Shana Lutker, Shana Lutker: Le “NEW” Monocle, Chapters 1–3, installation view, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC, October 29, 2015–February 15, 2016 (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Cathy Carver)

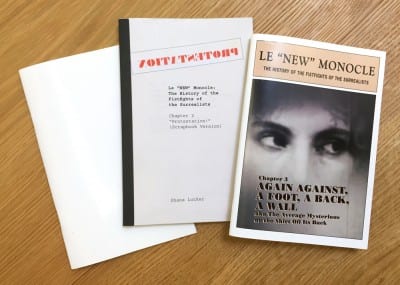

Mika Yoshitake: Le “NEW” Monocle, Chapters 1–3, your project that was recently on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC (October 27, 2015–February 16, 2016), focuses on three (out of a total of eight) historical fistfights between Surrealist artists that occurred in the mid-1920s. The project has three components: an essay comprised of your research with elaborate footnotes, a physical installation with sculptures and objects drawn from your archival research, and a performance based on the details of the fistfights themselves. Each component informs the other, and the overlaps create additional narratives from which viewers genera te their own connections about the objects and fragments that appear in the stage sets or the texts.

Shana Lutker: In some ways, it seems obvious—different kinds of information need to be relayed in different ways. I’m interested in how a viewer has a physical experience with an object, beyond or outside language. It can be emotional and psychological. It’s a way to access the unconscious or to trigger it, using strategies to evoke the uncanny. By placing things next to each other and creating relationships of scale and of texture, it puts the viewer in a certain state of play. That’s how the objects engage.

Yoshitake: They operate like props, too.

Shana Lutker, Chapter 1: The Bearded Gas, 2013, installation view, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC, October 29, 2015–February 15, 2016 (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Cathy Carver)

Lutker: The central question was how to tell these stories of the fistfights? It seems clear the best way to do that in historical detail is through writing, which I really enjoy. It’s a way to follow through on multiple threads, layering the history with my anecdotes and digressions.

Yoshitake: And the coincidences that you encounter in the process.

Lutker: Each one of the eight chapters expands on a moment—a fistfight where somebody hit somebody else—but it opens up, weaving together the past and present, art and biography.

Shana Lutker, Chapter 2: Protestation!, 2014, installation view, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC, October 29, 2015–February 15, 2016 (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Cathy Carver)

Yoshitake: In addition to your project, there has been a resurgence in contemporary reconsiderations of the historical avant-garde, especially Surrealism, since the exhibition The Encyclopedic Palace at the 2013 Venice Biennale in the Giardini’s Central Pavilion. The Encyclopedic Palace began with Carl Jung’s The Red Book (1914–30) and Breton’s death mask (c. 1950) by René Iché, symbolically positioning these as axis points for postwar art. Simultaneously, there has also been a rise in performance-based practices. While your project isn’t necessarily about performance, there are elements that are very performative, such as the way in which you present the objects on actual theatrical sets with a reflective mirror in the back. I’d like to hear about the stage sets and how they get reconfigured in different spaces. At the Pérez Art Museum Miami, for example, where you first exhibited Chapter 3, the stepped platform was configured differently from the way it was installed at the Hirshhorn. You’ve mentioned that each iteration of the project is like recalling a dream.

It made me think about my own research into the 1970s Japanese movement Mono-ha (School of Things). Even though the same objects—they would never call their work sculpture—would be presented over and over again, the artists (Lee Ufan in particular) were interested in presenting structures that allow for a renewal of perception. Each work has been referred to as a one-time “finite encounter,” which would be repeatedly displayed and composed of a different spatiotemporal experience. While there is a clear historical reference in your case, and they’re not as completely abstract as the Mono-ha works, I do see a resonance with how you present your objects—the display tables in particular.

Lutker: I like that idea, and I also think about the encounter, the specific time and place that a viewer sees the work. Each time it happens, the objects are the same, yet a little bit different. It’s interesting that you point out that the Mono-ha artists would never call their work sculpture. I still have a hard time saying that word. I didn’t train as a sculptor, and “sculpture” implies that one is making objects for the sake of making objects—things that are stable.

Yoshitake: There’s a sense of permanence.

Shana Lutker, Bureau of Research, 2013, two pieces of steel, each 7 x 20 x 1 in. (17.7 x 50.8 x 2.5 cm) (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Robert Wedermeyer)

Lutker: That’s something that I hope to undermine. While I undeniably make things that are singular “sculptures!,” sometimes even with very traditional materials like bronze or granite, I tend to jump around between materials and techniques to avoid stability. In past work, I avoided the heaviness of “sculpture” through photographing my objects and exhibiting the photos, or, as in the table display pieces, by mixing found and made objects so that the distinction between them becomes unimportant. I can see clearly now that installing my objects for the Chapters in these “stage spaces” or “stage sets” creates a sense of impermanence or potential movement. Props are placed temporarily and the mirrors amplify movement. It’s as if you turned around fast enough, the sculptures might shuffle around, like actors on a stage.

Yoshitake: Can you describe how the performative elements operate the project?

Lutker: Each Chapter has a performance or live element. Both the performances for Chapter 1 and 3 (the ones that I’ve presented publicly so far) were opportunities to incorporate and present the primary artworks that were pivotal in these fistfights. With Chapter 1, for example, the associated play, which was a Performa 13 commission titled The Nose, the Cane, the Broken Left Arm. I told the story of the fistfight of July 6, 1923, via a narrator. The play is driven by his lecture. As part of the narrator’s talk, he showed the films by Man Ray, Charles Sheeler, and Hans Richter, and a pianist accompanied them with compositions by Erik Satie, Igor Stravinsky, and Darius Milhaud—all were part of the program on the night the fistfight happened.

Shana Lutker, Shana Lutker: Le “NEW” Monocle, Chapters 1–3, installation view, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC, October 29, 2015–February 15, 2016 (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Cathy Carver)

Yoshitake:There several recurring symbolic elements the Chapters. What is the significance of the diamond cutout in the Chapter 2 stage set, for example?

Lutker: The reference is to construction sites. Especially in New York, which is where the set for Chapter 2 was first installed at the 2014 Whitney Biennial, big construction sites have plywood all around the excavations, lining the sidewalk. The plywood often has these diamond-shaped holes cut in the plywood for windows or air circulation.

Yoshitake: I never realized that.

Lutker: In my installation, these cutouts function as a surprise, an interruption in the mirror that’s reflecting the viewer’s gaze. The same thing happens when you’re walking in New York next to these plywood walls, which are often painted a dark green or blue. All of a sudden there’s this jarring break, where you see through to the building site.

Yoshitake: Like breaking the fourth wall.

Lutker: And, coincidentally, the Romeo character in the ballet that is referenced in that group of works, Chapter 2, had a black diamond painted over one of his eyes.

Shana Lutker, detail of New Research Concerning the Fistfights of the Surrealists, 2012, The Center for Ongoing Research & Projects, Columbus, Ohio (artwork © Shana Lutker)

Yoshitake: There is a certain tactility that occurs in the process of translating historical drawings or designs from your research into material objects. Can you talk about transforming the drawings by Max Ernst and Joan Miró into actual objects, such as the stainless steel mobile dancers?

Lutker: Deciding on materials is often an intuitive, fast decision. There’s a skirt shape in one of the Miró drawings, and I immediately saw it as a sculpture in felt. For the steel mobile, I directly traced Miró’s costume drawings into vector files on the computer, and had the shapes laser-cut from polished stainless steel.

Yoshitake: I was first drawn to your work through the dream objects that you began making around 2004, before the Surrealist fistfights. I felt there was an affinity with “speculative objects,” works that do not follow sculptural conventions and cannot be confined to art-historical categories. This idea was at the core of my permanent collection exhibition at the Hirshhorn, Speculative Forms (2014–16). The genesis of this project took place when we were looking at objects together in the Hirshhorn’s sculpture storage in the fall of 2014, and our interests converged. Can you talk about that moment? How would you describe your engagement or approach to objects?

Shana Lutker, The Average Mysterious and The Shirt Off Its Back, 2015, performance, May 7, 2015, Pérez Art Museum Miami (artwork © Shana Lutker)

Lutker: I’ve never used the word speculative in relation to my work, but it’s so good. The first definition I found online for speculative is to be “engaged in, expressing, or based on conjecture rather than knowledge.” “Conjecture” is not quite right––it tilts to the negative, the opposite of knowledge. This openness that you mentioned is, in my opinion, a positive thing. To be in a speculative state means that there are options, different sides to the same coin. It can allow for various ways to engage and associate with or to these objects.

In your process of combing the Hirshhorn’s collection for the Speculative Forms exhibition, you started with a premise that couldn’t be articulated before you started actively looking. Rather than organizing the works chronologically, or by geographic or cultural affinities, you discovered connections between these objects in their materiality, or formal repetition—coincidences in their objectness through the process of looking.

Yoshitake: For Speculative Forms, I concentrated on rarely displayed objects from the early twentieth century to the present that foreclosed binaries such as figurative versus abstract, still versus kinetic, and volumetric versus stereometric. Each selected work oscillates between two states and allows for a formal and conceptual openness, an idea that is also foundational to both Surrealism and your own work. There are indeed formal connections: the head-like repetition of the Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, and Juan Hamilton in the show, for example. This type of formal repetition comes across in your table displays too.

Lutker: You weren’t necessarily expecting to find that repetition. It’s not in your hypothesis; it comes out through the process.

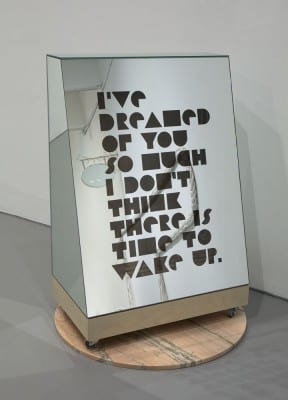

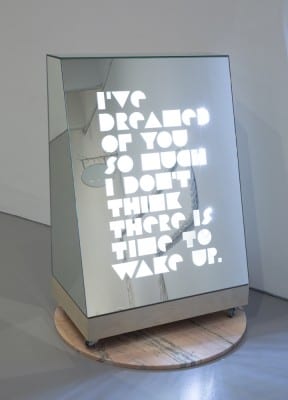

Shana Lutker, A handsome confused puppet, 2015, mirrored glass box, fluorescent lights, wood, marble, casters, 49 x 30 x 19 in. (124.4 x 76.2 x 48.2 cm) (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Cathy Carver)

Yoshitake: The connections actually happened during the installation process when the works were placed within the space. I think it also relates to this great Georges Didi-Huberman quote you have about representation.

Lutker: “Representation, in the Freudian economy notably, does not ‘reproduce’ an object (an object of desire): it produces its absence, and animates its loss.”1

Shana Lutker, A handsome confused puppet, 2015, mirrored glass box, fluorescent lights, wood, marble, casters, 49 x 30 x 19 in. (124.4 x 76.2 x 48.2 cm) (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Cathy Carver)

Yoshitake: What you bring to the object as an artist is not necessarily the same as what I would as a curator. There is a kind of loss or incompleteness in the existence of the object in the mind of the other. That’s a core idea that can inform your objects or the object displays, and the way that you approach production. There are always multiple layers of meaning or interpretation that happen. They’re not fixed. Returning to the definition of speculative, for my exhibition, I drew in part from speculative realism—the philosophy of thinking about materialism and realism, a nonhierarchical way of treating these objects—and, more specifically, the triadic relationship created among the viewing or artistic subject, the sculpture itself, and the space.

For example, what happens when we see Constantin Brancusi’s Torso of a Young Man (1924), a modernist sculpture with immense historical value, with Juan Hamilton’s Untitled (1975), a worn, pebble-like bronze? While each plays on anthropomorphic abstraction, there is a collapsing of hierarchical values established by medium or genre. When looking at your selection of things, both found and fabricated, a similar leveling occurs.

Lutker: That brings us back to the tables in the Hirshhorn exhibition, #research (Chapters 1–3) (2016), and the leveling that happened there. I made loose arrangements of things, sentences so to speak, from my accumulated research archive: historical images of found objects, snapshots taken with my phone, pieces of junk on the ground. They were brought, literally, onto the same plane—the table—to be seen for their commonalities. The differences were not as important in these arrangements, as with your selection process for Speculative Forms. It’s about the relationships, the commonalities that exist—in spite of the differences.

Shana Lutker, #Research (Chapter 2), 2015, 42 x 28 x 21 in. (106.6 x 71.1 x 53.3 cm) (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Cathy Carver)

Yoshitake: Unintended affinities happen.

Lutker: These table arrangements convey how I think about history. Lately, I revel much more in the ways humans are consistent, the same as in the past. These table displays convey those traits, in a way. When I’m looking at the history of Surrealism, moments that occurred ninety years ago, what gets my attention are the things that make me feel closer to that time and allow for a leveling of the playing field. Humans have been human for so long! The same desires, the same insecurities, the same fistfights, the same shapes and materials. It’s just mediated by different technologies.

Yoshitake: For you, it’s not necessarily about simply mining the historical past, but making sense of it through the contemporary moment. Can you talk about the origins of Le “NEW” Monocle?

Lutker: The title Le “NEW” Monocle references both the past and the present. A monocle implies looking with one eye, or that what one eye sees is in clearer focus than the other. It means your perspective is off or different—incomplete.

Shana Lutker, detail of #Research (Chapter 2), 2015, 42 x 28 x 21 in. (106.6 x 71.1 x 53.3 cm) (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Cathy Carver)

Yoshitake: Lopsided, maybe.

Lutker: Yes, or one-sided.

Yoshitake: Then there is the doubling of the spectacle—the fistfight—too.

Lutker: Also, inserting the English word “New” into the French is like me: the female American artist, inserting myself into this history, butting in. It’s my monocle for looking back at history as I want to, with one eye still in the present. It doesn’t feel like a splitting or doubling but rather an in-betweenness, being in two places at once. Finally, Le “NEW” Monocle is also the name of a bar that exists on the site where one of the fights happened in Paris. The fistfight ignited because Robert Desnos, who had been kicked out of the Surrealist group, opened a bar in Montparnasse called Bar Maldoror, named after Comte de Lautréamont’s 1874 novel Les Chants de Maldoror, which Breton referred to frequently as a foundational text of Surrealism. A bar in Breton’s view was a base thing, not an acceptable place to spend your time, because drinking and dancing are foolish. Opening a business is capitalist, an entrepreneurial impulse. In short, Surrealists shouldn’t open bars. Even though Desnos had already been kicked out, it was an offense for Desnos to evoke Surrealism in the naming of his bar.

In the week before officially opening, the bar hosted a banquet for a Romanian princess. The Surrealists decided to crash the party. They showed up, stormed in, smashed the doors, knocked the tables over, and broke bottles. It was a bloody fight with a lot of broken glass. Bar Maldoror didn’t last very long. It became a famous lesbian bar in the 1930s called Le Monocle.

Shana Lutker, Centre Real Ism, 2014, hand-painted aluminum LED light box sign, 22 x 32 x 4 in. (55.8 x 81.2 x 10.1 cm) (artwork © Shana Lutker)

Yoshitake: Was there cross-dressing?

Lutker: In photos I’ve seen taken at the bar, there were a lot of women dressing in men’s clothing.

Yoshitake: Wearing the monocle as a motif?

Lutker: Exactly. Then, Le Monocle closed. Over time, it changed hands and names quite a few times. Several years ago, it opened as Le “NEW” Monocle. The name recalls the famous 1930s bar, but it doesn’t add up. The current bar, with dancing girls, bottle service, and big Eastern European bouncers, is far from the first iteration of Le Monocle. Not long after I discovered that Le “NEW” Monocle was on the site of Bar Maldoror in Paris in 2012, I felt it was the right title for this book and body of work.

Yoshitake: How did you choose the fights and their order?

Lutker: In 2011, I was reading Mark Polizzotti’s Breton biography, Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton, making notes of things as I read. I became interested in the pervasive violence, the violence between artists and the resulting fistfights—it surprised me. I made a list of all the fights that Polizzotti mentions that were specifically instigated because the definition of Surrealism was being established or defended. Each incident centers on a protest or interaction between groups of artists, activists, or communists where there was some pushback. These altercations were subsequently reported in newspapers or in a memoir by a supposedly objective bystander, so it was not all just from Breton’s point of view.

An image from Lutker’s research for the exhibition: Mark Polizzotti’s Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton, 2012

Yoshitake: Within Surrealism, the most infamous divide is between Breton and Georges Bataille. From an art-historical standpoint, that major split happens in 1929 (La Révolution Surrealiste versus Documents). This story is set earlier, during the shift from Dada to Surrealism.

Lutker: I’m deliberately focusing on Breton’s definition and his attempt to establish Surrealism as a philosophy, a way of living and way of making art in the world. There are other groups or individual artists who we now understand as having Surrealist tendencies, qualities, and associations, but Breton is the one who established the Surrealists as a group with strict definitions of who could be in or out. One reason Breton is generally accepted as the founder of Surrealism is due in part because he stayed with it. Also, his reliance on Freud and psychoanalysis to help define the unconscious is something I relate to. Early on, Louis Aragon was involved, and he and Breton did a lot of the early writing together. At some point in the late 1920s, Aragon chose Communism over Surrealism. Bataille represents another side of Surrealism, however, as Bataille wasn’t trying to establish a group per se. Yvan Goll did try to establish Surrealism as a movement in the early 1920s. There was an editorial battle in the various periodicals in which Goll was trying lay claim to Surrealism over Breton, but in the end, Breton won and took historical possession.

Yoshitake: I’m thinking about the split and Bataille’s base materialism, which has informed much of our reading of art, from Abstract Expressionism to post-Minimalism to abject art, versus Breton, which perhaps for you stems more from a biographical read.

Lutker: It’s about structure. Breton was building a structure for the practice of allowing unconscious thought to infiltrate lived experience. It’s a fascinating juxtaposition: the unconscious or irrational and its governance. Breton was all about rules. He was a bureaucrat. You had to show up to the Surrealist meetings everyday at 4:00 p.m. and drink whatever he told you to drink. Applying this structure to the irrational is a contradictory move and followed Freud’s attempt to establish rules of analysis. In a previous body of work, I did research on J. M. Charcot and the supposed invention of hysteria in the late nineteenth century. Charcot established a framework and protocol, listing and delineating the symptoms of hysteria so that they could be treated—structure to madness.

Breton, Freud, and Charcot were trying to invent ways of identifying and interpreting the unconscious through scientific method. I relate to this sense of remove and the analytical, much more than to André Masson or other Surrealists who wallowed in madness. I’m more into the function of repression, distance, and translation—strategies humans develop to deal with trauma or desire, rather than diving head first into the unconscious and abandoning one’s grounded self.

Yoshitake: While your current research on the Surrealists has been your focus since 2011, the strategies and methods you use in this project have through lines linking back to some of your earliest works. In the Dream Book, 2003 (2004) and the dream house House 1986–1996 (2005), you methodically dated and recorded the contents of your dreams over a three year period and constructed a print archive of these accounts presented in bound volumes that use the font, layout, and headline styles of the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. These stories became the source for a series of objects that you made and installed into a model of a house.

Lutker: The house was modeled on the one that I grew up in, which I reconstructed from memory.

Yoshitake: There are layers of retrieval that you’ve built into these structures, whether it is the book or the house. It’s not self-analysis, but that process seems to have helped you think about how to create objects in the Surrealist fistfights project.

Lutker: Looking back at the dream project, I can see that I was building an archive, establishing an index by pulling some things out of the archive, and using that as a script to generate sculptures and objects.

Yoshitake: Does that relate to the research processes with which you’re currently engaged?

Lutker: Yes, that structure and process is still at the foundation of how I work, and how I present that work. I started by doing archival research in Paris and other places, amassing images, texts, associated objects, and ephemera, and identified the parameters for an index that acts as an organizational tool for the “inspiration” to make objects. The structure allows me to make the decisions or reveals the relationships between things in a way that is similar to what we did when we looked through the Hirshhorn’s storage. In my view, I am making composites or models of things rather than creating or inventing new things. I need to be immersed in the research process to find the source material, and only then can I jump into making an object.

Yoshitake: Why do you actively eschew the act of making or fabricating? There is an interesting linguistic slippage between fabrication as a means of materially producing something, as well as fabricating fictions or non-truths.

Lutker: Everything comes from somewhere, right? In a Freudian way, I feel like I’m just a conglomerate of images and experiences of the past that have come together in this present. The things I make come out of that.

Yoshitake: Rather than presenting your works as autobiographical, you are a conduit.

Lutker: In both the dream project and the history of the Surrealists, I want to foreground my role as an active agent—but not as a creator, more as a conduit with a perspective.

Yoshitake: There’s a humor in the work, especially when one reads the titles of the objects, such as The Thingy and Its Hat (2012), Mr. My-God (2012), and Handsome Confused Puppet (2015). The moment when your humor is perceived or realized by the viewer reflects a shared exchange much in the way laughter is a shared condition.

Lutker: Humor reminds the viewer that these are not authoritative or objective objects. While they refer to and draw from history, they remain subjective.

Yoshitake: I’d like to talk about the role of gender. Marvelous Objects (October 29, 2015–February 15, 2016), the Surrealist sculpture exhibition that was concurrently on view on the same floor of the Hirshhorn, included Alberto Giacometti’s Woman with Her Throat Cut (1932). Such misogynistic or violent imagery recurred throughout the show. Your project is about fistfights, but it is also about violent acts by male proponents. For you, is there a motive behind how, as a feminist, you are telling these stories in the present? How does gender come into play here?

Shana Lutker, As Many Versions as Witnesses, no. 1, 2015, wood (ash), table position: 29 x 51 x 51 in, (73.6 x 129.5 x 129.5 cm), chair position: 64 x 51 x 21 in. (162.5 x 129.5 x 53.3 cm) and Shana Lutker, Ambassadors or Poets, 2015, ceramic, dimensions variable (artworks © Shana Lutker; photograph by Robert Wedermeyer)

Lutker: Gender is always at play in my work. Fistfights are examples of a specifically gendered-male foolishness. There also might be people who participated in these fistfights with an aim to physically hurt another person, but that’s not really what it’s about. The fights were eruptions, excesses. With chronological proximity of World War One, most of these men were teenage boys who saw millions of people die—they have a different relationship to violence. That’s a historical reality. It was a historical moment shared by women, although they certainly experienced the war in a different way. Maybe all of this is beside the point. Going back to the example of Giacometti’s Woman with Her Throat Cut, that is violence that is dramatic—

Yoshitake: At a gut level.

Lutker: It’s a horrifying piece for many different reasons. In my hysteria project, I was looking at these problematic depictions of “hysterical” women reenacting their symptoms for the sake of the archive and performing for their male doctors. I looked at the “medical” tools that were used to “treat” these patients, often in rather violent ways.

In this current body of work, I’m a female looking at these violent moments anew. In presenting these historical moments of the fistfights with all their complexities—the foolishness and failures of the Surrealists and their combatants—it humanizes them, makes them more real and of-the-world—instead of valorizing or reinforcing the generalized historical narrative. The work also highlights the fact that they were men who rejected women and homosexuals as part of their group. When they got angry, they acted out in immature ways, throwing fits, hitting, and spitting on each other.

Yoshitake: As part of your exhibition at the Hirshhorn, you selected historical works from the permanent collection to display near your own objects, which revealed certain formal or conceptual properties that you saw relating to the fistfights. For example, in Pablo Gargallo’s Kiki de Montparnasse (1928), Kiki’s mask is a fractured face split asymmetrically down the center. Both Man Ray’s Handle in Sleeve (The Hammer with No Master) (1967) and Square Dumbbells (1920–25/cast ca. 1964–66) evoke assault tools. The dumbbells contain the double entendre of speechless sound and nonfunctional objects due to their square form. There is a similar strategy here in the way you’re poking fun at the absurdity of these male-driven fistfights within these selected works by now canonical figures.

Lutker: I’m pointing to the absurdity, the childishness, the impetuosity. For the record, a lot of the Surrealists’ partners and love interests—women who were professionally, financially, and intellectually supporting them—were very present. Breton was married three times. Each of those women played an important role and greatly affected his work and frame of mind. A number of the artistic-political protests that resulted in fistfights coincided with his heartbreaks. Thinking symbolically, in the way in which I installed the permanent collection objects in the exhibition, Kiki de Montparnasse is there as a fractured, partial portrait, but simultaneously as all-knowing, the sun. She’s above them and looking over them.

Shana Lutker, Paul, Paul, Paul, and Paul, 2015, installation view, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, July 10–August 22, 2015 (artwork © Shana Lutker; photograph by Robert Wedermeyer)

Yoshitake: Man Ray’s Handle in Sleeve (The Hammer with No Master) questions or shifts the authorial subject.

Lutker: It’s also a hammer trapped in a bottle, so it can’t really function as a hammer anymore. It’s containing the violence. If you want to read it as a sexualized object, that’s there too.

Yoshitake: Lastly, how do you see the role of the writing in relation to the objects and performances?

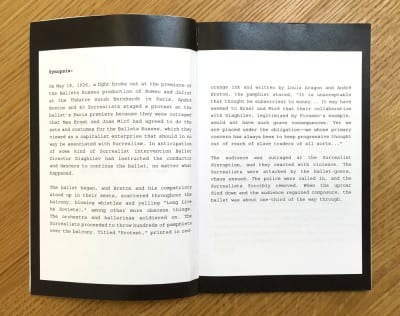

Lutker: In an exhibition, hierarchically it appears that the sculpture-objects are given priority. However, in the long view, the writing, the objects, and the performances all feel equal. Up to this point, I’ve presented the writing in tentative ways, as small pamphlets that are printed but not widely distributed. This is in part because I’m apprehensive about circulating the parts rather than the whole collection. I am uncertain of what will be revealed at the completion of the eight-part cycle. With the objects or performances, I learn from each one, and that shapes the next. It’s also true with the writing of each chapter.

Yoshitake: Your plan is to combine the eight chapters into a book?

Lutker: Yes, Le “NEW” Monocle: The History of the Fistfights of the Surrealists, chapters one to eight. But at this rate, it will be at least a few more years.

Shana Lutker is Los Angeles-based artist. In addition to Shana Lutker: Le “NEW” Monocle at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, recent exhibitions include a solo project at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, a commission for Performa 13 in New York, and solo exhibitions at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Barbara Seiler Galerie, Zürich; and Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm. Lutker’s work was also included in Passing Leap at Hauser & Wirth New York and the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Her work has exhibited in institutional solo and group presentations at US and international venues including the SculptureCenter, Long Island City, New York; The Center for Ongoing Research and Projects, Columbus, Ohio; SOMA, Mexico City; CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco; Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Russia; Disjecta Contemporary Art Center, Portland, Oregon; SALTS, Basel, Switzerland; Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, California; Public Fiction, Los Angeles; Gallery 400, Chicago; and John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Her work has been covered in Art in America, Artforum, New York Times, Artillery, Los Angeles Times, Hyperallergic, Blouin ArtInfo, and Frieze, among others. She is an editor of X-TRA, and received her MFA from UCLA.

Mika Yoshitake is associate curator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, where she has organized Shana Lutker: Le “NEW” Monocle (2015–16), Days of Endless Time (2014–15), Speculative Forms (2014–16), Sitebound: Photography from the Collection (2014), Gravity’s Edge (2014), and Dark Matters: Selections from the Collection (2012), and coordinated Ai Weiwei: According to What? (2012–13). She earned her PhD in art history from UCLA. Her dissertation on the late 1960s Japanese sculptural movement Mono-ha (School of Things) culminated in the exhibition and book Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha (Los Angeles: Blum & Poe, 2012), which received an AICA-USA award in 2013. Yoshitake was the fall 2014 guest curator of the ArtPace International Artist-in-Residence Program and guest consultant for outdoor sculptural commissions at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, Exposure, BT (Bijutsu Techo) International, and X-TRA, and she has contributed essays in How Does it Feel? Inquiries into Contemporary Sculpture (New York: Black Dog Publishing, 2016); Carl Andre: Sculpture as Place, 1958–2010 (New York: Dia Art Foundation, 2014); Tokyo, 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012); Lee Ufan: Marking Infinity (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2011); Target Practice: Painting Under Attack, 1949–78 (Seattle, WA: Seattle Art Museum, 2009); and © MURAKAMI (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007). Yoshitake is currently organizing a major North American tour of Yayoi Kusama’s infinity mirror rooms at the Hirshhorn, which will open in February 2017.

- Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria, trans. Alisa Hart (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 151; emphasis in original. ↩