I’ve been working since 2008 on a long, complex project centered on plants that grow in both the arctic (I always use the lowercase) and New York City, of which there are a surprising number. Along with identifying and pressing these plants, I’ve been reading eighteenth-century herbals and floras and more recent works on edible plants and botany generally, and have had a particular interest in mental travel and in writers who combine botany and literature. In composing my artist’s book of this project, The Arctic Plants of New York City, due out from Granary Books in April. I’ve thought of it as a walk among the arctic plants with various books as my companions along the way. I’d like to introduce you to a few of them.

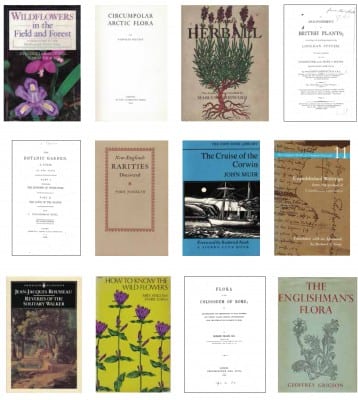

Steven Clemants and Carol Gracie, Wildflowers in the Field and Forest: A Field Guide to the Northeastern United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006)

This has been my favorite local field guide and my principal source for identifying plants. It is arranged by the color of the flower, which helps in identification, and it has clear photographs, descriptions, and range maps.

Nicholas Polunin, Circumpolar Arctic Flora (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1959)

This has been my bible. He writes a beautifully crisp, condensed botanical prose. I collated the index to this book, which contains every plant known to grow in the arctic, with the index to Clemants and Gracie, cited above, in order to come up with my list of the arctic plants of New York City.

Mrs. William Starr Dana, How to Know the Wild Flowers (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1893; rep. New York: Dover, 1963)

This was the first field guide, inspired by the naturalist John Burroughs, and it is still one of the best. Her prose is at once intimate and erudite, and she exudes the air of a relaxed, self-assured hostess as she leads the reader through the fields and forests, making introductions to each plant as it appears along the way, and sharing details of its history and use. She has had a definite influence on my prose style.

Erasmus Darwin, The Botanic Garden (Lichfield, 1789)

A terribly wonderful explication in verse of the famous Sexual System of the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus, by the grandfather of the more famous Darwin. I love Darwin’s ambition and confidence in this endeavor, and there are some beautiful and accurate ideas sprinkled through his rather undistinguished poetry. He spoke for me too when he opened the book with the words “The general design of the following sheets is to inlist Imagination under the banner of Science.”

Richard Deakin, Flora of the Colosseum of Rome (London: Groombridge and Sons, 1855)

This beautiful book was neatly summarized by the author when he wrote, “The object of the present little volume is to call the attention of the lover of the works of creation to those floral productions which flourish, in triumph, upon the ruins of a single building.” For each of the four hundred and twenty plants he found in the various microclimates of the ruin, Deakin gives a terse botanical description, a more fulsome and flowery description, a little bit about the plant, where it grows or what it looks like or something from its history or naming or its appearance in Ovid or Pliny, and he speaks of so many things that it is easy to forget that he is always inside the Colosseum.

John Gerard, The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (London, 1597; rep. London: Spring Books, 1964)

This is the classic old European herbal or description of the medicinal uses of plants, with woodcuts and descriptions pirated and adapted from earlier authors. It was immediately popular, despite being somewhat chaotic and inaccurate, and it went through various editions before being skillfully ordered and corrected in 1636 by the gardener Thomas Johnson.

Geoffrey Grigson, The Englishman’s Flora (London: Phoenix House, 1955)

A beautifully written and impeccably researched flora of the plants of England, with their various colorful local names, their uses as food and medicine, their history, and their appearance in folklore and literature. It is very close in spirit to my own project and makes me wish I had been the author. I plundered it ruthlessly.

John Josselyn, New-Englands Rarities Discovered (London, 1672; rep. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1972)

A very early, delicately observed description of the natural history of New England, including a sensitive account of the various native tribes. Even at this early date he wasn’t sure which plants were native and which had been introduced. Thoreau loved Josselyn, and they share a prose style that is at once closely observed and shot through with learning and imagination.

John Muir, The Cruise of the Corwin (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1917; rep. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1993)

An account of the naturalist’s first visit to Alaska as part of a scientific expedition aboard the steamer Corwin in 1881. Along with its scientific duties, the expedition was sent to search for signs of an expedition aboard the Jeanette, which had left two years before and not returned. As it later turned out, while Muir was in Alaska the Jeanette was north of Siberia, locked in ice, drifting, and eventually crushed, with the loss of most hands. Muir fared much better, returning at the end of a delightful summer with detailed accounts of the plants and landscape of Alaska, and vivid descriptions of the high- latitude optical illusions he witnessed there.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Writings from the Period of Unfashionable Observations, trans. Richard T. Gray (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999)

From his early notebooks, just bristling with his evolving thoughts on art, understanding, and the necessity of illusion, such as “If one were to conceive of the disappearance of all illusions, then consciousness, too, would evaporate down to the level of the plants.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Reveries of the Solitary Walker, trans. Peter France (1782; London: Penguin, 1979)

I love this sweet and sour little book. He gives a perfect example of actual objects provoking mental travel when he writes that his botanical walks, with all the thoughts and impressions he had along the way, are immediately brought back to him by the sight of the plants he pressed along those walks.

William Withering, An Arrangement of British Plants (London, 1796)

A very good example of an eighteenth-century English flora, with a well-written text and lively copperplate illustrations, and it is by Withering, an excellent name for someone who picks plants.

James Walsh was born in Brooklyn, NY, studied literature at Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Oxford University, and currently lives and works in Brooklyn. He has shown throughout the United States and Europe, and received a Fulbright Fellowship to Turkey. He is the author of numerous editioned and one-of-a-kind artists’ books as well as three books with small presses. His most recent book, The Arctic Plants of New York City, is forthcoming in April from Granary Books.