Karl Haendel, Knight #2, 2010, pencil on paper, 103 x 74 in. (261.6 x 187.9 cm) (artwork © Karl Haendel)

Episode Two, 2012

Since the rise of appropriation in American art of the 1980s, the strategy has become so commonplace as to evade continued examination as a unique vein of artistic practice. At the same time, recurrent intellectual property battles around appropriative gestures in contemporary art have threatened its viability, giving rise to College Art Association’s important report published in February 2015, the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. This three-part essay on the work of Karl Haendel, an LA-based artist best known for his arrangements of meticulously rendered drawings of found photographic imagery, connects three moments in his early career related to issues of artistic and cultural heritage and power. The first two episodes directly involve knights. Taking Haendel’s work as a point of departure and considering the digital turn, the essay as a whole examines how the operations, effects, and reception of appropriation have changed in recent decades and discovers what may be the strategy’s longest-lasting politics of signification. “Episode One” considered Haendel’s early project of reconstructing works by the minimalist sculptor Anne Truitt, including Knight’s Heritage (1963). This second text examines Haendel’s confrontation with another artist of an older generation, the early postmodernist Robert Longo.

Anne Truitt’s Knight’s Heritage, 1963, acrylic on wood, 60-3/8 x 60-3/8 x 12 in. (153.4 x 153.4 x 30.5 cm), installation view, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 2012 (artwork © Estate of Anne Truitt; photograph by Karl Haendel)

In late 2012, Karl Haendel entered a room in The National Gallery in Washington, DC, and before him stood Knight’s Heritage. The Knight’s Heritage. Here was the original sculpture Anne Truitt created in 1963, the very sculpture Haendel had labored so hard to reconstruct eleven years ago without ever seeing the original in person—until now. Haendel knew that sculpture so well, knew every inch of it (or so he thought). It was like running into an old, long-lost friend, maybe even a lover—or better yet, meeting a relative in person for the first time after knowing them only through pictures and stories. Haendel recalls the experience as deeply emotional, surreal, odd, strange, and wonderful. He felt a strong desire to put his arms around the sculpture and embrace it. In a sense he had already seen the work before, but of course not really. Knight’s Heritage was deeply familiar and at the same time not familiar at all. It was an uncanny experience.

Robert Longo, Untitled (Adam and Eve), 2012, installation view, Metro Pictures booth, Art Basel Miami Beach, 2012 (artwork © Robert Longo; photograph by Aram Moshayedi)

That same season would be marked by another set of uncanny encounters, experienced not by Haendel but by friends and colleagues who were attending Art Basel Miami Beach in December 2012. During the opening days of the fair, Haendel, who did not attend, received a series of e-mails and texts from people who claimed to have seen a drawing of his, but it was not credited to Karl Haendel. These messages of confusion were accompanied by evidentiary images that seemed to show that Haendel himself was now the subject of an act of copying, and the copier was none other than the artist Robert Longo. For on the wall of the Metro Pictures booth was a diptych composed of a life-size drawing in black charcoal of a knight in armor mounted next to a black charcoal drawing of the same size portraying a swimsuited female pinup wearing a hibiscus flower in her hair. The work was identified as Untitled (Adam and Eve), 2012, by Longo.

- Karl Haendel, Knight #3, 2010, pencil on paper, 103 x 74 in. (261.6 x 187.9 cm) (artwork © Karl Haendel)

- Karl Haendel, Knight #1, 2010, pencil on paper, 103 x 79 in. (261.6 x 200.6 cm) (artwork © Karl Haendel)

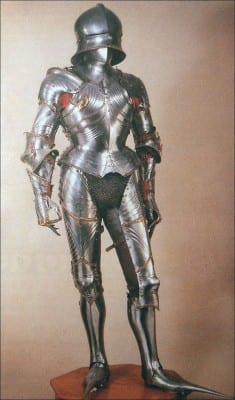

See, Haendel had already made a life-size knight drawing from the same source image in 2010. In fact, Haendel had made a whole series of knight drawings—eight of them between 2010 and 2011 titled Knight #1–#8. Rendered in graphite pencil on pages measuring 103 inches by a range of 74–83 inches, Haendel’s eight knights are faithful, scaled-up reproductions of four photographs of full-body armor suits characteristic of medieval and Renaissance Europe, drawn first after the original images and then each redrawn in a second version flipped on its vertical axis. Longo’s Adam was thus the doppelgänger not only of Haendel’s Knight #2 but also his Knight #6, who faces in the opposite direction but is still recognizable as the same knight. Between June 2010, when Haendel first started making the knights, and December 2012, when Longo’s “Sir Adam” emerged, Haendel’s knight drawings had been shown in Basel, Paris, Naples, New Orleans, and New York.1

Karl Haendel, Knight #2, 2010, pencil on paper, 103 x 74 in. (261.6 x 187.9 cm), incorporated into an installation of the artist’s work, Yvon Lambert Gallery, Paris, 2011(artwork © Karl Haendel)

I should be explicit that the point of this narrative is to lay neither blame nor claim regarding the knight image but rather to draw out the differences in two works of art that look nearly identical and were arrived at via similar technical means, but which signify differently when contextualized within each artist’s broader practice and art-historical position. There are consequential differences, differences that register in interesting ways the transformation of the meaning and operations of appropriative strategies from their emergence in the late 1970s to the present moment in which they have passed into the hands of younger generations of artists.

An example of 16th-century Maximillian armor. Source: https://rachelrussell.wordpress.com

/2012/04/30/medieval-monday-maximilian-armor/, as of April 1, 2016

For his part, Haendel came to the subject of knights in 2009 as part of his ongoing interest in exploring and creating expanded, more nuanced models of male subjectivity in contemporary art. Haendel relates that he began to consider knight’s armor as emblematic of the perils of emotional detachment in men, a means of protecting against vulnerability that also delimits experience and feeling.2 His first knight was drawn from the only high-resolution image of full-body armor that he could find online. It turns out that finding high-quality images of medieval armor is challenging, not only because authentic full-body metal armor is rare, but also because the armor’s reflective surfaces make it difficult to photograph. Haendel began searching for illustrated books on armor in libraries. He rented a full-body armor suit from a costume shop in North Hollywood specializing in historically accurate re-creations for film and television, and he wore the suit in a 16mm film made in 2010 that is reminiscent of the work of Jack Goldstein. Having learned that high-quality photographs of complete suits of medieval armor are nearly as rare as the books in which they’re published, he also borrowed one of the shopkeeper’s books and photographed the images in it. This is where he found the image he drew in Knight #2, unmistakable for the figure’s toe coverings, which double the length of each foot by extending outward in a single, bayonet-like talon, and, most especially, for the curious position of the left hand: the forefinger and thumb are joined to form a dangling “A-OK” sign. Only after Haendel had completed Knight #2 did the source image happen to make its way onto the Internet, in April 2012 as part of a post on a medieval enthusiast’s blog.3 Given the multitude of images that come up in Internet searches for knight’s armor, it is remarkable that Longo could have arrived at the same image for his Adam without knowledge of Haendel’s Knight #2. Could he or a studio assistant have happened upon the exact same book on armor as Haendel?

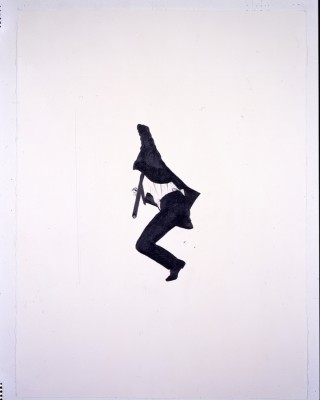

- Karl Haendel, Little Legless Longo #2, 2004, pencil on paper, 30 x 22 in. (76.2 x 55.8cm) (artwork © Karl Haendel)

- Karl Haendel, Little Legless Longo #4, 2004 pencil on paper, 30 x 22 in. (76.2 x 55.8 cm) (artwork © Karl Haendel)

It seems unlikely, not only because of all the aforementioned intricacies of this genre of images, but also because of another series of drawings reproduced from found images that Haendel had made in 2004, the Little Legless Longos. These were Haendel’s cheeky homage to Longo’s Men in the Cities series begun in 1979, which had made Longo famous as a first-generation postmodernist. The iconic series was inspired by a scene from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film The American Soldier (1970), in which the body of a man being struck by gunfire contorts into a bizarre position. With the intent to make a series of similar images drawn as if from film stills, Longo solicited friends to come to the roof of the Manhattan studio building he shared at the time with Cindy Sherman. There, he photographed the smartly dressed men and women as he threw tennis balls at them and pulled on their bodies with ropes so that he could catch their gyrating bodies in positions somewhere “in between dying and dancing.”4 Longo transformed the images into drawings in which the bodies are divorced from their original setting, cast afloat in a sea of negative space. If Haendel’s work bears similarities to Longo’s, it is to this body of work in particular, not only in terms of its form but also in its staging and intended meaning. As a recent catalogue essay describes Men in the Cities, “While many of Longo’s works portray figures, he does not consider the works to be figurative. Instead, he thinks of figures such as those in Men in the Cities as ‘abstract symbols,’ and ‘more like Japanese calligraphy or logos.’ Intended to be shown only in groups, the drawings are not meditations on the characteristics of individuals, but rather rough, forceful pictures of a time and a generation.”5

Robert Longo, Men in the Cities (Triptych), installation view of The Pictures Generation, 1974–1984, Great Hall, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2009 (artwork © Robert Longo; photograph by Eileen Travell)

Haendel’s quotational drawings after Longo’s Men in the Cities miniaturized the figures to the scale of Barbie dolls (he drew them on twenty-two- by thirty-inch paper, the smallest scale at which he works) and eliminated one of their legs each. The gesture effectually made some sense of Longo’s enigmatic images (now we know why they are falling), which had originally withdrawn their meaning in a characteristically obscure mode of postmodernist allegory. Haendel’s gesture also symbolically deflated the stature of a major artist of a previous generation. If his earlier monument to Anne Truitt (see “Episode One, 2000”) had been a sympathetic, honorific gesture of recognition whereby he recreated a sculpture of Truitt’s faithfully and in full—a gesture informed by his mentor Mary Kelly’s investment in the historical period of the 1960s and his search for art-historical mother figures to compensate for the loss of his own mother—here was Haendel’s juvenile moment of killing a father of 1980s appropriation art, the most recent art-historical canon that artists of his generation had to confront.

Robert Longo, Sickness of Reason, installation view, Metro Pictures, New York, 2004 (artwork © Robert Longo)

Interestingly, Longo has explained his own turn to the highly technical craft of rendering illusionistic imagery through drawing as its own protest against the asceticism of Conceptual art, the canon with which he himself had felt pressured to contend as a young artist. Here is a statement of his from 1986:

It is very important to understand that they [the Conceptualists] ripped apart the idea of art, they were in many ways descendants of Duchamp, they asked why do you have to hang things on white walls, why the art object, etc. It was strange to be the generation that came after these people, because they basically left us pictorially with nothing, maybe the love of the idea. . . .What happened is that drawing and painting, that sort of thing that was very traditional and that seemed outmoded and dead, came back. It seemed really radical to draw, to paint.6

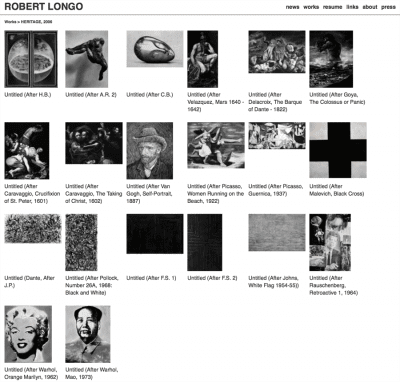

Robert Longo, Heritage series, 2006, screenshot of artist’s website, http://www.robertlongo.com/portfolios/1017, as of October 22, 2015

Launching his career roughly twenty years later, Haendel was indebted to Longo for making it acceptable to center an art practice on drawing at all. Although Haendel has claimed that Longo was less important to him as a model than more conceptually driven figures like Robert Barry, Alighiero Boetti, Mel Bochner, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, Robert Smithson, Allen Ruppersberg, and Lawrence Weiner (and moreover Haendel maintains that many conceptualists were deeply concerned with craft), among these artists it is Longo who is most famously recognized as a draughtsman.7 Indeed the remarkable similarly between Haendel and Longo’s working processes could be seen to trump any privileged conceptual lineage in which Haendel would want to place his work: both artists make black-and-white drawings from photographic images, often appropriated (although Longo does this perhaps more so than Haendel, who uses a mix of appropriated and custom-made images). The images are enlarged from their original dimensions by means of a projector or grid system and drawn by hand. What Haendel’s Little Legless Longos importantly registered, however, is that the Longo of 2003/2004 was very different from the Longo of 1986. At the time Haendel began making the legless drawings, Longo’s most recent show at Metro Pictures, The Sickness of Reason, had featured enormous illustrations of nuclear explosions. The title of the exhibition implied a critique of the ends of scientific rationality, but nevertheless the drawings monumentalized and fixed as elegant each individual scene of destruction, from Nagasaki to Bikini Atoll, as an iconic image for aesthetic delectation. The suggestion of a postmodernist critique of representation or authorship had all but evaporated. Longo was still redrawing images in series, but his choice of subject matter along with the drawings’ craftsmanship and scale now seemed to celebrate the awesome beauty of the sublime image, with each presented as a singular masterpiece. At age fifty, Longo seemed already to have entered what Edward Said has theorized as an artist’s “late style”—grandiose, irascible, and intransigent.8 By 2004 Longo had drawn nuclear explosions, tidal waves, rose blossoms, and pistols; soon would come sharks, planets, fighter pilot masks, cleavage, and sleeping babies. If Longo and Haendel’s drawings looked superficially alike, the Little Legless Longos were Haendel’s effort to distance himself from the twenty-first-century Longo. His miniaturized, legless, falling Longos critiqued the excesses of that artist’s contemporary work and were also a reminder—to Haendel and, perhaps optimistically, to Longo as well—of why Longo had become celebrated as an artist in the first place.

Graphite, installation view showing the work of Karl Haendel (left) and Robert Longo (right) on opposite sides of the same wall, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, Indiana, December 7, 2012–June 2, 2013 (artwork © Karl Haendel; artwork © Robert Longo; photograph provided by Indianapolis Museum of Art)

Remarkably, among Longo’s next series was Heritage, begun in 2006, comprised of drawn copies of canonical masterworks by Hieronymus Bosch, Auguste Rodin, Constantin Brancusi, Diego Velázquez, Eugène Delacroix, Francisco Goya, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Kazimir Malevich, Jackson Pollock, Frank Stella, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol, among other artists. What’s more, Longo’s copies were rendered in miniature, with none appearing on paper any larger than nine by eleven inches. Untitled (After Picasso, Guernica, 1937), for example, appears on the scale of three and one-half by seven and three-fourths inches. The Heritage project is described on the artist’s website thus:

Well known for his series of large-scale drawings of crashing waves, atomic explosions, planets, sharks and views of Freud’s consulting room, Longo has in recent years begun making intimately-scaled drawings of iconic artworks that have inspired or informed his own works. Typically no more than four by six inches, the works are drawn in graphite with astounding detail and are a radical shift in scale for the artist. Longo views these works as an art historical family tree—an homage to his ancestors and heroes. To date he has drawn works by Caravaggio, Brancusi, Rodin, Warhol, Bosch, Pollock, Hopper and Johns, among others. Each is an artwork in which Longo has found great inspiration.”9

Here was Longo placing himself, in a rather uncomplicated and unironic fashion, in line with a longue durée of modern masters by absorbing their work very literally into his practice. It was an exercise remarkably similar to Haendel’s efforts to reconstruct the work of Truitt and to ape the work of Longo—except, crucially, for its lack of conceptual complexity and self-criticality. The 2013 exhibition Graphite at the Indianapolis Museum of Art offered a moment to consider Longo and Haendel’s practices side by side, for on the opposite side of one wall of Haendel’s installation of drawings was a selection from Longo’s Heritage series, described in the exhibition catalogue as Longo’s redrawn collection of works by artists “who similarly sought a sublime universality.”10

Robert Longo, Gang of Cosmos, installation view, Metro Pictures, New York, 2014 (artwork © Robert Longo)

It is unclear whether Longo’s Heritage works came about with any knowledge of Haendel’s just-prior incorporation and miniaturization of the older artist’s work, although it is rumored that Longo knew of Haendel’s amputated homages. If so, Longo’s Heritage works could be read as a rejoinder to Haendel’s Little Legless Longos that posits “appropriate” ways of relating one’s work to art history and attempts to reclaim and realign Longo’s legacy in ways that lead back to great artists of the past rather than forward to an (unruly) younger generation. In other words, Longo’s gesture deflects the critical line Haendel had drawn between his and the older artist’s practice. If such awareness on Longo’s part cannot be affirmed, what is clear is that the Heritage drawings forecast the artist’s much-acclaimed 2014 series Gang of Cosmos, in which his typical grandiose scale returns. This body of work includes twelve exquisitely rendered graphite drawings of famous Abstract Expressionist canvases, some of which are enlarged even further beyond their already heroic true size. Executed with close access to the paintings, Longo’s stunning renditions are so detailed that they depict the texture of the canvases and the differing viscosities of paint.11

Karl Haendel, installation of Knight drawings at the Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans as part of Prospect.2, 2011–12. Left to right: Knight #6, Knight #4, and Knight #5 (all 2011) (artwork © Karl Haendel)

By appropriating in his own signature style a most heroic mode of American modernism, premised as it had been on the monumentalization of the artist’s aesthetic signature or autographic mark, Gang of Cosmos is a consummate example of what Nate Harrison has identified as “the reassertion of authorship in postmodernity.”12 Registering the changed significance of Pictures-Generation work in the decades following its initial critical reception, Harrison argues that the appropriation artist’s unique approach to recontextualizing readymade cultural materials has effectively come to constitute an autographic style, and he compellingly relates this shift to transformations in intellectual property law. On the work of Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince, he writes, “Rather than undermining any romantic notion of authorial originality in a culture of the copy, the works reasserted the very productive core of the romantic authorial mode––one premised on private ownership through labor.”13 If we consider in addition the promotional rhetoric surrounding recent retrospective exhibitions of Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman—Prince, for one, having been ascribed a “deeply personal vision” that betrays “a uniquely individual logic”—this reassertion of authorship is plain to see.14 If these artists were celebrated in an earlier time for revealing expressionist modes of artmaking to be utilizing, as Hal Foster writes, “a language so obvious we may forget its conventionality and must inquire again how it encodes the natural and simulates the immediate,” over thirty years later, in a time when those critical revelations have themselves become canonical, we must now parse how individual appropriation practices differently recode the cultural and its always-already mediated nature.15

Karl Haendel, Knight #8, 2011, pencil on paper, 103 x 79 in. (261.6 x 200.6 cm) (artwork © Karl Haendel)

Returning to the coincidence of Haendel and Longo’s drawings of the same knight, isn’t it appropriate that what seems to have been Haendel’s first moment of recognition by an artist of the Pictures Generation occurred through an act of appropriation? Was it calculated on Longo’s part, or truly coincidental? If Longo indeed knew of Haendel’s knight drawing, how are we to understand the meaning of his act? Because of Longo’s stature, does his knight “trump” Haendel’s knight? Or is Longo’s knight a knowing wink at Haendel, as if to say, in either a friendly or passive-aggressive way, I caught you? I pose these questions and leave them definitively unanswered for the reason that Longo has repeatedly declined to engage in dialogue with Haendel or about Haendel’s work. When both artists were included in the 2013 group show Graphite, curator Sarah Urist Green invited all participating artists to interview one another for the catalogue. Haendel’s request to interview Longo was declined by the artist’s studio, and there has been no contact between them since. In August 2015, Longo’s studio also declined my request for an interview on the topic of the relation between the two men’s work (this essay is in part a project to get these moves, countermoves, and avoidances on the record). So we are left to speculate upon the reasons for Longo’s refusal. One may be that, understandably, Longo rejects Haendel’s reading of his work, which seizes it as a historical type indexed to a decidedly past moment in art history. Furthermore, Longo’s interests seem to have moved on from a critical engagement with visual semiotics, and the artist therefore may not want to foreground appropriation as the dominant framework for understanding his practice. We may never know.

In any case, despite the obvious connections between Longo and Haendel’s work there are crucial differences between their twin knights, which deserve close reading and disentangling. If both Longo and Haendel’s knights offer a wry take on stereotypical ideals of male subjectivity (and in the case of Longo’s Untitled (Adam and Eve), of female subjectivity too), Longo’s knight remains a heroic figure nonetheless. A replication of the found image in toto, his knight stands with confidence on a solid platform and is framed by dark shadows. Haendel’s knight, meanwhile, stands on nothing; it is set adrift, stranded in the middle of a white page, devoid of all worldly context (as Longo’s Men in the Cities had been). Notes from Haendel’s therapy sessions scrawled next to other knights in the series further cast them as insecure, pathetic, and emotionally impotent. Next to Knight #8 Haendel has listed feelings that lead to a sense of security: “not judged, accepted, interested in, paid attention to, cared for, loved, feel special, BELONG”—as if the knight before us has somehow exposed himself. But all there is to see is a mute metal object in a human shape.

Karl Haendel, detail of Knight #8, 2011, pencil on paper, 103 x 79 in. (261.6 x 200.6 cm) (artwork © Karl Haendel)

Where Haendel’s unmoored knights ultimately find context is in the groupings of drawings the artist assembles when his work is displayed in exhibition. Very rarely does a Haendel drawing appear alone, for his working process is opposed at every turn to the singular image. Haendel finds or creates photographic images, converts them to 35mm slides, and catalogues them in an idiosyncratic system of categories. The typology of Haendel’s image archive runs roughly from Abstracts to X-Rays, including categories such as Babies Crying, Hitler, Local Churches, and Tupperware in between. Longo too constitutes a category, and each of these categories is populated by multiple images. The drawings Haendel makes from these images are typically done in multiple as with the several knights, and the finished drawings become part of a second inventory that Haendel assembles into groups for specific exhibition contexts. Individual drawings may be pulled into different groups on different occasions, each time contributing to a particular, momentary visual syntax that is liable to be radically transformed the next time it appears. (That is, until a particular grouping enters a collection as a group—but then Haendel can always redraw an image from his slide bank, effectively appropriating himself.) To underscore the radical provisionality of his practice of arranging the finished drawings, Haendel has exhibited his slide collection as ever-changing room-sized installations, in which slide projectors mounted at varying heights and distances from the walls project edited selections from his archive.16 With each slide carousel organized by the artist according to specific thematic connections, the chorus of projectors creates indeterminate juxtapositions as the machines churn through their carefully edited contents. In Haendel’s porous and cross-referencing taxonomies, an image can be readily appropriated from one category to the next. If an image of Bob Dylan signifies America in one installation, it may go on to represent Masculinity/Heroes/Anti-Heroes in the next.

Karl Haendel, Shrink, 2005, five drawings of pencil on paper, dimensions vary (artwork © Karl Haendel)

There is an analogy to be made between Haendel’s syntactical practice and the workings of language, which other writers have readily identified.17 Indeed, the individual drawings are for the artist integers, words, syllables, or even discrete phonemes that come in and out of relation with one another, suggesting different meanings depending on how they are grouped. From commonly recognizable cultural material, Haendel builds allusive visual syntaxes. In this way, his entire oeuvre can be seen as an ever-shifting, contemporary mnemosyne atlas, one that recognizes visual culture as a language of aesthetic types and codes used and shared between us but owned by no one. “All ‘types’ of images have already been produced and there is nothing new there,” Haendel has said.18 “I’m not the author of the image. The image belongs to culture at large, and I am only involved in the chain of passing it on.”19 Haendel envisions his inventory of images as part of an endless chain of images connected by the logic of and . . . and . . . and . . ., a logic emblematized by the interbraided loops that make up the logo of his book publishing imprint, Double Ampersand Press (&&).

Installation view of Karl Haendel’s drawings in Uncertain States of America: American Art in the 3rd Millennium, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, 2006 (artwork © Karl Haendel)

In Jonathan Lethem’s 2007 essay, “The Ecstasy of Influence,” a remarkable meditation on cultural appropriation whose text was largely (and openly) copied from other authors, art and language are similarly characterized as part of a “vast commons,”

one that is salted through with zones of utter commerce yet remains gloriously immune to any overall commodification. The closest resemblance is to the commons of a language: altered by every contributor, expanded by even the most passive user. That a language is a commons doesn’t mean that the community owns it; rather it belongs between people, possessed by no one, not even by society as a whole.20

Our acceptance of the unruly passage between people of words and images in popular culture is indeed what makes it popular, as distinguished from the sphere of fine art and its highly individual creations. Walter Benjamin once characterized this distinction in compelling fashion: “Folk art and kitsch ought for once to be regarded as a single great movement that passes certain themes from hand to hand, like batons, behind the back of what is known as great art.”21 For better or worse, in the wake of the general acceptance of appropriative gestures the distinction between popular and fine seems increasingly arbitrary and artificial. In the visual culture that Haendel is typically after, certain images achieve the status of a common “type” from wear if not overuse, from passing through the bricoleur practices of countless subjects, each with the capacity to alter the general valence of a ubiquitous image only slightly. The images that circulate in the general culture may seem original to their users, but mostly, Haendel’s practice reminds us, they are copies. Next to such a practice, the intellectual property quarrels that continue to plague artists like Jeff Koons and Richard Prince, who have been using appropriation in their work for over thirty-five years now, can seem like a conservative last-gasp reaction-formation to the efflorescence of image thievery that has come about in the wake of the radical dissemination and decontextualization of images brought by the workings of the Internet and social media. Once an image enters the flow of popular culture nowadays, it is nearly impossible to extract it.22

Karl Haendel, High Performance Stiffened Structures, installation view, Locust Projects, Miami, 2013 (artwork © Karl Haendel)

If not Longo, there is at least one artist associated with the moment of the 1980s with whom Haendel feels consciously affiliated. The young artist first began to think deeply about the interrelations of image- and object-types while working as a studio assistant for Haim Steinbach over the course of three years, beginning during his time in the Whitney Independent Study Program in 1998–99 and continuing until his move to Los Angeles. Steinbach’s readymade consumer items, set on shelves in careful arrangements, invited thinking about how we read objects individually and in relation to one another according to material, historical, and metaphorical registers. What’s more, Steinbach loved shopping and loved the objects he chose to work with. He was an artist from whom Haendel learned very directly that the act of collecting and reframing readymade cultural products could be a gesture of affection, engagement, fascination, affiliation, and identification.23 In Haendel’s installations there are typically no shelves, but clearly there is a similar dynamic of careful placement and display at work. The spaces between one drawing and the next are as crucial as the individual works themselves.

Karl Haendel, Grits Ain’t Groceries (All around the World), installation view Anna Helwing Gallery, Los Angeles, 2005 (artwork © Karl Haendel; photograph by Josh White)

In 2005, Haendel showed two of his Little Legless Longos at Anna Helwing Gallery in Los Angeles as part of a grouping around the theme of impotence that also included his drawn reproductions of the following: exclamation points tilting as if falling, an allusion to the feeling of ineffectuality surrounding street protests against the Iraq War; the Trump Building at 40 Wall Street, for a brief time—less than a month—the tallest building in the world; and a temporary, site-specific gallery intervention by Kishio Suga, Limitless Situation (Window), 1970, in which the artist propped opened adjacent windows at the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto with blocks of wood. Precarious erections all. It would be entirely appropriate to call Haendel’s loose associations of images, which suggest unexpected or illogical connections between disparate things, an example of knight’s-move thinking.

To read Nate Harrison’s response to this essay, click here.

Natilee Harren is assistant professor of contemporary art history and critical studies at the University of Houston School of Art. Her research engages experimental, interdisciplinary practices after 1960, with particular emphasis on intermedia art and theories of translation between artistic mediums and disciplines; the role of notations, scores, and diagrams in conceptual and performative art practices; institutional critique; social practice; and theories of appropriation. Her current book project, “Objects without Object: Fluxus and the Notational Neo-Avant-Garde,” examines the work of the international, neo-avant-garde Fluxus collective amid transformations of the art object wrought by score-based practices of the 1960s and the epochal shift from modernism to postmodernism. Harren is also coeditor of a critical anthology, forthcoming from the Getty Research Institute, which surveys and theorizes a range of twentieth-century experimental notations from the fields of performance art, dance, literature, and music within a media-rich digital platform. Her essays and criticism have appeared or are forthcoming in Art Journal and Getty Research Journal, among other publications, and she has been a regular contributor to Artforum since 2009.

- Yvon Lambert Gallery’s booth, Art Basel, Switzerland, 2010; solo exhibition at Yvon Lambert Gallery, Paris, 2011; solo exhibition at Galleria Raucci/Santamaria, Naples, Italy, 2011; Prospect.2 New Orleans, 2011; Gallery artists group show, Harris Lieberman Gallery, New York, 2012. ↩

- Karl Haendel, telephone interview with author, September 2, 2014. ↩

- Rachel Russell, “Medieval Monday: Maximilian Armor,” April 30, 2012, at https://rachelrussell.wordpress.com/2012/04/30/medieval-monday-maximilian-armor/, as of July 21, 2015. ↩

- Ralph Goertz, “Robert Longo at Galerie Hans Mayer, Düsseldorf,” YouTube video, 3 min., 22 sec., posted by the Institut für Kunstdokumentation und Szenografie, April 5, 2009, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UgXr9TfuXow, as of July 20, 2015. ↩

- Sarah Urist Green, ed., Graphite, exh. cat. (Indianapolis, Indiana: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2013), 148. This was a group exhibition that included both Longo and Haendel, whose works were shown in adjacent rooms, including on opposite faces of the same wall. ↩

- Richard Price, interview with Robert Longo in Robert Longo: Men in the Cities 1979–1982 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 96–97; quoted in Neal Benezra, “Overstated Means/Understated Meaning: Social Content in Art of the 1980s,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art 2, no. 1 (Winter 1988): 30. ↩

- Karl Haendel, telephone interview with author, September 2, 2014. ↩

- Edward W. Said, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Vintage Books, 2006). ↩

- Robert Longo, Heritage portfolio, 2006, at http://www.robertlongo.com/portfolios/1017/works/32377, as of July 20, 2015. ↩

- Green, 155. ↩

- Out of Sync and Marc-Christoph Wagner, “Robert Longo: I Am an Image Thief,” YouTube video, 8 min., 59 sec., posted by Louisiana Channel, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, December 9, 2014, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dEf-JjqFyNg, as of July 22, 2015. ↩

- Nate Harrison, “The Pictures Generation, the Copyright Act of 1976, and the Reassertion of Authorship in Postmodernity,” Art&Education Papers, at http://www.artandeducation.net/paper/the-pictures-generation-the-copyright-act-of-1976-and-the-reassertion-of-authorship-in-postmodernity/, as of July 22, 2015. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Seth Waugh, “Sponsor’s Statement,” in Nancy Spector and Richard Prince, Richard Prince (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2007), quoted in Harrison, “The Pictures Generation.” ↩

- Hal Foster, “The Expressive Fallacy,” Recodings: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics (New York: The New Press, 1999), 60. ↩

- One such exhibition was Oral Sadism and the Vegetarian Personality, Human Resources, Los Angeles, 2012. ↩

- See Gloria Sutton, “Karl Haendel: The things that I am about to tell you are the things that I have come to regard as true,” in ed. Sutton and Gabriel Ritter, MOCA Focus: Karl Haendel, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2006), 11–54; and Michelle Grabner, “Karl Haendel,” in Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing, ed. Matt Price (New York: Phaidon, 2013), 100. ↩

- Karl Haendel, “Complicated Sneakers,” in Juan Roselione-Valadez, ed., Beg Borrow Steal: Rubell Family Collection (Miami: Rubell Family Collection, 2009), 86. ↩

- Karl Haendel and Aram Moshayedi, unpublished conversation, May 7, 2013. ↩

- Jonathan Lethem, “The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism,” Harper’s Magazine (February 2007): 66. Lethem here copies Michael Newton’s review of Daniel Heller-Roazen’s book, Echolalias: On the Forgetting of Language (New York: Zone Books, 2005), published in the London Review of Books in May 2005, emphasis in original. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “Some Remarks on Folk Art,” (1929) in ed. Howard Eiland, Michael W. Jennings, and Gary Smith, Selected Writings, vol. 2 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999), 278. ↩

- David Joselit has compellingly theorized this new ecology of images in After Art (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013). ↩

- Haendel, “Complicated Sneakers,” 85. ↩