Candida Höfer, Volksgarten Köln | 1974, 1974, gelatin silver print, 7⅜ x 11 in. (18.7 x 27.8 cm) (artwork © Candida Höfer, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

It’s true, Mr. Interpreter, it’s the first time ever that a photograph of a Turk has been displayed in a German photo store. I’ve worked for more than 20 companies in Germany, in cities and in villages. I’ve neither heard, nor have I ever seen a photo of a Turk displayed in a German store. Every time I’ve gone by a photo store I’ve asked myself why aren’t we there? Why, damn it, don’t the Germans want to see us?

—Şinasi Dikman, “Hast du das Foto gesehen?”

Millions of Turkish immigrants settled in Germany after World War II to answer the call of politicians who needed to refresh the labor force after the war. Images of Turks at work or leisure in the parks, homes, markets, shops, and bars of 1970s West German cities populate Candida Höfer’s large, multiformat series entitled Türken in Deutschland (Turks in Germany, 1972–79). Höfer’s interactions with minority subjects in these images—by turns genial, jarring, and solemn—illuminate the complicated social and cultural milieu of 1970s West Germany. The black-and-white print Volksgarten Köln | 1974, for example, evokes a genuine camaraderie between the worlds on either side of the lens. Six Turkish women and a young girl relax on a blanket in a park, several of them looking directly at Höfer’s camera and laughing heartily, apparently at a joke shared with the photographer. Other images in Türken in Deutschland evoke the cultural collision that attended the influx of Turkish immigrants to postwar Germany. In an untitled color image from the slide show Höfer finalized in 1979, the artist concretizes the uncomfortable clash between Turkish and German cultures; an attractive father and daughter wearing neat white coats stand behind the glass counter of a Turkish meat shop, smiling in a familial way for the camera. Blood-red sausages and an assortment of discordant advertisements in Turkish and German frame the pair, competing with each other for visual attention. Still other images evoke a sense of quietude with Höfer cast as an appreciative observer of the artifacts of the Turkish presence in Germany. In another image from the 1979 slide show, Höfer presents a tightly framed view of the front window of a Turkish export store. Superimposed over the store goods are the reflections of cars and buildings; rows of exotic tea sets, china, knickknacks, electronics, flags, and headscarves combine visually with the German streetscape. At the center of this layered vision is the subtle reflection of Höfer’s own body, exposing her as the observer and framer of the scene. In these and many other images in Türken in Deutschland, Höfer explores the presence of Turkish migrants in 1970s Germany and how that presence was alternately erased and revealed in relationships with the dominant German culture.

Türken in Deutschland circulated among contemporary audiences in multiple, unique ways. Starting in the mid-1970s, Höfer exhibited black-and-white prints and color slide shows in galleries in her hometown of Cologne and the flourishing art scene of nearby Düsseldorf. In 1977 and 1980, Höfer also published little-known works called Diaserien, sheets of slides printed alongside informational texts that Höfer commissioned sociologists to write about the Turks’ history, culture, and current situation in Germany.1 The images in these Diaserien are similar, sometimes identical, to those Höfer hung or projected in art venues, but they targeted audiences in schools and community centers and aimed to work with text to educate a population that suffered from a conspicuous shortage of information about the Turks.2

Höfer’s images of Turkish migrants, with their straightforward depictions of politicized subjects, were anomalous at a time when the expressive, inward-looking, and technically experimental style of “Subjective Photography” dominated photographic practice in West Germany.3 (Bonn: Brüder Auer, 1952); and L. Fritz Gruber, “Zum zehnten Male,” paper presented at Photokina 1968: Bilder und Texte, Internationale Photo- und Kino-Ausstellung, Cologne, September 28–October 6, 1968.] Höfer’s Türken in Deutschland defies neat categorization: the images do not gawk at squalid living conditions or exotic cultural practices, or even feature dramatic expressions of emotion that might make particular images appear to symbolize larger issues. Instead, they express the frankness and intimacy of family snapshots, as well as an interest in new aesthetic mediums of the postwar avant-garde.

Candida Höfer, Untitled from Türken in Deutschland 1979, 1979, color slide projection, 80 slides, approx. 7 minutes, dimensions variable (artwork © Candida Höfer, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

For all its historical significance and aesthetic novelty, Türken in Deutschland is largely overlooked today, particularly outside Germany. The Guggenheim’s online biography of Höfer fails to mention any of her projects from the 1960s and 1970s, instead beginning with her Räume (Spaces) series of the 1980s.4 Her most recent retrospective, Candida Höfer: Düsseldorf, premiered in Germany with several 1970s images of West German Turks, yet when the exhibition traveled to New York, the early photographs were omitted in favor of presenting a harmonious vision of Höfer’s practice as purely devoted to unpopulated, visually sumptuous architectural interiors.5 Few curators and art scholars today even know of Höfer’s Diaserien, and the artist herself claims they are no longer relevant to her oeuvre.6

Of the scholars interested in Höfer’s work today, the few who discuss Türken in Deutschland often contextualize it within the so-called Düsseldorf Photography School. Höfer, no doubt, played a vital role in this circle by the late 1980s. Yet to associate Türken in Deutschland with the Düsseldorf Photography School is to misrepresent the project as a student’s emulation of her mentors’ methods and aesthetics when Höfer, in fact, began Türken in Deutschland almost four years prior to her participation in Bernd and Hilla Becher’s groundbreaking photography course at the Kunstakademie.7 Other scholars discount Türken in Deutschland altogether as an early artistic slip into the problematics of representing social minorities from a position of greater power.8 This criticism is addressed later in this essay, yet suffice it to say that such a critique fails to recognize the immediate cultural, political, and aesthetic contexts of West Germany in the decade during which Höfer produced the work. The most significant contextual factor, I will argue, is the consistent institutionalized erasure of postwar foreigners from mainstream media and culture.

This essay seeks to clarify how Türken in Deutschland in all its formats served a social and political function in the 1970s West German public sphere. Specifically, it worked to combat representational norms in contemporary visual culture through its aesthetics, material formats, and modes of circulation. To advance this claim, I first historicize Türken in Deutschland by situating it in a fuller sociopolitical, intellectual, and cultural context. Then, I consider the project in terms of its multiple material formats: black-and-white prints, slide shows, and slide publications. Finally, I theorize Türken in Deutschland by interpreting it as an instance of Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge’s “counter-publicity.” In their coauthored 1972 book Öffentlichkeit und Erfahrung: Zur Organisationsanalyse von bürgerlicher und proletarischer Öffentlichkeit (Public Sphere and Experience: Toward an Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere) Negt and Kluge articulated that, in order for minorities to attain access to the democratic public sphere, they need “publicity,” or representation in visual and other creative media that is rooted in their distinct life experiences.9 Höfer’s photographs of Turks inhabiting everyday leisure, work, and domestic spaces in West Germany answer this call. I argue that the Diaserien and gallery projections, in particular, made Turkish migrants visible at a time when their presence in the public sphere was limited and controlled for official ends. Ultimately, Türken in Deutschland functioned in the 1970s to enhance visibility and produce public discourse for and of a disenfranchised minority group; that is to say, it was “counter-publicity.”

The essay will also explore how Höfer’s slide shows extended local art experiments with projection technologies to similarly discursive and public ends. By analyzing Türken in Deutschland in relation to these regionally centered art practices and discourses, we see that Höfer’s 1970s project was actively working with pressing social debates and artistic questions beyond those typically associated with the Düsseldorf Photography School. In fact, Höfer’s photographs of Turkish migrants give us crucial insight into the artist’s career-long investigation of public space and the public sphere, and they have continued resonance in our era of mass population displacement.10

Historicizing Türken in Deutschland

The influx of Turkish migrants to Germany began when the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) instituted its foreign labor recruitment program in 1955 in order to supplement the labor force after the country lost almost three million men in World War II. The newly capitalist nation drew blue-collar workers known as Gastarbeiter, or “guest workers,” from Italy (starting in 1955), Spain (1960), Turkey (1961), Morocco (1963), Portugal (1964), Tunisia (1965), and Yugoslavia (1968).11 From the outset, policymakers presented the guest worker program to the public as strictly a temporary solution and the only viable one for the nation’s demanding agenda for economic growth. Through the 1960s, few envisioned (or admitted) that recruiting foreign laborers would bring long-term social or cultural changes to a country already deep in an identity crisis after being divided into communist and capitalist zones.12

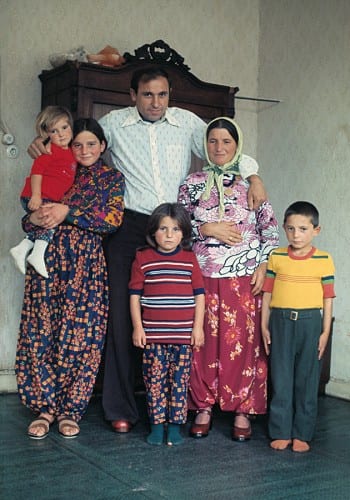

Candida Höfer, Untitled from Türken in Deutschland 1979, 1979, color slide projection, 80 slides, approx. 7 min., dimensions variable (artwork © Candida Höfer, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

Höfer began photographing the booming Turkish guest worker community around 1972, precisely when policy changes had profound effects on the population demographic. Before 1970, German authorities, employers, and foreign laborers alike understood labor recruitment by its “nonpermanency”—that is to say that Germans and migrants believed laborers would return to their economically depressed nations of origin after quickly earning as much money as possible in the Federal Republic.13 However, when the international oil crisis brought the German “economic miracle” to an official halt in 1973 (and consequently, ended its labor recruitment program), workers did not always return to their homelands as planned. Above all others, Turkish guest workers stayed and began securing resident visas for family members to join them.14 By the mid-1970s, Turks outnumbered all other foreign residents in West Germany, and the initially multinational character of the labor recruitment program was largely forgotten.15 The term “guest worker” became predominantly associated with the Turks and their particularly contested migration. While guest workers of all nationalities experienced feelings of dislocation, alienation, and injustice, citizens largely perceived the Muslim Turks as the greatest threat to German culture and identity.16 As evidenced by pervasive problems with social and legal discrimination, Germans neither welcomed the Turks’ presence, nor accepted the changes the non-Western “Others” brought with them.17

Despite the dramatic increase in the Federal Republic’s foreign population after 1955, popular films, books, newspapers, and advertisements of the era rarely included representations of foreigners except in ways that served policy needs or succumbed to ethnic stereotyping. The historian Rita Chin points out that in the first several decades of labor recruitment, guest workers had limited visibility in the West German public sphere and restricted access to venues for publishing firsthand literary accounts of their experiences.18 Because foreign laborers of the time predominantly viewed their residence in Germany as temporary, few of them learned German. While many documented their experiences in their native languages in private journals, letters home, or foreign publications, few writings by migrants made it to the mainstream German public in the early postwar decades. Thus, when discussions or representations of guest workers did appear, Chin claims, they were offered only from the perspective of someone of the majority class.19 This is to say that, in the 1970s when Höfer produced Türken in Deutschland, Turkish immigrants were being spoken for, if they appeared in print or the visual environment at all, and these representations were not always consistent with their lived experiences in Germany.

This form of silencing and erasure persisted until the 1980s, when Turkish authors began to publish poetry, short stories, novels, and biographies in German for majority audiences to read.20 The excerpt from Şinasi Dikman’s satirical short story “Hast du das Foto gesehen?” (“Did You See the Photo?”) that begins this essay is one such example. Dikman’s tale powerfully describes the Turks’ recognition of their exclusion from the visual environment of postwar Germany and their attending desire for (photographic) representation. Moreover, the Turkish writer makes it plain that, even by 1983 when the story was published, Germans firmly resisted such change.

Deutsche Presse-Agentur, Photograph of Armando Rodrigues, the millionth guest worker, September 10, 1964, gelatin silver print (photograph © DPA/Landov, provided by DPA)

In the early postwar decades, two mainstream news events strongly shaped the German perception of guest workers and were intended to sway the public concerning immigration policy: the publication of both the first labor recruitment treaty with Italy in 1955 and the 1964 Deutsche Presse-Agentur photograph of Armando Rodrigues’s arrival as the one-millionth postwar migrant worker. The first was a textual representation of the otherwise anonymous foreign worker on the brink of appearing in West Germany; the treaty defined postwar guest workers unequivocally as temporary presences in the nation and necessary for the country’s economic success.21 The second was the first widely circulated image of a guest worker in the public sphere. The famous photograph of the public relations event depicts the able-bodied Rodrigues in a train station, holding flowers, and sitting on a motorcycle he had been given by German officials who surround him and enthusiastically applaud for the camera. The photograph and its description in German newspapers served as the authoritative “ideological construction of the guest worker in rhetoric and imagery” through the 1960s.22 Laced with patriarchal and xenophobic symbols, the photograph presented the public with an impression of the Federal Republic as the rich and generous benefactors of poor foreigners who would dutifully serve the nation’s economic needs—and then leave.

Around 1972 when Höfer began photographing Turkish families and groups in public and private spaces, few additional representations of guest workers existed in mainstream media, particularly firsthand or collaborative ones. Consider the difference between the Deutsche Presse-Agentur’s representation of Rodrigues and Höfer’s presentation of guest workers. In the first two images of Höfer’s 1979 slide show, a Turkish man stands surrounded, not by German officials, but by his wife and children whom he embraces with a proud smile. While the context of his home is limited to a small corner, it is decorated smartly with an armoire and small table. Gone is the awkwardly authoritative context of the Rodrigues photograph and its careful staging in a train station, which visually reinforces the guest worker’s transient presence in Germany. In Höfer’s photographs, the Turks are not ghosts in a German world but a fixed and growing population in the process of creating meaningful spaces of their own.

Höfer was not alone in defying 1970s representational trends by focusing on the experiences of foreign laborers in Germany. By the 1990s, the widespread omission of guest workers from German literature became the subject of substantive scholarly research, and, as early as 1968, a tight circle of avant-garde writers and filmmakers began to present a fuller picture of guest workers and the living conditions they experienced in the Federal Republic. Although scholars have not yet analyzed Türken in Deutschland in relation to either of these fields of study, such an analysis enhances our understanding of Höfer’s art and the postwar German public sphere in which she worked. As this essay shows, Höfer was not working within an artistic vacuum as a devotee of a single school of photography. The concepts, means of distribution, and themes at the core of Türken in Deutschland relate powerfully to the work of academics and of avant-garde writers and filmmakers of the era who analogously identified guest workers as marginalized and challenged the public with alternative visions of migrant experience.

According to Gail Wise, even by the early 1980s in the Federal Republic, “a dearth of popular images indeed existed, not only of Turks, but also of the millions of other foreigners who were living in West Germany as a result of the foreign worker migrations of the Fifties, Sixties, and Early Seventies.”23 By the 1990s, a group of German and American scholars had formed a new academic field to study creative culture by or about guest workers, termed Gastarbeiterliteratur. These intellectuals identified the pervasive practice of excluding postwar foreigners from visual and literary works as a kind of “silencing”—a term that describes both the language barrier most guest workers faced and their systematic exclusion from the creative, public sphere. Arlene Akiko Teraoka explains this phenomenon aptly in 1987. She offers examples of the way Turkish migrants are depicted as silent or prelinguistic characters in German films and plays from the late 1970s and the 1980s and argues that, during the previous twenty-five years, “from the German point of view, Turks have been an indecipherable, silent presence in West German society.”24 She adds that guest workers, particularly the Turks, were and still are silenced by infrequent or stereotypical depictions in mainstream German scholarship and media.25 Only by the 1980s, she claims, when Turkish foreign workers began learning German and publishing in the majority language, did “the opaque Other” break its silence and begin to speak back to the West.26

In German novels and films of the 1960s and 1970s, Heinrich Böll, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Helma Sanders-Brahms, and Alexander Kluge produced original, though sometimes brief, depictions of foreign laborers and the difficult challenges they faced in their nominal country. Böll received the 1971 Nobel Peace Prize for Literature after writing a pseudo-documentary novel Gruppenbild mit Dame (Group Portrait with Lady), which revolves around a woman in postwar Germany who falls in love with a Soviet prisoner of war and develops a close friendship with a Turkish guest worker.27 In her dissertation, “Ali in Wunderland,” Gail Wise criticizes Sanders-Brahms and Fassbinder for creating foreign characters that outwardly follow stereotypes about guest workers as silent, passive, or lacking in agency; yet, she claims, there are also elements in both filmmakers’ works that potentially render those depictions farcical or otherwise highlight them as stereotypes to be reconsidered The woman’s defiance of West German social norms mandating the separation between citizens and all foreigners (particularly between women and foreigners) is an early narrative representation of dominant stereotypes and stigmas foreign residents faced at that time.

Candida Höfer, Untitled from Türken in Deutschland 1979, 1979, color slide projection, 80 slides, approx. 7 min., dimensions variable (artwork © Candida Höfer, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

Fassbinder, the enfant terrible of New German Cinema who established an early reputation for brazenly criticizing bourgeois values, sexual mores, prejudice, and violence, made two films that draw attention to the nation’s deeply ingrained xenophobia during the era in question. His experimental film Katzelmacher (1968) is one of the first works in the German cultural sphere to address hate crimes against guest workers. The plot involves a group of bored, financially and sexually troubled young adults who direct their frustrations toward a migrant worker who moves into their apartment building. After the guest worker (played by Fassbinder) starts dating one of the women in the group, the other women lash out at her verbally and the young men give him a brutal beating. Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974) again takes up the theme of guest workers, this time in a melodrama about a lonely, aging German woman who develops a passionate relationship with a young, attractive Turkish worker. Because of their relationship, the couple experiences rage from their community, discrimination, and sequestration. Both films illustrate how decisively the lines were drawn between Germans and foreigners at the time.28

Sanders-Brahms’s 1975–76 feminist film Shirins Hochzeit (Shirin’s Wedding) also addresses the collision of sexual dynamics and ethnicity in West German culture. In it, a young woman from rural Turkey, Shirin, escapes an arranged marriage to follow a man she loves to Germany. There she finds locals who help her get established in the new country as she continues her search for him, but when she loses her job in the 1973 economic crisis, she is raped and forced into prostitution only to find her lover right before her tragic end. With Shirin’s Wedding, Sanders-Brahms tells a story about the experiences of guest workers from a much-needed female perspective, describing the unique communities that foreign women could find in West Germany, as well as the potential, additional layers of sexual discrimination and violence.29

Kluge rarely addresses foreign laborers directly in his films or in his cowritten book Public Sphere and Experience, except perhaps for a brief scene he directed for the 1978 omnibus film Germany in Autumn, in which the German police harass a Turkish man. Yet his claims that strong democracy rests on equitable access to publicity have clear implications for the situation of guest workers. Negt and Kluge firmly oppose the classist biases of earlier theories of the public sphere in their book. By expanding their theory beyond the bourgeoisie, they deduce that the production public sphere, which includes mass media and the media cartel, “oscillates between exclusion and intensified incorporation: actual situations that cannot be legitimated become the victims of deliberately manufactured nonpublicity.”30 Erasing Turks from mainstream visual and literary production is an expression of this concept.

Höfer would have been exposed to New German Cinema and surely to Kluge’s concept of counter-publicity as articulated in Public Sphere and Experience.31 Her advanced art education began at the Kunstakademie from 1973 to 1976 in the film class of the Danish avant-garde filmmaker Ole John, who wrote and directed activist, alternative films, frequently collaborating with Joseph Beuys.32 Whatever Höfer’s direct level of exposure, when she began Türken in Deutschland, she joined these leftist writers and filmmakers in combating minority “nonpublicity” with novel photographs of the everyday spaces and experiences of Turkish guest workers.

Candida Höfer, Rudolfplatz Köln | 1975, 1975, gelatin silver print, 7⅜ x 11 in. (18.7 x 27.8 cm) (artwork © Candida Höfer, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

Like Shirin’s Wedding, Group Portrait with Lady, and Fassbinder’s films, Türken in Deutschland also addresses the sexual dynamics and proscriptions surrounding guest workers and Germans. A surprising number of Höfer’s images, across all formats of the series, are of all-male groups. Most of the pictures taken in stores, bars, cafes, and public streets are of all-male groups, including an extended sequence of images two-thirds of the way through the 1979 slide show and Rudolfplatz Köln | 1975 from the print series. In these images, Höfer’s “authority” as the creator and organizer of the gaze is undercut by strongly returned male gazes, which typically evoke some combination of amusement, suspicion, and desire. Given the projected format of the Türken in Deutschland slide show, the repetition of large-scale, color photographs of men staring back at the photographer with aggressive and/or flirtatious gazes has a particularly jarring effect.33 The slide depicting four seated men staring intently at Höfer, one with an inviting half-smile and a cigarette hanging languidly from the corner of his mouth, is especially potent because of the image’s unusually tight framing, which places Höfer (and the viewer) very close to their bodies. In tune with the thematic assertions in Böll’s book and New German Cinema, Türken in Deutschland makes visible the social conflicts policy makers and mainstream media producers aimed to hide. Yet Höfer’s photography also asserts that she, a German and female artist, is embedded within the interpersonal, gendered, and sociopolitical dynamics of West Germany’s newfound multiculturalism.

By the 1970s and 1980s, documentary-style projects like Türken in Deutschland that depict social, racial, or economic minorities would be characterized by some intellectuals as voyeuristic, even violent. For example, the photography critic Susan Sontag writes in 1973 that “to photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed,” and in 1986, Edward Said claims that “the act of representing others almost always involves violence to the subject of representation.”34 Such critiques of photography and other forms of visual representation are no doubt necessary correctives to the use of pictures to reinforce racist, classist, or sexist ideologies. Yet a close examination of Türken in Deutschland in context suggests a very different motive and meaning for these photographs. In Höfer’s West Germany of the 1960s and 1970s, the politically advantageous position was to erase, ignore, and silence foreigners. Historicizing Türken in Deutschland and analyzing its strategic use of imagery and innovative formats enables us to see how the work actively sought to challenge the public with alternative perspectives of a contested population.

This is a view that has not been taken seriously in art scholarship thus far. Even Höfer’s longtime friend Benjamin Buchloh, in his first-ever essay on her art from 2013, critiques Türken in Deutschland as not fully representing the Turks as a social category. He sees Höfer’s early project as a failed attempt to operate in the heritage of August Sander, and he claims that her lack of comprehensiveness renders the work voyeuristic.35 Buchloh’s essay approaches the problem of photographing others from a Marxist perspective in a way that is highly relevant historically, yet he fails to take into account the Federal Republic’s dominant practice of rendering Turks invisible in cultural production at the time Höfer was working. The 1970s practice of negating the Turks in West German literary and visual culture was a historically and geographically specific expression of majority power and oppression of social Others that, I claim, Türken in Deutschland worked against in radical, not voyeuristic, ways.

Höfer’s strategies as a photographer must be distinguished from those of most European and American street photographers of earlier postwar decades. Höfer did not approach her documentary-style project by clandestinely shooting Turkish groups in public spaces. Instead, she talked with her subjects, asked them for permission to take their pictures, and eventually entered their homes as a guest.36 In an interview from 2007, Höfer describes the onset of the project in this way:

It had all started in parks in Cologne. I felt somewhat touched by the ease with which Turkish families adopted this environment for their picnics and their family life. I became interested; I approached them; they did not mind being photographed. In time, they invited me to their homes, to their restaurants and shops, to the streets they were living in. . . . Being in their homes was not even mainly about photographing. They had questions to ask, stories to tell; they had forms that needed to be filled out. I felt their strong wish to be accepted, to become integrated, to belong. And it was me who felt accepted and integrated. The friendliness with which they treated me, although I was not a member of their group, was really overwhelming.37

Höfer’s photographic method is characterized by compassion and respect for the Turkish community. Her sustained engagement with it over the course of the decade moves beyond hunting images of exotic Others and taking “snapshots” in the mold of Said and Sontag’s distanced, violent photo-documentarian.

With Türken in Deutschland, Höfer is self-critical about her relationship to her marginalized subjects, and she desires to do more than merely offer images of Turks for facile visual consumption. On a pictorial level, her images possess a sense of openness, reciprocity, and critical analysis of visual and social power structures. Höfer’s subjects typically exhibit agency and a playful banter with the camera that suggests a form of photographic “giving” rather than “taking.” This is clear throughout the slide show, which offers a steady stream of portraits of Turks who look back with a sense of self-presentation and congeniality—signs they are willing agents in the act of photographic representation and have a rapport with their photographer. Höfer brings the kind of reciprocity I am describing to the fore when she includes her own faint reflection in pictures of storefront windows, placing the image of her body within the Turkish spaces and places she depicts. This strategy complicates typical power structures of the gaze, and it occurs in multiple slides of the 1979 projection. Consider, for example, the slide illustrating Turkish men in suits who all smile and directly engage with Höfer from behind the window of an imported goods store. In the center of the image, we see Höfer’s body reflected clearly in the storefront glass, face obscured by her camera. The image is layered with objects, bodies, and architectural forms from both sides of the glass that flatten the image and place the people—a German photographer and several Turkish subjects—on one equal plane.

Candida Höfer, Untitled from Türken in Deutschland 1979, 1979, color slide projection, 80 slides, approx. 7 min., dimensions variable (artwork © Candida Höfer, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

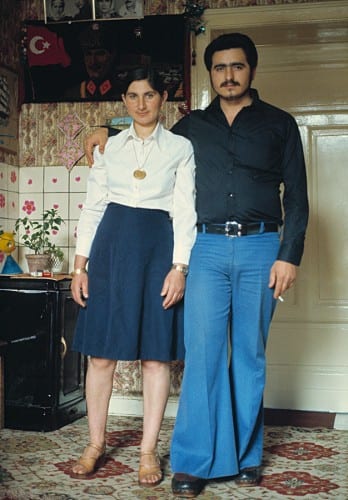

This reciprocal dynamic of looking and looking back is one of the ways in which Höfer’s project affords representational agency to her minority subjects, yet the photographs also generally have a level of specificity that does not allow for the simple visual appropriation of the people on display. Viewers see some pictures of people in traditional Turkish clothing picnicking or gathering in ways that might be understood as “typically Turkish” and yet just as many others in contemporary, westernized fashions as they work, shop, do homework, or otherwise perform the rituals of everyday life in a postwar capitalist nation. Even within individual slides and prints, we see multiple possibilities about how Turks negotiate their identities and experiences in Germany, as, for example, in the wide variety of clothing choices and hairstyles of the women in Volksgarten Köln | 1974 or in the untitled slide depicting a young Turkish couple standing in a kitchen wearing stylish clothing and jewelry. Here, the room’s décor shows a similar attempt at mixing Turkish and Western cultures with its combination of simple tiles and utensils with Turkish carpets and a Turkish flag. Across the series, Höfer does not offer a unified vision about Turkish difference or acculturation. She visualizes Turks as embedded in the West German social sphere without resorting to stereotypes or pathos.

The Multiple Formats of Türken in Deutschland

In the years before she created Türken in Deutschland, Höfer focused on producing black-and-white 35mm and medium-format photographs but was exposed to an array of other modes of expression. She interned at the celebrated Fotoatelier Schmülz-Huth in Cologne (1963–64), studied art at the Kölner Werkschulen (1964–68), and worked as a freelance photographer and artist in and around Cologne until 1970. She was close with a circle of local leftist thinkers and avant-garde artists, including the anthropologist Michael Oppitz; Fritz Heubach, the editor of the contemporary art magazine Interfunktionen; Buchloh, a gallerist and emerging Marxist art critic; the young sculptor Isa Genzken; and the radical, mixed-media artist Sigmar Polke. Höfer’s interest in the Turkish community began after a two-year hiatus in Hamburg from 1970 to 1972.38 Upon returning home to Cologne, Höfer observed with fresh eyes how quickly the Turkish population had grown. While visiting Oppitz and Buchloh at their apartment, she became interested in how Turks were using the large park across the street frequently and in more social and leisurely ways than Germans.39 As more Turkish families entered the park, however, fewer German families used the space, and the demographic of the neighborhood quickly shifted in a reactionary way that intrigued the young photographer.40 Höfer began approaching these Turkish families and groups for permission to photograph them in black-and-white 35mm film.

In the fall of 1973, Höfer moved from Cologne to Düsseldorf, where she took up a powerful new medium: color slide projection. She finished a year of general art studies at the Kunstakademie and two years in the film course with Ole John, who encouraged her to continue documenting Turkish guest workers. It was with John’s support that Höfer decided to project color slides as a marriage between film and photography.41 Continuing in the unassuming, snapshot style of her black-and-white prints, she began creating multiple slide show projections from color slides that she often shot in tandem with the black-and-white photographs. She exhibited the slide shows and prints in the 1970s and early 1980s in art galleries and museums across the Rhine region.42 The black-and-white prints have individual titles, and early slide shows have distinct titles, but by 1979 Höfer had finalized the content and sequence of the eighty-image slide show that she still exhibits today. She titled it simply Türken in Deutschland, a title she now uses to refer to the larger series. In 1977 and 1980, Höfer would try out another medium: she published sets of her slides in the form of Diaserien, or slide series, in which sheets of slides were published with sociologists’ writings about the Turks’ culture and history. Höfer’s choices in media were not only aesthetic but also political. Both the slide projection and the Diaserien had an avant-garde, experimental quality, and even more to the point, they were vividly public in nature.

The slide show format that Höfer chose is born of a desire to address viewers in a spectacular fashion and literally to change the visual environment of West Germany by projecting its marginalized, silenced people boldly into its public spaces. The works exist within a longer history of Cologne-Düsseldorf region artists using projection as an avant-garde means of intervening aesthetically in architectural sites and challenging the dominance of painting and sculpture. Artists such as Otto Piene, Imi Knoebel, Heinz Mack, and Günther Uecker were some of the first in West Germany to use projection technologies; they explored the medium for its potential to create social discourse and new aesthetic experience. Their work laid a foundation for young Höfer to adopt the unusual medium in order to create anti-institutional spaces that combine spectacle, spatial engagement, and sociopolitical critique.43

Candida Höfer, Untitled from Türken in Deutschland 1979, 1979, color slide projection, 80 slides, approx. 7 min., dimensions variable (artwork © Candida Höfer, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

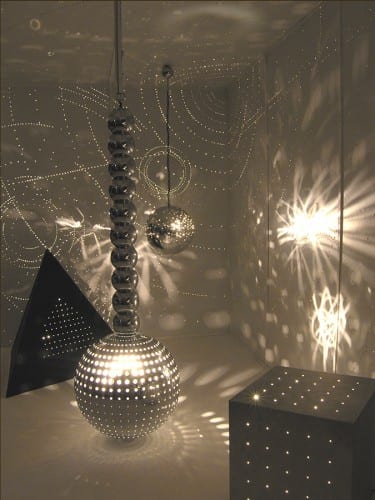

The forefather of German projection is Piene, a student at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie with Joseph Beuys in the 1950s and one of the founders of the experimental, new-media art collective known as Zero Group.44 By the late 1950s, Piene began creating artworks from light projected through punctured surfaces and machines with rotating globes and discs, often set to music. The resulting array of moving lines, dots, and other shaped light forms scattered across the walls and ceilings of exhibition spaces, producing what Piene continues to call Lichtballeten (Light Ballets). His influence grew through the 1960s, both inside and beyond West Germany.45

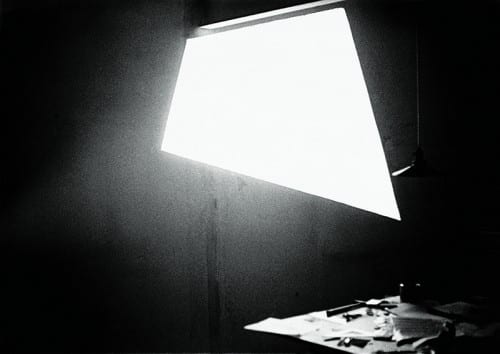

The Dessau-born Knoebel would soon emulate Piene, by taking up the projector as an art tool. Knoebel studied under Beuys at the Kunstakademie (from 1964 to 1971) and began making minimalist projections of pure light in 1969.46 Rather than adopting Piene’s kinetic projection machines, Knoebel preferred the standard carousel slide projector (the kind that Höfer would later adopt) filled with blank photographic slides often marked with ink to create perfectly shaped casts of geometric light, as with Innenprojektion (1969). Between 1970 and 1972, Knoebel took the projector outdoors and drove through Darmstadt projecting a large “X” onto the buildings and walls of the city from inside his car. He recorded the action with a forty-minute video called Projektion X, in which viewers watch a continuous stream of projected light enliven the nighttime cityscape.

For twenty-first century viewers, a carousel slide projector may seem like a technological relic, but in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it was cutting-edge visual equipment. Typically marketed to the public as a tool for teachers and salespeople, it was also a means for families to view their photographs at home in large format. As artists worldwide moved away from traditional art mediums, some were drawn to projectors for the kinds of new creative and spatial possibilities evident in Piene and Knoebel’s work.47 Along with the medium’s alluring scale and color, slide projections were attractive to artists because of their familiarity to viewers. Darsie Alexander points out that by the 1960s “slide projection represented a common ‘language’ that the general public could understand, but it also engaged the concerns of artists seeking to explore the principles of art as a fugitive process, a projection of ideas and images.”48 The medium’s accessibility and ability to display a combination of “ideas and images” in a novel, public fashion are fundamental to the way Höfer’s slide shows and Diaserien functioned in the 1970s.

Candida Höfer, Untitled from Türken in Deutschland 1979, 1979, color slide projection, 80 slides, approx. 7 min., dimensions variable (artwork © Candida Höfer, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

Although slide show projections are generated from photographic images, they radically depart from traditional color or black-and-white prints in their visual impact. For viewers accustomed to looking at static paintings and sculptures, projected images possessed a new temporality, scale, and psychological power. Doreen Bolger points out that from diminutive photographic slides, artists from the 1960s on “have produced magnificent images, projected with an unsurpassed clarity and intense color on a scale that exceeds even the most ambitious paintings of the time.”49 Artists of the postwar era experimented widely with the timing and sequencing of images in their slide shows, specifically because such factors could alter the effect of their images on viewers and test the way people were accustomed to looking at art. In this way, Alexander claims, “The medium thus played upon and accentuated one of the most significant aspects of performance art: it was a form of human discourse, promoting a dynamic interaction between people, politics, and art.”50

Following Piene’s Lichtballeten, he and other Düsseldorf artists of the late 1960s began thinking of projection in increasingly discursive, environmental, and embodied terms. From the onset of their collaboration as Zero Group, Piene, Mack, and Uecker held one-night exhibitions and actions or demonstrations as a means of exhibiting their work; in the 1960s, Uecker carried the group’s self-proclaimed interests in making “works of light and movement, space and time, dynamics and vibration” to an experimental art space and disco in Düsseldorf called Creamcheese.51 When it opened in July 1967, at 12 Neubrückstrasse in the old town, near the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie, Creamcheese was conceived as a space to combine pop and electronic music with slide projections, light shows, films, and other visual objects or installations.52 The filmmaker Lutz Mommartz and the media artist Ferdinand Kriwet worked together at Creamcheese to facilitate local artists’ use of the building for Happenings, events centering on the display of large-scale two-dimensional art works and of multiple simultaneous projections of light, pictures, and text. In the tradition of Piene and Knoebel’s spatialized projections, the club’s visitors would dance in and around the beams of light and imagery, becoming part of the environment.

Höfer’s first exhibition of her slide projections took place in 1975 at Konrad Fischer’s small Neubrückstraße gallery near Creamcheese. Fischer built the exhibition space in 1967 (the same year Creamcheese opened) by enclosing the open end of a small, covered alleyway with big glass doors, leaving the interior of the gallery visible to street traffic. By the time of Höfer’s exhibition, Fischer was using the space for work by emerging local artists. For her exhibition, Höfer installed two projectors with color slide shows, one of images of Turks living in West Germany and another of Turks in their homeland that she and Gerard Osborne had shot that summer.53 Thus from the street the Creamcheese crowd, which consisted of many Kunstakademie students and teachers as well as local artists, filmmakers, and musicians, could see a double projection of large-scale, color images of the booming Turkish community late into the night.54 Extending the tradition of artists before her, Höfer transformed her politicized images into spectacular and environmental works of art.

Otto Piene, Light Ballet (Lichtballett), 1961, metal armature, lamps, motor, and rubber, 70 x 61 x 31½ in. (178 x 155 x 80 cm). Foundation Museion, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Bolzano, Italy (artwork © Otto Piene/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

Even as her double projection in a glass-box gallery rhymed with the spatial projections in Creamcheese, Höfer’s work was much more explicit than Piene, Knoebel, and Uecker’s in its sociopolitical ambitions. Höfer and Osborne chose a title that emphasized the need for action—“WAS not tut . . . ist eine weitgehende Integration der Gastarbeiter” (WHAT Is Needed . . . is a far-reaching integration of guest workers)—and included examples of structural hostility against the Turks with a display of newspapers referring to guest-worker stereotypes.55 For the art critic Gislind Nabakowski, and I suspect many of the locals passing by Fischer’s gallery, Höfer’s projections were understood as a pointed attack on policies concerning minorities.56 They were a bold, spectacular call for discourse and action to help integrate Turkish immigrants. Her imagery offered a disenfranchised minority the kind of “counter-publicity” that Negt and Kluge (and the New Left) felt was necessary to bring a working-class population to equality in the young Federal Republic.

Just as Höfer’s slide projections used a new art medium to create immersive imagery that, in itself, generated a counter-public sphere in 1970s Germany, so too her Diaserien operated with similar discursiveness. The published slides and text, though, were designed and distributed to reach non-art audiences. At the time of publication, few sociological or cultural texts were available on Turkish customs, history, and beliefs to help German readers develop a greater understanding of their new neighbors—and to help Turkish immigrants understand themselves as inhabitants of Germany. The sociologists whom Höfer asked to author Alltag in der Türkei wrote that the shared ambition of the trio was for the projected slides and text to be used together to help, for example, Turkish schoolchildren bridge the gap between their home lives and the public schools where they were broadly identified as struggling.57 Seeing images of Turkish families in their homeland and reading information about their history and culture would, Höfer and the sociologists hoped, encourage minority children to talk in front of their German peers about their new lives and struggles in the Federal Republic. In the 1980 publication, Türken in Deutschland, the authors describe how they did, in fact, take the projections to schools, and they vividly recount some of the children’s observations in the classroom conversations that ensued about cultural differences between Germans and Turks and the children’s emotional responses to those differences.58

The Diaserien drew on the circulation possibilities of the literary public sphere and the public nature of sites like schools and community centers as means to generate increased discourse about Turkish minorities and their experiences in the Federal Republic. Höfer’s distribution of factual text and public projections of slides asserted the Turkish community’s established, proletarian presence in West Germany. Further, the works declared the need for increased discussion about Turkish acculturation and the need for Germans to accept their nation’s newfound multiculturalism, despite official rhetoric to the contrary and mainstream media’s methods of minority erasure.

Imi Knoebel, Innenprojektion, 1969, black-and-white photograph, 9⅝ x 11¾ (24 x 30 cm) (artwork © Imi Knoebel/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016)

Theorizing Türken in Deutschland as Counter-Publicity

Up to this point, we have been analyzing Türken in Deutschland in its aesthetic, historical, and intellectual context at the time of its creation and initial distribution. Now we turn with greater specificity to the concept of Öffentlichkeit, or the “public sphere,” revitalized in the 1960s by the Düsseldorf-born philosopher Jürgen Habermas. The term refers to the public spaces that emerged in Europe at the end of the seventeenth century, including cafes, literary salons, and print media, to facilitate broad debates about social needs, rules, and governance. Habermas argues these bourgeois public spaces and the rational critical debate produced within are necessary for the formation and maintenance of a fully democratic society, yet they withered in the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries under the force of mass media acting in complicity with advanced capitalism—an argument that aligns his work decisively with Marxist ideas of the time. Habermas laid out his claims in a 1962 book entitled Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit: Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft, which was translated in 1989 as The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society.59 His widely read text brought the concept of the public sphere to the center of debates about the postwar status of democracy in the German New Left circles of the 1960s.60

Habermas’s notion that the bourgeois public sphere was open and accessible to all gave it a radically democratic appeal. However, as Habermas admits, it ultimately failed to attain that goal and, in reality, was limited to males of specific economic classes. These limitations would eventually fall under widespread critique. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere was also initially understood as supportive of the student movement’s protests against the government and the monopolized, conservative mass media in West Germany. However, by the end of the 1960s, Habermas’s relationship with the student generation went cold, as he publicly accused student activists of producing violent and senseless “action for action’s sake” in what he called a form of “Leftist Fascism.”61 The New Left retaliated by increasingly seeking theoretical support from those outside what they considered to be the ivory tower of the Frankfurt School after Theodor Adorno’s death.62 It was from this backlash against Habermas that the concept of counter-publicity emerged.

In 1972 Negt and Kluge—Habermas’s former assistant and a key figure in New German Cinema, respectively—published an aggressive response to Habermasian theories with The Public Sphere and Experience. They advanced the concept of counter-publicity to denote the marginalized, but meaningful, discourses of those outside the dominant public sphere. Negt and Kluge’s text represented an important turning point in debates about publicity in that it allowed for the inclusion of working-class and minority groups as well as the private experiences typically understood as outside rational, democratic debate—amendments well received by the New Left. In The Public Sphere and Experience, Negt and Kluge state that the primary problem the proletariat faces is that the bourgeois public sphere “blocks” the former’s “horizon of social experience,” including the private, business, and “authentic” aspects of daily life.63 They claim that the expression of everyday proletarian experience in art, visual culture, or film is not a trivial act that stands outside civil discourse; instead, it is essential for forming an emancipatory “counter-public.” As such, Negt and Kluge’s concept of Erfahrung (“everyday experience”) gained currency throughout the decade in leftist and artistic circles.

We see a leftist interest in Erfahrung plainly in Höfer’s focus on documenting the everyday spaces and experiences of the disenfranchised West German Turks—like picnicking in parks, selling sausages in a meat shop, or casually standing with loved ones inside one’s home. By projecting such banal, working-class experiences vibrantly in public art exhibitions or distributing them to non-art audiences for display and discussion, Höfer challenged Habermas’s tightly defined notions of what was acceptable in public discourse and generated a radical counter-public in Negt and Kluge’s terms.

For German audiences in the 1970s, Höfer’s Türken in Deutschland series served as a record of the unjust fact that Turkish migrants had an established presence in West Germany without being granted citizenship or a political voice. For the photographer, the images served as an inscription of herself into the imbalanced social system of the time. The Türken in Deutschland series affirmed the artist’s 1970s ambition to record the encounter between two communities—a visual argument that ran counter to popular rhetoric, which denied the need for minority integration. When displayed as large-scale color projections or distributed as Diaserien, the images assertively called for public debate about a people rendered visually and socially taboo and asked Turkish immigrants to conceive of themselves as a visible, meaningful presence in West Germany. As such, the project was a “communicative praxis” that strove for nothing less than a counter-public in postwar West Germany: “an alternative organization of the public sphere.”64 stakes out claims for a communicative praxis, which is the basis for an alternative organization of the public sphere” (53).]

The author would like to thank Pamela M. Lee, Pavle Levi, Fred Turner, and Bryan J. Wolf for their support and feedback on earlier versions of this essay. She also thanks Candida Höfer, Michael Oppitz, and the Candida Höfer-Stiftung for sharing their time, resources, and creativity, without which this project would not have been possible.

The epigraph is from Şinasi Dikman, “Hast du das Foto gesehen?” in Wir werden das Knoblauchkind schon schaukeln: Satiren, ed. Ellen Imhof and Gisela Klump, vol. 10 of AutorenEXpress (Berlin: EXpress Edition, 1983), 59, trans. Gail Wise, “Ali in Wunderland: German Representations of Foreign Workers” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1995), 2.

Amy A. DaPonte is a teacher, scholar, and former architectural designer. Her research focuses on the history, aesthetics, and sociopolitical implications of German art in the postwar era. Current writing projects include an article on Günther Förg’s postmodern Stations of the Cross series of monotypes and sculptural panels and a book manuscript based on her dissertation, “Critical Publicity: Candida Höfer’s Public Space Photographs, 1968–present.”

- These unique publications are small booklets of text, each with a plastic cover holding twelve slides. Candida Höfer, Gudrun Wasmuth, and Elise Kentner, Alltag in der Türkei (Cologne: Vista Point Verlag, 1977); and Candida Höfer, Gudrun Wasmuth, Elise Kentner, and Hatice Özerturgut, Türken in Deutschland (Cologne: Vista Point Verlag, 1980). Yale University library has second editions of both Diaserien. ↩

- See especially Gudrun Wasmuth and Elise Kentner, “Die Bilderreihe: Begründung und Zielsetzung,” introduction to Alltag in der Türkei, unpaginated. ↩

- The leading photographer and teacher of photographic art in early postwar Germany was Otto Steinert (1915–1978). After World War II, he led the Subjektive Fotografie or Subjective Photography movement and prominently exhibited early twentieth-century Bauhaus and avant-garde photography that stressed the importance of an artist’s personal vision and means of expression over documentary-style realism. See Otto Steinert, Subjektive Fotografie: Ein Bildband moderner europaïscher Fotografie [A collection of modern European photography ↩

- See “Candida Höfer,” Guggenheim Collection Online, at www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/candida-hofer, as of September 26, 2016. ↩

- The retrospective began at the Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf as Candida Höfer: Düsseldorf, September 14, 2013–February 9, 2014, and traveled to Sean Kelly Gallery, New York City as Candida Höfer: From Düsseldorf, May 8–June 20, 2015. This was not the first time American audiences have been presented with a starkly edited vision of Höfer’s oeuvre. Starting with the artist’s first major solo exhibition in the United States, Architecture of Absence in 2005, American curators and gallerists have focused exclusively on Höfer’s celebrated interior pictures by excluding her early projects on different themes, such as Türken in Deutschland, Flipper (1973), and Liverpool (1968), even though these have appeared in European exhibitions. Graham Bader sharply criticized this American trend in his 2006 review of Architecture of Absence: Bader, “Candida Höfer: Norton Museum of Art,” Artforum 44, no. 7 (March 2006): 287–88. Yet Bader’s call that scholars consider Höfer’s early work, which challenges the continuity of her recent, beautiful, and “absent” interiors, remains largely unanswered in the United States. Exceptions include Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, which exhibited the “misfit” Zoologische Gärten (Zoological Gardens) pictures in 1993 and 2010, and LACMA’s landmark 2009 exhibition Art of Two Germanys: Cold War Cultures, which included several of the Türken in Deutschland prints. ↩

- Höfer specified to me that she does not want the images from Alltag in der Türkei published at this time. Candida Höfer, e-mail message to author, August 6, 2013. The images in the Diaserien book called Türken in Deutschland appear, however, throughout the 1979 slide show, which has been exhibited multiple times in Europe of late and was published in full in Candida Hofer, Doreen Mende, and Markus Heinzelmann, Candida Höfer: Projects Done (Cologne: Walther König, 2009), 18–61. ↩

- In fact, Bernd Becher invited Höfer to join his course after seeing the Türken in Deutschland slide show at the spring 1976 student exhibition at the Kunstakademie. The common desire of scholars to see this project as a slavish pursuit of the Bechers’ methods is clear in Astrid Ihle’s writings. Ihle describes black-and-white prints from the Türken in Deutschland series as primarily occupied with photographing “the order of things”—that is, with the “detached, cool view of an ethnologist” that defines the Bechers’ photographic “objectivity.” Ihle thus bends history to make a cohesive set of pictures taken in 1974, 1975, and 1976 examples of a method Höfer would encounter after starting the Bechers’ first photography course in fall 1976. Ihle, “Photography as Contemporary Document: Comments on the Conceptions of the Documentary in Germany after 1945,” in Art of Two Germanys: Cold War Cultures, ed. Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann, exh. cat. (New York: Abrams, 2009), 186–205. ↩

- See Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “Candida Höfer: Photography in the Public Sphere,” in Candida Höfer: Düsseldorf, ed. Gunda Luyken and Beat Wismer, exh. cat. (Düsseldorf: Richter/Fey Verlag, 2013), 46–55. ↩

- Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge, Public Sphere and Experience: Toward an Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere, trans. Peter Labanyi, Jamie Owen Daniel, and Assenka Oksiloff, Theory and History of Literature, vol. 85 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993). ↩

- In this text, I use the terms “public space” and “public sphere” distinctly. The former describes the physical places in which public discourse occurs and the latter the substance and nature of public discourse. ↩

- See Gail Wise, “Ali in Wunderland” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1995), 14. For German literature on postwar guest workers see Verena McRae, Die Gastarbeiter: Daten, Fakten, Probleme (Munich: Beck, 1981); Christian Habbe, ed., Ausländer: Die verfemten Gäste (Reinbek: Rowohlt; and Hamburg: Spiegel-Buch, 1983); Hermann Korte, Migration and ihre sozialen Folgen (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1983); Rolf Meinhardt, ed., Türken raus? oder Verteidigt den sozialen Frieden (Reinbek: Rowohlt, 1984); and Ulla-Kristina Schuleri-Hartje, Ausländische Arbeitnehmer und ihre Familien: Massnahmen im Städtevergleich (Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik, 1984). In English, see Ray C. Rist, Guestworkers in Germany: The Prospects for Pluralism (New York: Praeger, 1978); Stephen Castles, Heather Booth, and Tina Wallace, Here for Good: Western Europe’s New Ethnic Minorities (London: Pluto, 1984); Ilhan Basgöz and Norman Furniss, eds., Turkish Workers in Europe (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985); Ulrich Herbert, A History of Foreign Labor in Germany, 1880–1980: Seasonal Workers/Forced Laborers/Guest Workers, trans. William Templer (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990); Rita C. K. Chin, The Guestworker Question in Postwar Germany (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007); and Rita C. K. Chin, “Imagining a German Multiculturalism: Aras Oren and the Contested Meanings of the ‘Guest Worker,’ 1955–1980,” Radical History Review 83 (Spring 2002): 44–72. ↩

- See Herbert, 215. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Officials decided to stop the immigration of foreign workers on November 23, 1973, but the ban did not significantly reduce the number of new immigrants coming into the Federal Republic until after 1974. Rist, 63. ↩

- In 1973, the Turkish population in the Federal Republic numbered 893,000, Italians 622,00, and Yugoslavs 673,300—these were the three largest groups and the groups most likely to renew their residency visas indefinitely, but none more than the Turkish. Chin, “Imagining a German Multiculturalism,” 55. ↩

- Ibid., 9–11. ↩

- Ibid., 9. ↩

- See Chin, The Guestworker Question, 10–21. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- A notable exception is Aras Ören, whose poems were written in Turkish and translated into German for publication as early as 1973; he remains the most celebrated Turkish writer in Germany. See Heidrun Suhr, “Ausländerliteratur: Minority Literature in the Federal Republic of Germany,” in “Minorities in German Culture,” special issue, New German Critique 46 (Winter 1989): 85–88; and Aras Ören and Krista Tebbe, Morgens Deutschland, abends Türkei (Berlin: Kunstamt Kreuzberg, 1981). The latter mixes Ören’s poetry with photography of Turks by a range of German photographers and press agencies. ↩

- See Chin, The Guest Worker Question, 10. ↩

- Ibid., 3. ↩

- Wise, 5. ↩

- Arlene Akiko Teraoka, “Gastarbeiterliteratur: The Other Speaks Back,” in “The Nature and Context of Minority Discourse II,” special issue, Cultural Critique 7 (Fall 1987): 77–101. See also Marilya Veteto-Conrad, Finding a Voice: Identity and the Works of German-Language Turkish Writers in the Federal Republic of Germany to 1990 (New York: Peter Lang, 1996); and Suhr. ↩

- Teraoka, 79–80. ↩

- Ibid., 81. ↩

- Heinrich Böll, Group Portrait with Lady, trans. Leila Vennewitz (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973). ↩

- See Chin, The Guest Worker Question, 55. ↩

- In her dissertation, “Ali in Wunderland,” Gail Wise criticizes Sanders-Brahms and Fassbinder for creating foreign characters that outwardly follow stereotypes about guest workers as silent, passive, or lacking in agency; yet, she claims, there are also elements in both filmmakers’ works that potentially render those depictions farcical or otherwise highlight them as stereotypes to be reconsidered. ↩

- Oskar Negt, Alexander Kluge, and Peter Labanyi, “The Public Sphere and Experience: Selections,” trans. Peter Labanyi, in “Alexander Kluge: Theoretical Writings, Stories, and an Interview,” special issue, October 46 (Fall 1988): 72, emphasis mine. ↩

- Höfer informed me that she does not remember reading or discussing Negt and Kluge’s book for Ole John’s class but that she, like many of her academy peers at the time, was most interested in Italian neorealist and French New Wave film. Interview with the author, Cologne, October 2012. In any case, The Public Sphere and Experience was vital reading for the young, leftist intellectuals around Höfer in Cologne and at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie during the 1970s. ↩

- For more on John, who was born “Ole John Poulsen,” went by “Ole John Povlsen” in the early 1960s, and later changed his name to “Ole John,” see Peter Schepelern, “Danish Film History: 1896–2009,” trans. Daniel Sanders, website of Danish Film Institute, updated April 2010, in www.dfi.dk/Service/English/Films-and-industry/Danish-Film-History/Danish-Film-History-1896-2009.aspx, as of January 18, 2016. For a discussion of one of John’s films of a Beuys performance, see Werner Meyer, “Die Transsibirische: Betrachtungen zu Fünf Projekten: Joseph Beuys, Jochen Gerz, Raffael Rheinsberg, Sophie Calle und Günther Uecker,” Kunstforum International 136 (February–May 1997): 151–59. ↩

- The first time that I saw Türken in Deutschland was at the exhibition Der Rote Bulli at the NRW–Forum Düsseldorf in January 2011. The slide show was projected at a large scale in a small room with painted black walls, dim lighting, and a curtain separating the projection room from the rest of the white-walled exhibition spaces. As the eighty-slide sequence progressed in that small, darkened room, I had the sensation of being visually interrogated by the stream of intense male gazes cast monumentally before me. The dominating scale, repetition of strong male gazes, and affect created by cinematic installations of the slide show have yet to be addressed in scholarship. ↩

- Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Picador, 1977); and Edward Said, “The Shadow of the West,” in Arabs, a Living History, dir. Geoff Dunlop, 50 min., episode 7 of 10 (Falls Church, VA: Landmark Media, 1986), DVD. For a related critique, see Martha Rosler, “In, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography),” rep. The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography, ed. Richard Bolton (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 303–40. ↩

- See Buchloh, 48. ↩

- This is a noticeable change from her clandestine photos of Caucasian teenagers and men playing pinball in her 1973 series Flipper. ↩

- Candida Höfer and Giovanni de Riva, Conversations with Photographers: Candida Höfer Speaks with Giovanni de Riva (Madrid: Fundación Telefónica and La Fábrica, 2007), 50. ↩

- For more biographical information, see Höfer and de Riva; and Candida Höfer and Herbert Burkert, “On Projects: A Brief Conversation,” in Candida Höfer: Projects Done, exh. cat. (Cologne: Walther König, 2009), 174–75. ↩

- Michael Oppitz, interview with the author, Berlin, September 2013. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Höfer and de Riva, 57. ↩

- Höfer’s early exhibitions of Türken in Deutschland include WAS . . . not tut, Galerie Konrad Fischer, Düsseldorf, November 3–15, 1975 (solo); Nachbarschaft, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, May 21–30, 1976 (group); Türken in Deutschland/in der Türkei, Galerie Arno Kohnen, Düsseldorf, February 14–21, 1979 (solo); and Work by Young Photographers from Germany, Art Galaxy, New York, April 17–May 15, 1982 (group). See Anne Ganteführer-Trier, “Candida Höfer: Biography and Bibliography” (Cologne: Candida Höfer-Stiftung, 2011). Höfer also drafted a photobook for at least one of the slide series that was never realized; see Anne Ganteführer-Trier, “Von Anfang an: Zum photographischen Oeuvre von Candida Höfer,” Candida Höfer: Orte Jahre; Photographien 1968–1999 (Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 1999), 10. ↩

- American projection artists like Dan Graham frequently visited Düsseldorf and exhibited their work. Höfer met Graham, saw his projections and other photographic projects, and photographed him during a performance. Oppitz interview. ↩

- The historical information that follows is drawn from Scott Gerson and Lee Ann Daffner, “Harnessing Light and Motion: The Experimental Diazotypes of Otto Piene,” Book and Paper Group Annual 21, vol. 5 (2002); Otto Piene, et. al., Otto Piene: Lichtballett, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Visual Arts Center, 2011); Galerie Heseler, Otto Piene: Lichtballett und Künstler der Gruppe Zero, exh. cat. (Munich: Galerie Heseler, 1972); and Valerie Hillings, Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2014). ↩

- The influence was showcased in a recent retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s, October 10, 2014–January 7, 2015. ↩

- See Imi Knoebel, Dirk Martin, and Carmen Knoebel, Imi Knoebel: Werke von 1966 bis 2006, exh. cat. (Bielefeld: Kerber, 2007). ↩

- For more on the history of slide projection in postwar art, see M. Darsie Alexander, Charles Harrison, and Robert Storr, eds., Slide Show: The Projected Image in Contemporary Art, exh. cat. (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005); Chrissie Iles, Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art, 1964–1977, exh. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of Art, 2001); and George Baker, Matthew Buckingham, Hal Foster, Chrissie Iles, Anthony McCall, and Malcolm Turvey, “Round Table: The Projected Image in Contemporary Art,” October 104 (Spring 2003): 71–96. ↩

- Alexander, “Slide Show,” in Slide Show, 14. ↩

- Bolger, “Foreword” in Slide Show, ix. ↩

- Alexander, 22. Matthew Buckingham also argues for understanding the medium as discursive and performative; he claims that image projection creates a social space, one of conversation about the image among a group of viewers. See Buckingham text in “Round Table: The Projected Image in Contemporary Art,” 78–80. ↩

- Uwe Husslein, “Und abends in die Lichtmaschine! Das Creamcheese und die Clubkultur in Deutschland,” in Pop am Rhein, exh. cat. (Cologne: Walter König, 2008), 9–45. ↩

- Uecker, who had become a friend of Andy Warhol in 1964, wanted the discotheque to have an atmosphere akin to the multimedia events Warhol called Exploding Plastic Inevitable. Ibid. ↩

- Osborne’s participation, as well as the double projection, is described in Gislind Nabakowski, “WAS not tut,” Heute Kunst 14–15 (May–August, 1976): 27. ↩

- The exhibition did succeed in generating discourse. Höfer recently described the public’s response to the exhibition as “tremendous, so many people passing by and commenting, and rather positively in all.” Höfer and de Riva, 50–51. ↩

- Höfer and Osborne took these quotes respectively from Zeit Magazin, May 18, 1973, and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, January 11, 1974. Nabakowski, 27. ↩

- See Nabakowski, 27. ↩

- Höfer, Wasmuth, and Kentner, Alltag in der Türkei, unpaginated. ↩

- Höfer, Wasmuth, Kentner, and Özerturgut, Türken in Deutschland, unpaginated. ↩

- Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (1962), trans. Thomas Burger with Frederick Lawrence (1989; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991). ↩

- Because of the perceived urgency of Habermas’s theories in divided, Cold War Germany, he was appointed chair of the Marxist-oriented Institute for Social Research at the Goethe University in Frankfurt (seat of the “Frankfurt School”) in 1964. ↩

- See Robert C. Holub, “The Charge of ‘Leftist Fascism,’” in Jürgen Habermas: Critic in the Public Sphere (London and New York: Routledge, 1991), 90; and James Van Horn Melton, The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 3. ↩

- Holub, 90. ↩

- They continue: “The characteristic weakness of virtually all forms of the bourgeois public sphere derives from this contradiction: namely that the bourgeois public sphere excludes substantial life-interests and nevertheless claims to represent society as a whole. . . . Since the bourgeois public sphere is not sufficiently grounded in substantive life-interests, it is compelled to ally itself with the more tangible interests of capitalist production. . . . The working class must know how to deal with the bourgeois public sphere, the threats the latter poses, without allowing its own experiences to be defined by the latter’s narrow horizons.” Negt, Kluge, and Labanyi, “The Public Sphere and Experience: Selections,” 60–61, 63. ↩

- Miriam Hansen, “Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to Germany in Autumn,” in “New German Cinema,” special issue, New German Critique 24–25 (Fall 1981–Winter 1982): 36–56. She writes, “In its method and scope, [Kluge’s contribution to Germany in Autumn ↩