked with Vogue UK to continue producing fashion features during wartime. Steeped in the visual tropes of Surrealism, Miller’s photographic tactics hardly change when confronted with destruction, injury, death, and eventually, the atrocities of Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps.

Lee Miller, Woman accused of collaborating with the Germans, Rennes, France, 1944, black-and-white photograph (photograph © Lee Miller Archives England 2016, all rights reserved, www.leemiller.co.uk)

In the feature essay in the exhibition catalogue, which includes an introduction by Miller’s son, Antony Penrose, Roberts posits that given these circumstances, Miller often utilizes a “feminized language” in order to appeal to Vogue’s mostly female readership (Roberts catalogue, 21). Conversely, I argue that Miller inserts highly visual language that communicates more as poetic than gendered. The majority of her wires to Audrey Withers, the social-advocacy-driven wartime editor-in-chief of Vogue UK, feature no such “feminization.” When faced with the horrors of a former Gestapo prison in Cologne and the liberations in spring 1945, Miller writes with urgency, citing Germans with “fat-covered nerves” who were deliberately overlooking the atrocities.2 Miller’s anger is palpable and her message is direct. She asks readers to recognize— rather to believe—that the torture and murder of millions took place: a message not yet fully accepted as truth in the United States. Miller, unafraid, calls Germans “schizophrenics,” “audacious”, “the enemy,” “slimy,” and “repugnant,” and warns readers to be wary of differentiating between the elite SS members and the “normal” German citizens who “ignored the activities of their lovers and spouses and sons.”3

Miller’s writing is mirrored by the extreme proximity found in her images, which often insert her directly into the scene. Miller’s step-by-step approach, as revealed by her contact sheets, differed from most other war correspondents and photo-journalists during wartime. According to friend, collaborator, and Life magazine photojournalist David E. Scherman, when faced with train cars filled with the dead at Dachau, Miller climbed inside the container in order to record the reactions of US Army soldiers. Miller crops her images to graphic squares, decontextualizes scenes, and lacks “common subjects” or perspectives which were often the focus for other war photographers. Specifically, Margaret Bourke-White, already a well-known photographer at the time and also working as a war correspondent, gained access to many of the same locations within hours of Miller. When we compare both photographers’ contact sheets with those of Scherman, Miller’s point-of-view remains uniquely close to her subjects. Although it is unclear whether or not Miller completely staged any of her wartime images by moving objects, we do know that Miller occasionally intervened by posing her subjects. In the only well-documented case of staging, Miller herself returns to the role of model with the help of Scherman. Sitting nude in Hitler’s Munich-residence bathtub, Miller’s combat boots sit before her, soiling the bathmat with the dirt and ashes of Dachau. The photographers constructed the scene together, propping Heinrich Hoffmann’s iconic photographic portrait of Hitler on one side of the bathroom and Rudolf Kaesbach’s classical nude sculpture on the other. The image was in fact published in “Hitleriana,” a story for the July 1945 issue of Vogue UK. It resurfaced during the 1990s, however, when Antony Penrose found boxes of his mother’s negatives and reintroduced her wartime work into circulation. Roberts communicated that she did not want this image, arguably Miller’s best-remembered photograph today, to overshadow the photographer’s other work. Yet its digital reprint is noticeably larger than most others presented in the exhibition.

Lee Miller: A Woman’s War also presents a selection of ephemera owned by Miller—her uniform, brass knuckles, identification cards, and even loot from Eva Braun’s Munich apartment—which form the perimeter of the show. These additions significantly complement the narrative throughout the exhibition, add to the biographical focus, and interestingly loosen the often-felt repetitiveness of photographic exhibitions by enlivening the images. This could also be the impetus behind Roberts’s decision to sporadically paint selected walls in vibrant hues, an homage to Miller and Roland Penrose’s Farley Farm house that stands in contrast to the drab colors on other walls, which are in turn meant to mimic those of female US war correspondent uniforms. Midway through the show, a darkened cinema space loops newsreels featuring Miller and her Vogue colleagues, as well as an interview with Scherman from the 1985 Channel 4 documentary The Lives of Lee Miller. The Imperial War Museum exhibition also includes some examples of images submitted by Miller to Vogue but disallowed from publication. Presented with the British Ministry of Information’s original marginalia in red and blue ink, they are the only vintage prints included in the show. The decision to produce modern digital reprints of Miller’s negatives supports an interest in creating a consistent aesthetic; however, their presentation leaves much to be desired. Although Miller was not particularly known for her printing process and often hired assistants for darkroom work, there is something to be said about seeing prints from the period of production, despite their being small and incongruous.

In sharp contrast, Lee Miller, curated by Walter Moser and as mounted at Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, features almost exclusively vintage prints in a highly diverse, yet perhaps more traditionally presented photography show. Featuring over five decades of Miller’s work through one hundred objects, the exhibition focuses on Miller’s learned “Surrealist visual idiom,” her ongoing dialogue/collaboration with Man Ray, and her development into a war correspondent (foreword to Moser and Schröder, 7). Also organized chronologically, the exhibition is installed within multiple open-bay galleries and displays some archival materials such as letters between her and Roland Penrose, as well as Miller’s photo stories in various issues of both British and American Vogue.

The catalogue features an essay by Astrid Mahler, “Formative Years: Lee Miller and Surrealism,” which draws the reader’s attention to significant arguments made on behalf of Miller’s production, autonomy, and complexity as an image-maker. Mahler introduces Whitney Chadwick’s argument that Miller was the first woman involved in the Surrealist movement “to seek an aesthetic, rather than a personal identity” (Moser and Schröder, 11),4 as well as Amy J. Lyford’s questioning of the Miller literature’s consistent return to Man Ray and his photographs of her, when attention should remain on the images taken by Miller.5 Mahler argues that “the common ‘muse-model-lover’ scheme into which the partners of famous artists are generally placed is not appropriate for Miller” and the exhibition intentionally reflects this core issue (Moser and Schröder, 11). As such, Neck (1930), an image commonly credited—concept, staging, and production—only to Man Ray, is the first image on display when one enters the exhibition. The accompanying label expounds Mahler’s argument, stating that Miller’s active role in the creation of this image suggests not just that it is collaborative in nature, but that Miller may have produced it autonomously.

In fact, Miller’s images often grappled with subject matter deemed more taboo than the work of Man Ray; she thus pushed the Surrealist envelope just as much, if not more than her male counterparts. Taken during a commissioned visit to a hospital, Severed Breast from Radical Surgery in a Place Setting (ca. 1930) portrays a disembodied female breast in the center of a stark, white dinner plate. Miller stages the image with a placemat and the proper silverware setting, perhaps presenting viewers with a graphic commentary on the treatment of female bodies in Surrealist art practice. This is undoubtedly a radical gesture, and Mahler posits further that the breast voids the sexualized male gaze, evidencing that Miller’s independence and abilities extend even further beyond the Surrealist circle.

Lee Miller with David E. Scherman, Lee Miller in Hitler´s Bathtub, Munich, Germany, 1945, black-and-white photograph (photograph © Lee Miller Archives England 2016, all rights reserved, www.leemiller.co.uk)

Following the narrative line of the show, Anna Hanreich’s essay for the Lee Miller catalogue carefully profiles Miller’s wartime photographic practice, also comparing her images to those of other female photographer war correspondents: Thérèse Bonney, Bourke-White, Georgette M. (Dickey) Chapelle, and Toni Frissell. Such comparisons still support arguments of Miller’s unmatched proximity and eye for bizarre compositions. In her essay on Miller’s images from Buchenwald and Dachau, Ute Wrocklage, like Roberts, discusses the careful military censorship process, but also reveals that some of Miller’s published images were in fact cropped by the editorial style team at Condé Nast. The most poignant example shows a group of five liberated prisoners, identified by their striped trousers, gazing at a pile of human bones. Vogue USA determined that for an American public still wary of the veracity and extent of Nazi war crimes, Miller’s image appeared too posed. As a result, they cropped the heads (and piercing eye contact) of the men, leaving only the discernable patterned uniform bottoms on view. Regardless, Wrocklage rightly notes the complexities of Miller’s process in a side-by-side comparison to photographs by Scherman, who was with Miller in both camps.

Miller and Scherman’s awareness of the National Socialist use of ideology is again striking when the Berlin exhibition draws the viewer’s attention to the series of photographs taken in Hitler’s Munich apartment, as well as in Eva Braun’s single-family home. Elissa Mailänder’s essay points to the photographers’ calculated deconstruction of the Hitler myth, noting one curious example of Miller inviting Russian refugees into Braun’s home. Miller photographs the women rummaging through Braun’s makeup, applying it in front of her full-length vanity set. Not often featured in Miller exhibitions and possibly never shown before, the image’s banality actually bears witness to the relative fragility of the cult of personality. In an act of defiance, Miller juxtaposes the domestic, private, and privileged space of Braun with the very real consequences of persecution and a small, residual triumph.

Lee Miller concludes with photographs of Vienna from one of Miller’s final wartime reports, just weeks after the Third Reich’s surrender. After fifty-three air raids and the eventual liberation by the Red Army, the occupied city lay in ruins. The exhibition displays photographs of bomb damage, hospitalized children, and black-market transactions of forbidden or rare goods. Although the official narrative portrayed Austria as a victim—in Miller’s words “liberated instead of conquered”—she is insistent in letters to Roland Penrose that the Austrians are just as responsible as Germans (Miller quoted in Moser and Schröder, 137).6 Exhibition curator Moser argues that Miller’s images are “visual admonishments” of this state myth, citing the political lucidity of her unpublished writings as significant connective tissue for interpreting her seemingly more mundane images (Moser and Schröder, 74). Viewers leave the exhibition with a sense of Miller’s development and sustained autonomy, that her competence and skill extend beyond the role of muse, student, or model. This final gallery of images from Vienna only affirms Miller’s evolution from a “desire to agitate” to a hardened, post-conflict maturity (foreword to Moser and Schröder, 7).

Similarly, Lee Miller: A Woman’s War reveals that Miller’s images are complex not because she was documenting women’s wartime contributions—this was her assignment—but rather due to her ability to bypass (some of) the boundaries of her gender role, a remarkable feat for this period. Roberts enhances this achievement with quotations by Miller posted throughout the journey-like galleries: Miller’s “visions of gender” reading as equality, freedom, and the ability to create one’s own security. Unfortunately, we are soon catapulted back into the reality that the roles Miller began to transcend still possess certain and enduring rigidities. Viewers are faced with a final, monumental lightbox image of Miller in her kitchen and then immediately confronted with the exhibition gift shop’s kitschy byproducts of museum-survival-capitalism: a compact mirror, a manicure set, jewelry.

Lauren Richman, a PhD candidate in the department of art history at Southern Methodist University, is currently conducting dissertation research in Berlin. Her research examines the photographic medium as integral to the multilayered, postwar “reconstruction” of German cultural and national identity in Cold War–divided Berlin.

- Great Britain established female conscription in 1941: unmarried women in their twenties could be sent to join the police or fire service, or to noncombatant roles in the armed forces. Other women up to the age of forty were required to register and could be directed to factories. The United States did not draft women during WWII; as a US citizen, Miller was not subject to conscription. ↩

- Lee Miller, “Germans Are Like This,” Vogue USA, June 1, 1945, 102. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (London: Thames and Hudson, 1985), 7, 38. ↩

- See Amy J. Lyford, “Lee Miller’s Photographic Impersonations 1930-1945: Conversing with Surrealism,” History of Photography 18, no. 3 (Autumn 1994): 230-41. ↩

- See also Katharina Menzel-Ahr, Lee Miller: Kriegskorrespondentin für Vogue; Fotografien aus Deutschland 1945 (Marburg: Jonas, 2005), 74. ↩