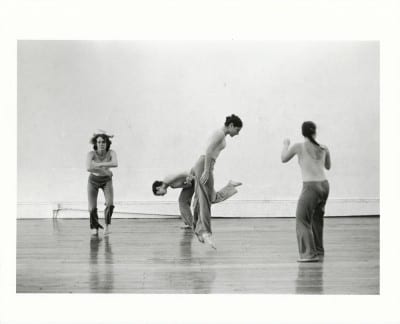

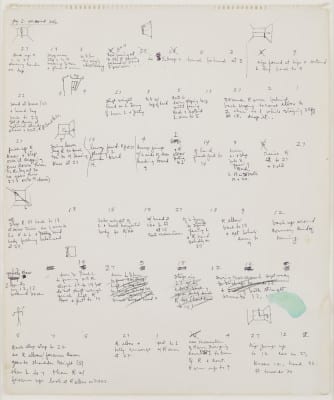

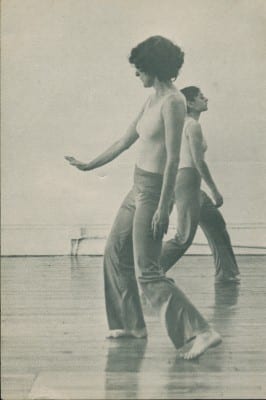

Babette Mangolte, Trisha Brown “Locus,” 1975 (photograph © 1975 Babette Mangolte, all rights of reproduction reserved) From left: Trisha Brown, Judith Ragir, Mona Sulzman, and Elizabeth Garren

In 1974 the choreographer Trisha Brown moved to 541 Broadway in SoHo, New York City. The cast-iron “nexus” for postmodern dance, commonly referred to as “the dance building,” had what the former Brown company dancer Elizabeth Garren describes as a “communal atmosphere.”1 Purchased and renovated by the Fluxus founder George Maciunas “with dancers in mind,” 541 was wider than the majority of the standard buildings in the neighborhood, and more important, it contained no interior pillars, making it an ideal choreographic work space.2 It was there that Brown conceived and premiered her 1975 dance Locus, an eighteen-minute silent work for four dancers.

Locus followed a diagrammatic score: a cube organized around numerical points, each correlating to one of the twenty-six letters of the alphabet. Located at the center of the cube, a twenty-seventh point designated the space between letters. Spelling out a biographical statement appropriated from a performance program (“Trisha Brown was born in Aberdeen Washington in 1936. She received her BA in dance from Mills College and later taught there . . .”), dancers Brown, Garren, Judith Ragir, and Mona Sulzman corporeally navigated imaginary, body-size cubes based on the choreographer’s rendering. Accounts of Locus, as score and performance, focus primarily on the work’s “mathematical,” “cerebral” process, its associations with Minimalist visual art, and its function as a pedagogical tool for transmitting a Brownian movement vocabulary.3 However, a close analysis of Locus’s formal properties and cultural context reveals that the dance is suffused with its choreographer’s “domestic reality,” her personal experience living in Lower Manhattan during a time of deindustrialization and artistic innovation.4 Indeed, to make the dance, Brown used the architectural and social space around her as an aesthetic tool. The structural constraints of Brown’s mixed-use studio at 541 Broadway were ultimately incorporated into the work’s cubic design. The present text establishes that Locus and, to a lesser degree, Brown’s 1966 dance Inside, for which she “read” the walls of her Howard Street loft as a score, are reflective of the choreographer’s pragmatically feminist spatial practice that evinces architecture’s influence on the dancing body.

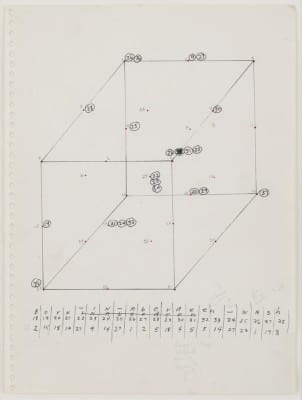

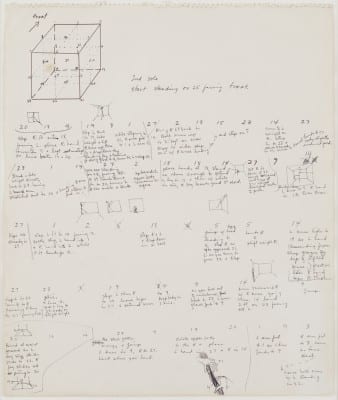

Trisha Brown, Untitled (Locus), 1975, ink and graphite on paper, 8 pages, 5 pages 12 x 9 in. (30.6 x 22.9 cm), 3 pages 17 x 14⅛ in. (43.2 x 35.9 cm) (artwork © Trisha Brown; photographs provided by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York)

Moving In

Understanding the importance of urban space to the creation of Locus means comprehending the state of New York City in the 1970s. At the time, the city was in the midst of a fiscal crisis. Municipal agencies faced extreme budget cuts. Crime and unemployment were high. The middle class had fled to the suburbs. Industrial manufacturers gradually shut down or moved their operations to more modern facilities. “The deindustrialization of New York City in the postwar period had reached its most wrenching moment,” writes the art historian and longtime New York City resident Douglas Crimp, “but some of us were unintended, temporary beneficiaries of the crisis even as others lost their jobs and homes at the same moment that social services were slashed.”5 While many New Yorkers chose, or were forced, to relocate, a small community of artists moved downtown into the abandoned, former industrial buildings. These urban pioneers, living on shoestring budgets, sought inexpensive spaces, large enough to live and work. Even as the city government all but relinquished its civic investment in Lower Manhattan, the artists collectively fashioned a sustainable creative community south of Houston Street.

This community was alive and well at 541 Broadway, where Brown lived and worked in the mid-1970s alongside many of her Judson Dance Theater and Grand Union collaborators, including Lucinda Childs, Douglas Dunn, David Gordon, and Valda Setterfield. The artist-tenants regularly attended each other’s dance concerts and social gatherings, and pitched in with the general maintenance of the building, designed by Charles Mettam and constructed in 1868. Due to their efforts, 541 changed in appearance as it did in use.6

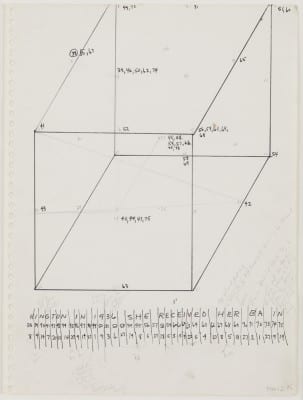

Trisha Brown, Untitled (Locus), 1975, ink and graphite on paper, 8 pages, 5 pages 12 x 9 in. (30.6 x 22.9 cm), 3 pages 17 x 14⅛ in. (43.2 x 35.9 cm) (artwork © Trisha Brown; photographs provided by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York)

Maciunas, who also owned 537 Broadway, the twin building across the courtyard from 541—home to Frances Alenikoff, Shigeko Kubota, Ay-O, Yoshi Wada, Elaine Summers, and Brown’s friend and frequent collaborator Simone Forti—was “always sensitive to the needs of his fellow artists.” When he bought 541 and neighboring 537, Maciunas knew about the buildings’ structurally forgiving floors that “would not jeopardize [dancers’] legs and feet with their jumps.”7 The dance building ultimately succeeded as such because Maciunas recognized that, as the theorist Henri Lefebvre wrote, space is ever “bound up with function.”8 In other words, the neo-Marxist cultural philosopher, who published his influential text The Production of Space in French the same year that Brown moved to Broadway, proposed that social space is not “a mere ‘frame,’” an empty “container of a virtually neutral kind,” or a thing “in itself,” but rather the product of social relations.9 In short, he theorized that people make the spaces in which they live, even as they are controlled by those spaces. To say that space is tethered to function, then, is not simply to claim that spaces are practical or utilitarian, but more precisely that spaces are practiced, produced through action and interaction.

This was certainly the case at 541, where Brown practiced sometimes competing and sometimes complementary roles: domestic mother and professional choreographer. To separate these practices, if superficially, Brown, along with many other loft dwellers, constructed a partition between her studio and living area. While the wall appeared to organize the loft into discrete areas, the choreographer openly admitted that separating her personal life from her work was nearly impossible. In fact, dividing these spheres strayed from the art-as-life principle foundational to Brown and her downtown colleagues: “We all lived in the same SoHo neighborhood, nobody had any money and we were all racing about cracking open artistic boundaries. . . . Everyone knows Allan Kaprow’s declaration that the distinction between art and life should be as fluid as possible. We were living that. There were studio visits, showings, performances and conversations at all hours.”10 Brown’s “cracking open artistic boundaries,” an acknowledgment of the permeability between art and life, is echoed by Lefebvre who, concerned with exposing the dialectics of urban space, implores us to resist the “ideologically dominant” tendency to divide “space up into parts and parcels in accordance with the social division of labour.” He asserts that even when spaces are visibly, architecturally divided they are inevitably connected by people in the midst of life activities including varied, related labor practices: “Visible boundaries, such as walls and enclosures in general, give rise for their part to an appearance of separation between spaces where in fact what exists is an ambiguous continuity.”11 This continuity existed between Brown’s studio and living areas despite the partition dividing the open floor plan.

Indeed, Brown made surface-level modifications to her space, but she inherited its fundamental geometric shape and material conditions. Her loft, like all appropriated spaces, was an architectural palimpsest. The dance critic Deborah Jowitt keenly observed the ebb and flow between Brown’s private life and work life in the loft: “Looking around [Brown’s] loft . . . I notice that the dancing half of the space has a sanded, polished floor, but that the back half—where Trisha lives with her well-beloved son Adam—still has scuffed floorboards, and in the cracks gleam pins and needles that were dropped when this was a garment-making place.”12 Brown’s neighbor, the dancer Alenikoff, recalled of the floors in her own nearby loft prior to renovation that “the floor was an obstacle course, with gaps and lurking splinters that necessitated nightly applications of gaffer tape to spare trauma to dancers’ feet and body parts.”13 Even then, in an unfinished state, the entirely wooden floors of 541 were more suitable for dance than most floors in SoHo, which were often made of concrete and covered by thin wooden floorboards. The floor alone, as Jowitt attested, revealed an overlooked archive full of rich and tactile information about SoHo’s recent past. Industrial vestiges of this past were ever present in the then newly gentrified neighborhood and inevitably contributed to its ongoing spatial production. These material remains were tangible indicators that, as Lefebvre argues, synchronic space, or “present” space, subsumes processual diachronic time. Space, simply put, has a temporal, historical dimension.14 Brown’s loft, then, was not merely a passive, accidental repository of textile-related ephemera; it was a space produced from a nexus of mostly invisible, but nonetheless consequential everyday relations performed by bodies over time.

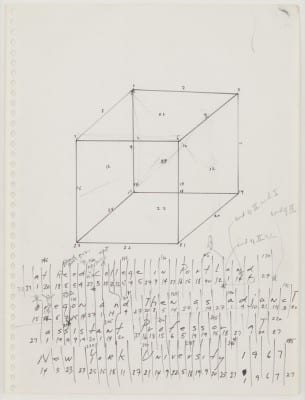

Trisha Brown, Untitled (Locus), 1975, ink and graphite on paper, 8 pages, 5 pages 12 x 9 in. (30.6 x 22.9 cm), 3 pages 17 x 14⅛ in. (43.2 x 35.9 cm) (artwork © Trisha Brown; photographs provided by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York)

With regard to the ongoing social production of SoHo, these relations precipitated the historically significant shift from commodity production (textiles) to creative production (art and dance). Addressing art and cultural production, the economic urban policy scholar Elizabeth Currid notes, “The places where such [creative sector] goods are created, distributed, and consumed have become critical nodes of culture as well, and they too are becoming commodified and mass produced.”15 When Jowitt visited Brown at 541 in 1974, she witnessed a place that was fast becoming a product. Between the rough “back half” of Brown’s loft and the smooth “dancing half,” the reporter—who was really much more interested in how dance fit into the city’s changing economy than she was in the specifics of Brown’s floor renovations—detected the major spatial transition well under way. Through her related observations about the interior modifications to the loft at 541, the presence of the physical remnants of industry, and downtown artists’ fluid movement between varied forms of labor, and between art and everyday life (if such a distinction exists), she outlined a spatiotemporal history of Lower Manhattan, with Brown’s loft at its locus.

Inside Out

In 1965, nearly a decade prior to her move to 541, Brown lived in a second-floor loft on Howard Street.16 At the time, Brown’s son was a baby, and due to her maternal responsibilities and limited income she found herself totally housebound. Brown recalls that she was only able to continue to pursue a career in dance because one of her students offered to trade instruction for childcare. Brown’s early Lower Manhattan loft on Howard Street, similar to her later loft on Broadway, was a space in which the young choreographer and mother’s “professional and domestic spaces interpenetrated one another,” as they did her dances.17

Brown’s dances of this period have been regarded as “autobiographical.”18 Like a good autobiographer, Brown took creative liberties in how she told her own story. To make Inside, a three-minute solo that premiered at the Judson Memorial Church in March 1966, Brown first “read” the walls of her home loft as a score and afterward translated this score into an abstract, idiosyncratic series of movements that was at once evacuated of and laden with her “domestic reality.”19 Although Brown later considered Inside “juvenilia,” her improvisational, architecturally activated process illuminates how she used her everyday surroundings as source material, thus anticipating her 1975 dance Locus.20

Trisha Brown, Untitled (Locus), 1975, ink and graphite on paper, 8 pages, 5 pages 12 x 9 in. (30.6 x 22.9 cm), 3 pages 17 x 14⅛ in. (43.2 x 35.9 cm) (artwork © Trisha Brown; photographs provided by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York)

Brown began her preparations for Inside at an approximately twelve-foot distance from her loft’s messy, postindustrial perimeter: dead exposed wires, uneven drywall, a fire escape, her young son’s toys scattered about. Moving from the “extreme left” to “far right” of each of the four walls in her studio, one after the other, Brown studied the perimeter’s surface and contents. She then created an “odd distribution of actions and gestures” based on what she saw. When she visually encountered a broken window, for instance, she extended her arm, bent it at the elbow, crooked her wrist forward, and methodically zig-zagged her flat, stiff hand, palm down, through the air, from eye level to waist. Brown called this process “read[ing] the wall as a score.”21 She borrowed this technique from her friend and contemporary Forti, who proposed (and performatively illustrated) that anything, and anyone, could be considered a score.

Brown recalls that Forti would sometimes begin her “rule games” by pointing around a room “in a blind way.” “If you got [or pointed to] a window,” Brown continues, “you could say the dance should be done in four sections, and no one section has more weight than any other section, and the floor of the room should be divided into four parts.”22 The “pointer” decided on the score, but the score—in this case, the window—determined elements of the improvisational danced response. Architectural features and objects supplied choreographic information: the number of sections the dance should have, which section was to have more weight, or how the dance space should be separated. Formal characteristics like proportion and material composition helped dancers generate spontaneous, interpretive actions that neither mirrored nor mimetically reproduced the score. The physical surroundings, much like the graphic notation that had emerged in experimental music of the 1950s and 1960s, offered “a means to compose a structure.”23 That structure, or the related components of the dance, in turn disclosed something about the limits of loft space that generally remained otherwise overlooked.

Trisha Brown, Untitled (Locus), 1975, ink and graphite on paper, 8 pages, 5 pages 12 x 9 in. (30.6 x 22.9 cm), 3 pages 17 x 14⅛ in. (43.2 x 35.9 cm) (artwork © Trisha Brown; photographs provided by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York)

When Brown created Inside she was similarly interested in discovering the rules inherent in “the live space, the surface of [her] working space.” By drawing on her “actual environment” rather than “some illusory, theatrical world” she infused her dance with her own reality, one that through her chosen score implicitly reflected her own surroundings.24 Comprising the “collection of alcove, door, peeling paint and pipes,” among other loft elements, the score for Inside was physically inseparable from its site.25 As such, Brown drew on what I call an architext, or a choreographic score determined by elements in her live-work space. The “text” in architext is here derived from Brown’s description of her corporal response as a reading of the walls of her loft as a score. I also employ the word “text” because I find it helpful to conceive of Brown’s proposal in terms of Roland Barthes’s claim that the text (as opposed to what he calls the work) has an intrinsic interpretive openness; in other words, texts can be read in many ways.

On this particular occasion, Brown’s architext was not only explicitly site-specific but also site-dependent. Brown’s intimate space became her score in part because she knew it habitually, but wanted to more fully comprehend its objective presence. Filled with a bustle of inanimate action due to age, wear, use, and its former industrial identity, the loft provided a tangible rawness that Brown wished to embody. Brown’s piece was thus about a particular kind of unsettled urban domesticity, one that the choreographer and many of her friends experienced living in their architecturally and economically liminal neighborhood.

The 1966 dance concert at Judson Church included Brown’s piece Inside; however, at that time the dance was, notably, titled Outside. Marianne Goldberg indicates that Brown changed its name after the Judson performance, but before she performed the piece at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the NOW Festival in Washington, DC. Goldberg argues that the “vacillation between Inside and Outside as the title seems entirely appropriate: Brown transformed the interior of her home into a surface that catalyzed a dance that then traveled out into the public sphere. The loft that inspired Brown’s improvisations was not a conventional, private-sphere apartment but a place still full of the traces of public, industrial activity.”26 Illuminating as Goldberg’s comments on the shifting spatial dynamic of Brown’s loft are, she stops short at explaining why the dance was called Outside in its premiere at Judson—a familiar venue, within walking distance of Brown’s loft—and subsequently titled Inside when presented in venues outside the city and the community that the choreographer called home.

Brown may have initially believed that her dance—a choreographic distillation of the embodied response she had to the walls of her loft—moved with her from her loft’s interior outside, to the public performance space in Judson’s sanctuary. Yet as she performed she came to realize that the dance did not move with her, but inside her. She had internalized the movement so completely that it “felt concretely specific” to her but appeared “abstract to the audience.”27 As the choreographer moved along the inner edges of the rectilinear seating configuration that mirrored the geometry of her loft, the details of her movement and its off-site source were veritably illegible. When, for example, Brown reached upward with her whole body and afterward dove down, nearly skimming the sitting viewers’ knees, few would have supposed she was reacting to a massive rust stain and some dispersed wires. In these moments, it no doubt became clear to Brown that her performance was too personal and specific to exist outside its relation to her body. It was inside her, and even after its public performance, remained there, beautifully inscrutable and ever bound to Brown’s muscle memory.

Trisha Brown, Untitled (Locus), 1975, ink and graphite on paper, 8 pages, 5 pages 12 x 9 in. (30.6 x 22.9 cm), 3 pages 17 x 14⅛ in. (43.2 x 35.9 cm) (artwork © Trisha Brown; photographs provided by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York)

In her Village Voice review, the critic Jill Johnston focused on Brown’s infallible “presence,” a hallmark of all of her performances.28 By emphasizing Brown’s presence, Johnston (understandably) skirted an analysis of the dance’s self-consciously abstract content. This content, albeit present on (and within) Brown’s dancing body, was contingent on absence. To illuminate how absence operates in Insidelet us turn to the art historian Rosalind Krauss’s discussion of the index as it relates to dance. Krauss observes that “within the convention of dance, signs are produced by movement.” Dance movements, in other words, traditionally convey meaning; in ballet, and in most modern dance, they enhance narratives and communicate feelings and ideas. They thus exist within the realm of the symbolic. In Brown’s dance, movement is not symbolic. Her dancing body is rather a register of something outside itself, as Krauss further notes, “a circumstance that is registered upon it (or, invisibly, within it).” The choreographer-cum-dancer performatively manifests a trace of the absent architext, which functions here as what Krauss calls an index, “a type of sign which arises as the physical manifestation of a cause.”29 The index, as such, is physically visible and present in the dance, but its source is spatially and temporally remote and thereby publicly illegible. The remoteness of the architext makes it all the more significant. The dance exists because Brown performed it outside the place where she made it, a place where her site-specific, site-dependent architext would continue to exist. Brown’s performative “presence” is thus contingent on her loft’s absence, but it is also indicative of the fact that Brown, who had internalized her “domestic reality” as “concretely specific” movement, felt right at home wherever her dance traveled.

Outer Space

Nearly ten years after Brown “read” the walls of her Howard Street loft, she drew the score for her 1975 dance Locus. “Part fabrication model, part document, and part independent artwork” the graphic score, like Inside’s architext, offered “a means to compose a structure.” 30 It was a tool kit to design and organize the pieces of the dance composition, which were sometimes fixed and at other times variable. This diagram, first privately published in a pamphlet titled Trisha Brown/A Profile, marked a transition in how Brown made scores, and in how she read them.31 Rather than turning to her outside environment for dance limitations, Brown drew on self-imposed limitations that she created through a choreographic framework.

Trisha Brown, Untitled (Locus), 1975, ink and graphite on paper, 8 pages, 5 pages 12 x 9 in. (30.6 x 22.9 cm), 3 pages 17 x 14⅛ in. (43.2 x 35.9 cm) (artwork © Trisha Brown; photographs provided by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York)

In the case of Locus, this framework was premised on an alphanumeric cube that began on the page but would invisibly and three-dimensionally occupy the space of her studio. While Locus did not respond to an architext per se, its score and the contingent dance did “relate . . . to the floors and walls” where Brown and her young company rehearsed and premiered the work.32 The architectural restrictions inherent to Brown’s 541 Broadway loft indeed informed the choreographer’s spatially economical approach. Thus, Locus, often regarded as a purely formal, even minimalist, pedagogical dance experiment, is by all means imbued with a plainly feminist pragmatism, one as spatial as it is social.

To make the score for Locus, Brown drew a cube and marked it with twenty-seven points. A letter of the alphabet was assigned to each of these points. Point 1 located in the upper left corner of the cube is “A,” 2 on its upper middle edge “B,” and so on. The space between letters is designated point 27, situated in the cube’s center. Brown then chose a piece of biographical text that she “found” in a dance program. She copied it onto the page in upper-case letters, removed the punctuation, and inserted graphite lines between each letter. The “simple biographical data” became, in her hand, a “neutral” alphabetic sequence:33

T/R/I/S/H/A/ /B/R/O/W/N/ /W/A/S/ /B/O/R/N/ /I/N/ /A/B/E/R/D/E/E/N/ /W/A/S/H/I/N/G/T/O/N/ /I/N/ /1/9/3/6/ /S/H/E/ /R/E/C/E/I/V/E/D/ /H/E/R/ /B/A/ /I/N/ /D/A/N/C/E/ /F/R/O/M/ /M/I/L/L/S/ /C/O/L/L/E/G/E/ /A/N/D/ /L/A/T/E/R/ /T/A/U/G/H/T/ /T/H/E/R/E/ /S/H/E/ /H/A/S/ /A/L/S/O/ /T/A/U/G/H/T/ /A/T/ /R/E/E/D/ /C/O/L/L/E/G/E/ /I/N/ /P/O/R/T/L/A/N/D34

By pairing letters in the arbitrary writing sample with corresponding numbers on the cube to create a sequence, Brown attempted to evacuate her score of subjectivity. “All I wanted,” Brown claims, “was a sequence of numbers.”35 This sequence of numbers was derived from a selection that, according to Brown, served merely as random advice, and operated solely as an ordering agent.

Brown’s pursuit of neutrality was flawed, as the curator Hendel Teicher suggests, because the text “shows an interest in the subject.” Brown ultimately concedes to the trace subjectivity in her selection. “All scores are imperfect in my experience,” she confesses, “But this [the score for Locus] was a beginning.”36 The score for Locus, then, is both a step toward neutrality and a recognition that neutrality may not exist. It is an effort to eliminate subjectivity and a method of demonstrating that it is impossible to completely divorce art from artist. The neutrality Brown sought with her score, if fallible, was as political and social an effort as it was an aesthetic one, inspired by a nexus of influence. It was indicative of a trend in much New York avant-garde dance of the 1960s and 1970s that attempted to break free of the theatrics and emotion associated with modern dance. “Neutrality,” as Sally Banes writes, “was a refreshing antidote to the emphasis on virtuosity and psychological expression.”37 While many downtown dancers experimented with everyday (pedestrian) movement, Brown’s interest in creating neutral scores echoed that of the experimental composer John Cage, whom the choreographer consistently cites as her greatest influence.38

Trisha Brown, Untitled (Locus), 1975, ink and graphite on paper, 8 pages, 5 pages 12 x 9 in. (30.6 x 22.9 cm), 3 pages 17 x 14⅛ in. (43.2 x 35.9 cm) (artwork © Trisha Brown; photographs provided by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York)

Brown was introduced to Cage’s approach by Robert Dunn, who taught composition classes for dancers and artists in the 1960s. Dunn, who had been Cage’s student at the New School for Social Research, encouraged his own students, Forti, Yvonne Rainer, and Steve Paxton among them, to experiment with a variety of compositional “methods” (procedures), “materials” (content), and “structures” (the whole as parts).39 Cage, for one, often used chance methods to determine the structure of his compositions. He rolled dice, flipped coins, and arranged a performance based on the imperfections in paper. With these operations, Cage could consign decision-making authority to a source outside himself, thus evading artistic ego.40 For his 1951 piano solo Music of Changes, Cage used the sixty-four hexagrams in the Chinese “Book of Changes,” the I Ching, to create charts determining aspects of the composition including tempo, duration, pitch, timbre, and silences.41 Chance was not only meant to eliminate subjectivity, it was also designed to imitate nature, in the process, opening up the work to unforeseen possibilities.42

From Cage, Brown learned that scores were a means of simultaneously relinquishing and maintaining control of the work. The cube was also an instrument for striking such a balance. Brown chose the cubic form for its ability to impose limits while promoting new movement possibilities. She recalls, “I wanted to create a sphere of personal space, but I couldn’t get a grid out of the sphere, so I turned it into a cube and numbered it.”43 Rudolf Laban, pioneer of modern dance and spatial analysis, and an innovator in dance notation, inspired Brown’s initial choice of the sphere. Laban had developed his own dance sphere, the “kinesphere,” that he similarly described as the “personal space” around the body.44 Unlike the kinesphere, which was primarily a means to record all the possible movements of the body, Brown’s cube-as-score compelled particular, idiosyncratic, Brownian movements that would, eventually, become the DNA for her dances. To be clear, the kinesphere was a movement map, the dancer’s figure consistently located at its center. Brown’s cube, on the other hand, was rendered as an empty armature, both its geometry and the numerical points that decorated it generating constraints.

Although the points on Brown’s cube were relatively fixed (she admits to moving them around in order to precipitate more visually pleasing geometrical gestures), the dancers’ bodies and their movements were not. Her instructions for Locus note, “There are opportunities to move from one cube to another without distorting the movement. By exercising these options, we travel.”45 Brown’s dancers could move into and out of their cubes, between cubes, and across their imaginary grid, a structuring agent that they could manifest whenever and wherever they saw fit. Accordingly, Brown’s cube promotes a spatial agency of sorts, one in line with Brown’s improvisational, makeshift method and aesthetic. Alternately, the kinesphere, as its name implies, invariably moves with the dancer, his center of gravity its veritable anchor. The purpose of Brown’s cube was not to portray human movement comprehensively, nor to preserve it. On the contrary, she wanted to see (and feel) how movement would organically change over time and space given a particular set of restrictions.

Unknown videographer, still from Locus, 1975, video, shot at Mills College, 1977, sound, 14 min. 12 sec., from 2-DVD set Trisha Brown Early Works 1966–1979 (New York: ArtPix, 2005)

Brown’s cube is also significant because of the form’s art-historical associations and its contemporaneous deployment by mostly male sculptors. The curator Donna De Salvo notes, “Within the modernist paradigm” the cube had “come to represent a utopian ideal.” It stood for more than order; it was a form designating a higher order: an absolute. The cube was literally a space outside everyday space, distinguished and defined by opposition. However, as De Salvo further argues, the artists who “turned to the cube” during the 1960s and 1970s did so “to complicate it.” In their hands the cube underwent a transition. “Clinging to these identifiable structures, artists introduced something else to the system; the disorder and contradictions of the world.”46 The Minimalist sculptors of the period, including Mel Bochner, Donald Judd, and Sol LeWitt, made reflexive cubes, “primary structures” that compelled an awareness of “the gallery itself” and the viewer’s “body existing within this ambiance.” In the cube, the art historian James Meyer writes further, the Minimalists found “a form so basic that it did not have to be invented, so standard that it did not reflect the artist’s personal decision-making.”47 Indeed the cube “did not have to be invented,” but it did have a long history of being reinvented. Minimalist cubes signaled a departure from the absolutist modernist ideal. Brown’s imaginary dance cubes conceptually and formally deviated from both.

Unlike the cubes fabricated by her artist contemporaries, Brown’s were not made from plywood, glass, or metal. Arguably, they were not made at all. Brown’s cube, rendered by the choreographer’s hand as the basis for her diagrammatic score, and envisioned by the dancers in Locus for the length of the performance, was ephemeral and reproducible. As an invisible, durational form, the cube in Locus lacked the hard, “masculine” edges, corners, and angles of the material cubes, often interpreted as “aggressive” and “cold.”48 Brown’s cube was, quite literally, handmade, in that it was activated by touch, its bounds made visible through the gestures of dancing bodies. Unlike the male Minimalist artists who sent “their drawings or ‘blueprints’ out to be translated into three-dimensions by other people,” Brown and her dancers produced the artist’s cubic vision in house, as their audience watched.49 That being so, there was a transparency not only to Brown’s cube itself, but also to the labor that went into its production. Not only did Brown and her dancers produce their cubes, their bodily movements became, over the course of their dance, the material from which their cubes were derived. Never an entirely reified or recognizable structure, Brown’s cube was made from movement and produced over time. As production rather than product, the Brownian form highlighted the physical labor of its makers, who worked at creating personal and collective space in which to move, rather than art-market commodities.

Unknown videographer, still from Locus, 1975, video, shot at Mills College, 1977, sound, 14 min. 12 sec., from 2-DVD set Trisha Brown Early Works 1966–1979 (New York: ArtPix, 2005)

Although there were significant artistic differences between Brown and her male contemporaries, and between Brown’s cubes and theirs, the choreographer was consistently “identified with minimalism in the public’s mind and eye.”50 Brown, however, did not identify as a Minimalist, and in fact resented the designation. Voicing exasperation, perhaps on Brown’s behalf, the New York Times critic Jack Anderson penned a 1979 article, paradoxically titled “Trisha Brown’s Minimalism,” in which he sought to differentiate Brown’s often whimsical, consistently embodied fascination with “rigorous structural principles” from that of the artists for whom the (albeit often faulty) classification was more appropriate: “And because she disdains theatrical frills and prefers a no-nonsense kind of movement, she may be called a ‘minimalist.’ . . . But, oh dear, how dull that makes her sound, and she is anything but dull. Perhaps, then, it might be better to find some other way to describe her. Brown herself has even given a clue as to how one might go about it. Significantly, on one occasion she defined herself as ‘a bricklayer with a sense of humor.’”51 The choreographer’s “bricklayer” self-identification indicates that the work of dance requires a blue-collar perseverance, more often associated with industry than with art. Moreover, Brown’s choice of brick as metaphorical material suggests her artistic cooptation of everyday, preexisting “found” forms, neither sleek, nor expensive. Not entirely unlike the brick, Brown’s cube was sensible and durable. She chose it not because of its affiliation with Minimalism, but, at least in part, because of its spatial economy and adaptability.

Brown’s loft at 541 had limited performance space. The four performers in Locus could have, under a different choreographic circumstance, overwhelmed this space, the dimensions of which proved a challenge for dancing, as for watching. “Even though the loft [at 541] was 35 feet wide,” Brown remembers, “the stage we use[d] [wa]s 28 feet deep, so I could only get seven feet back from my work. My head was constantly swinging back and forth.”52 Garren recalls that the dancers in the quartet, bound to their cubes, were hardly “moving through space” but somehow they nonetheless received “critiques of being too expansive.”53 Her comment parallels an observation by none other than Brown’s choreographic predecessor, Merce Cunningham, who was one of the first to challenge the spatial traditions of classical dance staging: “If you don’t divide a space classically, the space remains more ambiguous and seems larger.”54 Together, and separately, the dancers in Locus produced a space that appeared larger than it was in reality. The cube’s invisible, dancer-manifested limits conserved space even as its cubic structure, as Sulzman recalls, “open[ed] up the dance by suggesting the possibility of multiple facings.” Brown had created a revolving dance. Following in Cunningham’s choreographic footsteps, Brown’s piece challenged the conventional notion that dances should have a front and back; “any of the four surfaces (but not the floor or overhead surface) may be considered the front.”55 Brown’s cube was a solution to a spatial problem, one reflective of the constraints Brown faced living and working in her loft. It showed her awareness of the art-historical role of the cube, but was equally a practical invention, indicative of Brown’s particular set of architectural, economic, and social conditions.

Space Travel

Locus was shot on video, but perhaps not “captured,” in 1977 at Mills College. The video begins with Brown, Garren, Sulzman, and Ragir, dressed in loose white muslin drawstring pants and leotards hand-dyed with tea, facing different directions. Their preliminary actions mark the beginning of the first of the dance’s three sections that together, Sulzman explains, “highlight the relationship between seminal form and extended structure and offer the viewer a sampling of the material and its possibilities.” During the first section, about ten minutes in length, the dancers perform “in unison, and have the option of changing cubes and facings at any time.”56 In synchrony the women jump, kick, stretch their arms, swoop their legs, and plunge. Lucidly and with precision, the dancers in their cubes—their cubes in a three-dimensional grid, five units wide and four deep—bend and bow, look up and lunge. The anonymous videographer who remains in one position for the course of the performance, zooms in slowly so that the dancers fill the frame and the space of the studio beyond their imaginary grids falls away. A few minutes in, the camera pans slightly right, then slightly left, before gradually zooming out into a wide shot. But for this exception, the frame moves very little. From a single location in the room, the static lens determines the front of the dance, even when the dancers ignore it. Thus, there is a disjuncture between, on the one hand, the dancer and dance that temporarily unhinges orientation, and, on the other, the videographer and video that permanently hinge it.

Unknown videographer, still from Locus, 1975, video, shot at Mills College, 1977, sound, 14 min. 12 sec., from 2-DVD set Trisha Brown Early Works 1966–1979 (New York: ArtPix, 2005)

The strained “spatial relationship” between the recording and the dance, and between performing and watching more generally, reveals what Erin Brannigan calls “problems of visibility and legibility”; “dance has a tendency toward unrestrained, hyperbolic motility and unexplained stasis which challenges video tendency to order, restrain, frame, and cut.”57 But the apparently unedited recording of Locus does more than contain or bridle movement; it determines perspective, imbuing Locus with one front. From his or her stationary position, the videographer, most likely ignorant of the importance of the dance’s changing orientation, demonstrates that capturing the nuances of Locus is impossible. Yet the camera’s stasis is reflective of the experience of the live spectator, who, from his or her fixed seated position, misses the dancers’ revolving movements.58

It is not only the video that is in conflict with Locus then, it is immobility itself. Watching a dance from a single, fixed perspective forces the viewer to examine the tension between stillness and movement, and the agency that mobility provides. It also distances the experience of the viewer from that of the performer, exacerbating the space between inside and outside, and demonstrating that this space is created by knowledge as much as it is by physical location. In spite of, or perhaps because of, the distance between spectator and dancer, the viewer, as Marcia B. Seigel writes of her 1976 experience of Locus at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, perceives the dance as a “whole.” From afar, the audience watches the dance’s “design” unfold. While the dancer focuses moment by moment on how and where her body moves through space, the audience sees the big picture. The dancers and their gestures transform into fluid patterns of “harmonious sets of diagonals” “getting created and erased very quickly.”59

Within these grand fluctuations in form, the dancers make a transition from the first to the second section, in which they “activate the same points in space in the same order, with different movement.”60 Now they are allowed to choose their movement vocabulary from Brown’s homemade gestural language, visually and kinetically reminiscent of yoga and tai chi. The quartet’s calm, meditative actions during this part of the dance include handstands, floor rolls, and straight-back bends. Each of the women strings her individual movements together without transitions, enhancing the dance’s fluidity. There are no highs and lows, no energy bursts or lulls. All of the dancers’ actions—in the second section of the piece, and throughout—are presented with equal weight. By the third and final section of the dance, the dancers have earned “so much” improvisational “freedom” that the section can never “be repeated in the same form” twice.61 The dance concludes with the performers facing different directions and executing different movements at different times. Their gestural and directional autonomy allows them to move more quickly than they did during the first two sections, and with new ease. In this final section of Locus, the dancers pick and choose the movements they want to revisit from the earlier sections. Here, dancers make autonomous decisions that give rise to “an unforeseen situation.”62 The performative indeterminacy, like the chance method that Brown employed to create her score, is a Cagean means of relinquishing choreographic control and opening up the dance to otherwise unexplored possibilities. In this case, the dance becomes “an open system” filled with brief relational intersections.63

Postcard for Trisha Brown Company at Brooklyn Academy of Music—Lepercq Space, 1976, b/w offset printing on card, front and back, 6 x 4 in. (15.2 x 10.2 cm) (photograph © Babette Mangolte; images provided by Mona Sulzman) From left: Trisha Brown and Mona Sulzman

One such instance in the video version of Locus occurs when Garren’s arm arches around Sulzman’s waist. Less of an interaction than two actions overlapping, the dancers’ separate but interconnected movements illustrate the dance’s poetic contradiction: actions and reactions are at once autonomous and connected. Sulzman writes, “Self-containment in Locus does not preclude a kinesthetic oneness among the four dancers, even if we do not look like we are relating to one another. In fact, a large part of the fascination and difficulty in performing this dance springs from the peculiar state of split concentration that is as much a part of the piece as is the movement.”64 Echoing Sulzman’s comments, Garren recalls, “You were in your own cube, but you were spatially aware of how you were related to one another.”65 Both dancers describe a feeling of simultaneous interdependence and independence that contributed to the overall success of the dance, which unfolded “in time and space” because “four people together came to a rhythm but it wasn’t a standard rhythm.”66 Without music (or a common musical tempo) to lead them, the four moved in and out of unison as they moved in and out of their cubes, and through the larger grid network. Like “basketball players” who must rely on their “peripheral vision” to gauge the actions of their “teammates,” the dancers developed a shared “pulse.”67 Locus, then, is a performance demonstrating the inner workings of a community. It is a kinetic portrayal of relationships in continual flux and a social system that existed both on the dance floor and off.

From the outside, the dance’s methodical and precise engineering, and even the space inside the construction, is completely invisible. A testament to the power of frameworks that go unseen, the beauty of Locus’s structure is contingent on its invisibility. For in Locus, structure is the product of faith, of blind belief in a collective vision. Sulzman herself argues, “Knowledge of how Locus works is not a requisite for enthusiastic response to the piece . . .”68 Anderson expressed a similar sentiment. “Puzzling over structure,” he noted, “can be part of the fun of watching the dance.”69 From its exterior, and even from within, Locus is, as the critic Jennifer Dunning contended, “more pleasurable than process.”70 In fact, for the spectator, there is pleasure in never completely knowing the process behind the dance or seeing the scaffolding that holds it together.

The dynamic among the dancers in Locus is compelling, given its social and historical context. It was the first dance Brown, Garren, Sulzman, and Ragir practiced and performed together, and the premiere dance for Brown’s new company, founded in 1974. After Brown’s first company—primarily comprising her nondancer friends—disbanded in the early 1970s, the choreographer recruited trained dancers with natural athletic ability. While she was still committed to a nonvirtuosic aesthetic, with Locus Brown “wanted to make a dance full of rich and complex movement—something [she] had not done in almost twelve years.”71 To accomplish such a dance and in the process to “transfer her own highly complex, technically-advanced and innovative improvisational moves” to her new dancers, Brown and the women worked all day every day for months.72 Brown acknowledged, “Locus . . . is technically very difficult to do, and I couldn’t ask a non-dancer to hold his or her leg up for four counts.”73 Therefore, Locus marks a change in how Brown trained her dancers, the kinds of dances she choreographed, and the type of dancers she recruited.

The premiere of Locus at 541 is significant for its dancers, who, with the exception of Brown, were all new to Lower Manhattan. A transplant from Vancouver, Sulzman moved to the city in August 1974. She joined Brown’s nascent company after about six weeks of classes with the choreographer. Brown recruited Garren and Ragir, friends from Minneapolis, not long afterward.74 The women, who were simultaneously excited and intimidated by the “grubby turned-on” Manhattan of the 1970s, navigated their new city as they did the cubes in Locus.75 For, like Locus, Manhattan was, to borrow Rem Koolhaas’s description, “at the same time ordered and fluid . . . a metropolis of rigid chaos.”76 The city was geographically and architecturally structured to at once promote isolation and alienation and to provide countless and regular social encounters, jostling its residents into a heightened awareness of their environment. As the dancers mastered moving within the parameters of their imaginary cubes, and through the three-dimensional grid that the cubes generated, they became adept in traversing the unpredictable city grid. In and outside the studio, the women learned to negotiate their personal space, directing and redirecting themselves with poise and purpose.

Postcard for Trisha Brown Company at Brooklyn Academy of Music—Lepercq Space, 1976, b/w offset printing on card, front and back, 6 x 4 in. (15.2 x 10.2 cm) (photograph © Babette Mangolte; images provided by Mona Sulzman)

However, the limits that the women faced as dancers living in New York during the 1970s were reliant on more than the city’s built environment. All three performers, who had little to no savings, lived on tight budgets; their choices were reflective of their economic constraints. They walked (or, at night, ran) home rather than taking a cab, shared crowded loft spaces, and saved up to split a bowl of spaghetti at Fanelli Cafe on Spring Street.77 In 1975 the Wall Street Journal reporter Roger Ricklefs painted a picture of dancers’ New York City experience, dominated by financial difficulties. His humorously but accurately titled “For Art’s Sake: Field of Modern Dance Booms, but Performers Struggle to Survive, Subheading: Even Biggest Names Earn Little but Revel Instead in ‘Inner Satisfactions’/Wheat Germ up in the Lofts” took a necessarily dramatic tone: “Until only a few years ago, modern dance was mainly considered an esoteric art form, appealing to a few devotees. In those days, it might be expected that modern dancers would eke out the barest of existences. Today, however, the field thrives on a scale that few of its early pioneers ever imagined—and the people who make it all happen barely survive.” To prove his point with concrete numbers Ricklefs added that “no more than 15 modern dancers in the country earn more than $10,000 a year from their dancing.”78 The dancers’ meager incomes, however, fostered a resilient, communal atmosphere. In veritable poverty, the women in Brown’s company came to depend on one another for resources and support. Their rigorous practice schedule and shared social network cemented their bond, apparent in their first performance of Locus and every rendition thereafter.

When Brown and her company danced Locus for the first time at 541, the choreographer considered it a work “in progress.”79 The dancers were still “discover[ing] [their] own movement capacities,” and Brown was adding, subtracting, and manipulating sections of the choreography. By dancing Locus in different environments—early on at Artpark in Western New York, later at the American Dance Festival hosted by Connecticut College, and in its maturity in 1976 at the LePercq Space in the Brooklyn Academy of Music—the quartet illustrated that while the dance began in a loft, its cubic form a reflection of Brown’s limited studio space, the dance and the “portable” space it articulated could travel.80

Trisha Brown, Locus Solo, 2011, performed by Diane Madden in “Performance 11: OnLine/Trisha Brown Dance Company” in conjunction with the exhibition On Line: Drawing through the Twentieth Century, Museum of Modern Art, New York, January 2011 (photographs © Yi-Chun Wu; photographs provided by Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY)

Like most dances, Locus “outgr[ew] the womb” of its practice space. While studios, as Sulzman states, “influence . . . dance-making and even future performances of all dances somewhat (after all, they are the choreographer’s and dancers’ second or even first home and workplace),” they are spatial cocoons that dancers and dances shed if the dance is to have legs.81 Forged, but not permanently housed, by the spaces in which they were created, dances move, like the dancers who perform them, and “movement,” as Laban noted “leads to growth and structure.”82 The dancers in Locus created and re-created their gridded infrastructure wherever they performed, thereby demonstrating that the relational grid, and its aesthetic projection, is as dependent on producers as it is on places.

Disregarding a dance’s origin, the place of its inception, and the cultural and architectural specificities of that place, is just as dangerous as neglecting its spatial malleability and relational resilience. After a 1977 performance-demonstration of Locus in the theater at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, the SoHo Weekly News critic Wendy Perron, who danced with Brown’s company from 1975 till 1978, expressed nostalgia for a more informal and visually egalitarian dance space. She bemoaned, “Perhaps because I had previously seen this piece in a loft setting, which I think of as its natural habitat, it seemed adversely affected by being shown on a proscenium stage. The imaginary cubes through which the dancers move were distorted by the perspective lines and spatial hierarchies that the proscenium stage imposes on material placed within its bounds.”83 Perron’s complaint, while legitimate, was as motivated by emotion as by architecture. Though Perron, as a dancer, must have known that dances move with their dancers, that a dance is always contained by the changing architectural or environmental space(s) where it is performed, and that Locus, as a dance that revolves, caused “seeing difficulties” no matter where it was performed, she still longed to see the piece in its “natural habitat.” Apparently resentful of the proscenium’s “spatial hierarchy,” Perron’s comments suggest that she was attached to the social affect of the loft space at 541 Broadway as much as she was to the place itself. But how could she verbalize this? How could she parse her feelings and experiences of the space from the physical environment? How could she separate feeling from structure when they were one and the same?

Trisha Brown, Locus Solo, 2011, performed by Diane Madden in “Performance 11: OnLine/Trisha Brown Dance Company” in conjunction with the exhibition On Line: Drawing through the Twentieth Century, Museum of Modern Art, New York, January 2011 (photographs © Yi-Chun Wu; photographs provided by Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY)

Struck with a new case of nostalgia, Perron, in a January 19, 2011, Dance Magazine blog post, “The Big Picture of Trisha Brown,” gives a glowing review to a solo version of Locus, danced by the Brown company’s rehearsal director, Diane Madden. The dance, included in a program celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Brown’s company and performed in conjunction with the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition On Line: Drawing through the Twentieth Century, was, according to Perron, the highlight of the program. In her response to the piece, which hardly resembles the 541 Broadway version of 1975, given that in the 2011 solo Madden is, of course, the lone dancer, and hers is the only invisible cube, Perron writes that “what I found most moving [of all the dances in the MoMA program] was the piece in a tiny area. Diane Madden performed a solo version of Locus (1975) in a small, outlined square of space. . . . It’s all about Trisha’s very original sense of architecture of the body and its continuity. Locus was the dance I watched most often during the three years I was with Trisha. The other dancers used it to warm up, and I feel like I’d come home every time I see it (though I was never in it).”84 From outside Madden’s square, marked by blue tape on the museum’s floor, Perron enters a space of memory. As Madden extends her arms and lifts her leg, connecting invisible points in space, Perron mentally connects all of the places and moments in time in which she watched Locus. In so doing, she claims to “come home.” Here, Perron’s home—the familiar space she inhabits when watching Locus—like the cube that Madden constructed at MoMA and the grid that Brown, Sulzman, Garren, and Ragir created multiple times before that, is invisible. But, as Brown’s choreographic architecture for Locus attests, resilient structures often remain unseen: completely intangible and concretely felt.

For Mona Sulzman, who thinks on her feet.

I am grateful to Douglas Crimp, Robert Doran, Rachel Haidu, and Joan Saab, who read an early version of this essay when it was a rough-and-tumble dissertation chapter; their perceptive comments motivated me to reconsider the body’s relationship to space. Susan Manning, Joanna Dee Das, and Jennie Goldstein read later, more developed, incarnations of this essay and suggested valuable additional sources and helpful revisions. Their consummate generosity is remarkable, and I am a better scholar for it. Alison D’Amato fielded my last-minute questions on Rudolf Laban; I appreciate her easy and unpretentious expertise. Jenevive Nykolok, Gloria Kim, and Ryan Fitzsimmons were exceptional sounding boards; they always ask the right questions at the right times. Former Trisha Brown dancers Elizabeth Garren, Judith Ragir, and especially Mona Sulzman were my patient interlocutors. Mona’s 1978 article “Choice/Form in Trisha Brown’s Locus: A View from Inside the Cube” in part inspired this analysis of Brown’s dance. Without Babette Mangolte’s photographs and films and videos of Brown’s dances, my research would have no eyes. Sneha Shah, Robbi Siegal, Scott Briscoe, Cherry Montejo, and Northwestern Library’s Repository and Digital Curation staff helped me obtain illustrations. Stephanie Frontz directed me to a variety of useful reference materials. My archival research was funded in part by Mellon Dance Studies and the Raymond N. Ball Dissertation Fellowship. Finally, I am ever grateful for the challenging and insightful reviews I received from this essay’s anonymous readers.

Amanda Jane Graham is the Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Dance Studies at Northwestern University, where she teaches between the departments of dance and art history and the Kaplan Institute for the Humanities. She has a doctorate in visual and cultural studies from the University of Rochester. Her current book project examines dance in American art museums since the 1930s.

- The arts producer John Killacky called the building a “nexus of postmodern dance history” in an interview with Andy Moore, October 26, 2008, available as a podcast at “Andy’s Treasure Trove,” Episode 8, at www.andystreasuretrove.com/, as of April 11, 2016. The Elizabeth Garren quote is from my phone interview with her, February 17, 2012. ↩

- See Richard Kostelanetz, Soho: The Rise and Fall of an Artists’ Colony (New York: Routledge, 2003), 78. ↩

- See Lorrain Haacke, “Trisha Brown: Dancing Naturally,” Dallas Times Herald, April 11, 1976, 6; Jennifer Dunning, “At Play in the Fields of Terpsichore,” Dance Magazine, March 1976, 39; Peter Eleey, “If You Couldn’t See Me: The Drawings of Trisha Brown,” in Trisha Brown: So That the Audience Does Not Know Whether I Have Stopped Dancing, ed. Eleey (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2008), 23; Susan Rosenberg, “Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art,” October 140 (Spring 2012): 19; and Megan V. Nicely, “The Means Whereby: My Body Encountering Trisha Brown’s Locus,” Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts 10, no. 4 (2005): 58–69. ↩

- Trisha Brown quoted in Marianne Goldberg, “Reconstructing Trisha Brown: Dances and Performance Pieces: 1960–1975,” (PhD diss., New York University, 1990), 129. ↩

- Douglas Crimp, “Action around the Edges,” Sixteenth Annual David R. Kessler Lecture, CUNY Graduate Center, New York, November 2, 2007; rep. Mixed Use, Manhattan: Photography and Related Practices, 1970s to the Present, ed. Lynne Cooke and Crimp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 98. ↩

- See City of New York, Landmarks Preservation Committee, “SoHo–Cast Iron Historic District Designation Report (New York: Landmarks Preservation Committee, 1973), 44. ↩

- Both quotes from Kostelanetz, 78. ↩

- Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1991), 94. ↩

- Ibid., 93–94. ↩

- Trisha Brown in Lydia Yee, “All Work, All Play: In Conversation with Laurie Anderson, Trisha Brown, Jane Crawford, RoseLee Goldberg, and Alanna Heiss at the Clocktower Gallery, New York, 27 September 2010, “ in Laurie Anderson, Trisha Brown, Gordon Matta-Clark: Pioneers of the Downtown Scene, New York 1970s, ed. Yee (London: Barbican Centre, 2011), 69. ↩

- Lefebvre, 89–90. ↩

- Deborah Jowitt, “Trisha Brown Makes Dances That Talk Back,” Village Voice, January 12, 1976, 110. ↩

- Frances Alenikoff quoted in Kostelanetz, 79. ↩

- Lefebvre, 110. ↩

- Elizabeth Currid, “Bohemia as Subculture; ‘Bohemia’ as Industry: Art, Culture, and Economic Development,” Journal of Planning Literature 23, no. 4 (May 2009): 369. ↩

- In her interview with Klauss Kertess, Brown recalls that she made Inside while living on Franklin Street; in conversation with Marianne Goldberg, however, Brown claims she lived on Howard Street while preparing for the performance. Because she performed Inside in a joint Judson Church dance concert with her Howard Street third-floor neighbor Deborah Hay, I am choosing to reference the latter street. Kertess interview; and Goldberg. ↩

- Goldberg, 127. ↩

- Ibid., 138. ↩

- Trisha Brown quoted in Goldberg, 129. ↩

- Brown quoted in Rosenberg, 27. ↩

- Kertess interview; and Anne Livet, “Trisha Brown: Edited Transcript of an Interview with Trisha Brown,” in Contemporary Dance: Anthology of Lectures, Interviews, and Essays, ed. Livet (New York: Abbeville, 1978), 48. ↩

- Brown quoted in Sally Banes, Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1987), 78. ↩

- Marianne Goldberg, “Trisha Brown, U.S. Dance, and Visual Arts: Composing Structure,” in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961–2001, ed. Hendel Teicher (Andover, MA: Addison Gallery of American Art, 2002), 34. ↩

- Goldberg, “Reconstructing Trisha Brown,” 44. ↩

- “Chronology of Dances,” in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961–2001, 301. ↩

- Goldberg, “Reconstructing Trisha Brown,” 128. ↩

- Livet interview, 48. ↩

- Jill Johnston, “Hay-Brown,” Village Voice, April 7, 1966, 13. ↩

- Rosalind E. Krauss, “Notes on the Index: Part 2,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myth, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986), 211. ↩

- Rosenberg, 40. ↩

- Author interview with Mona Sulzman, Ithaca, New York. January 29, 2012. Sulzman printed the Locus diagrams in her “Choice/Form in Trisha Brown’s “Locus”: A View from Inside the Cube,” Dance Chronicle 2, no. 2 (1978): 119; there she cites “‘Trisha Brown/A Profile,’ a pamphlet privately printed by L & S Graphics.” Livet printed a selection of the diagrams in her 1978 anthology Contemporary Dance. ↩

- Haacke, 4. ↩

- Hendel Teicher, “Danse et Dessin/Dancing and Drawing: Trisha Brown–Hendel Teicher: entretien/interview,” in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961–2001, 17. ↩

- Sulzman, 119. ↩

- Teicher interview, 18. ↩

- Ibid., and Brown quoted in ibid., 17. ↩

- Banes, 95. ↩

- See, for example, Haacke; and the Kertess interview. ↩

- Sally Banes, Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater, 1962–1964 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 5. ↩

- See John Cage, “Composition: To Describe the Process of Composition Used in Music of Changes and Imaginary Landscape No. 4,” in Silence (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961), 59. ↩

- The literature on Merce Cunningham and Cage’s use of chance procedures is extensive, and even those texts that do not specifically reference chance operations by name discuss choreographies and compositions based on chance. For a comprehensive list of sources on Cunningham and Cage, see “Selected Bibliography,” in Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years, ed. David Vaughn (New York: Aperture, 1997); Vaughn, archivist of the Cunningham Dance Foundation, provides commentary in the book. While writing this essay, I consulted primary sources by Cage as well as “Notes on Cunningham Choreography,” in John Cage, Writer: Previously Uncollected Pieces, ed. Richard Kostelanetz (New York: Limelight, 1993); Richard Kostelanetz, Merce Cunningham: Dancing in Space and Time (London: Dance Books, 1992); and Merce Cunningham and Jacqueline Lesschaeve, The Dancer and the Dance: Conversations with Jacqueline Lesschaeve (New York and London: Marion Boyars, 1991). ↩

- See David Revill, The Roaring Silence: John Cage—A Life (New York: Arcade, 1993), 91. ↩

- Teicher interview, 18. ↩

- Rudolf Laban, The Language of Movement: A Guide Book to Choreutics (Boston: Plays, Inc., 1966), 10 ↩

- Brown’s instructions in Sulzman, 118. ↩

- Donna De Salvo, “Where We Begin: Opening the System, c. 1970,” in Open Systems: Rethinking Art c. 1970, ed. De Salvo (London: Tate Publishing, 2005), 1. ↩

- James Meyer, Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 161 and 22. ↩

- Ibid., 227. ↩

- Clement Greenberg, “Changer: Anne Truitt,” in Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, Modernism with a Vengeance, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 289. The essay first appeared in Vogue, May 1968. ↩

- Trisha Brown, with Susan Rosenberg, “Forever Young: Some Thoughts on Selected Choreographies of the 1970s–1990s Today,” November 14, 2009, at www.trishabrowncompany.org/?page=view&nr=745, as of April 7, 2016. ↩

- Jack Anderson, “Trisha Brown’s Minimalism,” New York Times, July 15, 1979, 18D. ↩

- Brown quoted in Tony Phillips, “Dancing about Architecture: Judith Jameson and Trisha Brown are Moving In,” Village Voice, December 3, 2002, at www.villagevoice.com/news/dancing-about-architecture-6412025, as of April 7, 2016. ↩

- Garren interview. ↩

- Cunningham quoted in Cunningham and Lesschaeve, 20. ↩

- Sulzman, 124. ↩

- Ibid., 125. ↩

- Erin Brannigan, Dancefilm: Choreography and the Moving Image (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 126. ↩

- Mona Sulzman relayed that the audience at 541 sat in five rows of chairs along one wall of the studio. The dancers I spoke with, Corrie Ollinhouse, and ArtPix (which released the video on DVD) do not know who operated the camera for the Mills video. ↩

- Marcia B. Siegel, “Brown Studies,” SoHo Weekly News, January 15, 1976, 26. ↩

- Sulzman, 126. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- John Cage, “Indeterminacy,” in Silence, 36. ↩

- Sulzman, 126. ↩

- Ibid., 128. ↩

- Garren interview. ↩

- Sulzman interview, 2012. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Sulzman, 122. ↩

- Anderson, 18D. ↩

- Jennifer Dunning, “At Play in the Fields of Terpsichore,” Dance Magazine, March 1976, 39. ↩

- Haacke, 4. ↩

- Teicher interview, 38. ↩

- Brown quoted in Jean Nuchtern “Accumulating Trisha Brown,” SoHo Weekly News, January 8, 1976, 24. ↩

- Author interviews with Sulzman and Garren. ↩

- Jowitt, 110. ↩

- Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (New York: Monticelli Press, 1994), 20. ↩

- These were but a few of the many cost-cutting measures that Sulzman and Garren recounted in their interviews. ↩

- Roger Ricklefs, “For Art’s Sake: Field of Modern Dance Booms, but Performers Struggle to Survive, Subheading: Even Biggest Names Earn Little but Revel Instead in ‘Inner Satisfactions’/Wheat Germ up in the Lofts,” Wall Street Journal, January 9, 1975, 1. ↩

- Nuchtern, 24. ↩

- Mona Sulzman, e-mail correspondence with author. January 29, 2012. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Laban quoted in Irmgard Bartenieff, Body Movement: Coping with the Environment (New York: Gordon & Breach, 1980), 1. ↩

- Wendy Perron, “When the Wind Is High: Trisha Brown at Pratt Institute,” SoHo Weekly News, March 10, 1977, 16. ↩

- Wendy Perron, “The Big Picture of Trisha Brown,” Dance Magazin January 29, 2011, at dancemagazine.com/news/The_Big_Picture_of_Trisha_Brown__/, as of April 7, 2016. For more on the MoMA performances, including an excerpt from the solo Locus, see “Performance 11: On Line/Trisha Brown Dance Company, Jan 12–16, 2011,” at www.youtube.com/watch?v=_NSrJypk6QE&feature=related, as of April 7, 2016. ↩