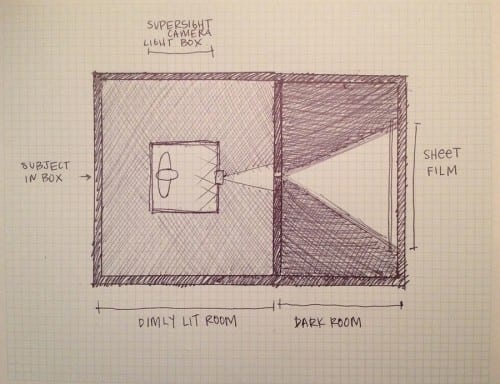

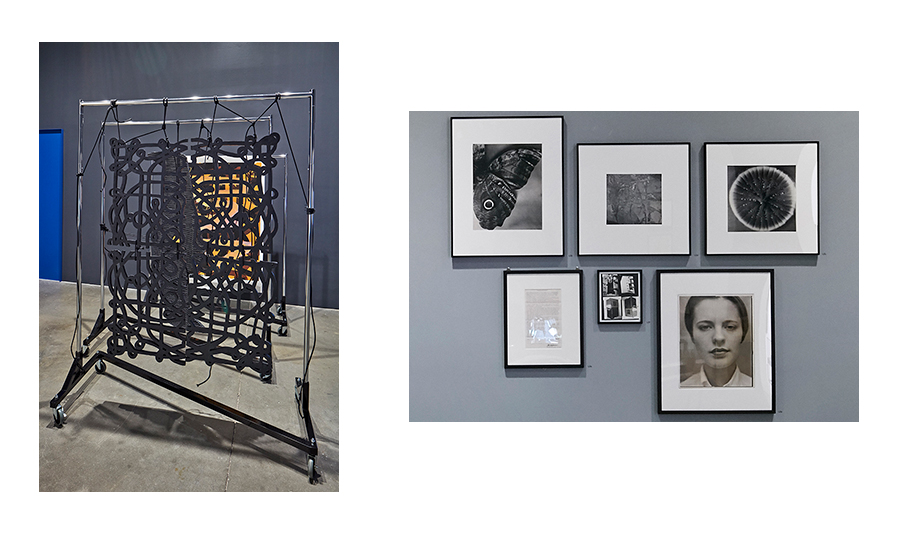

Berenice Abbot, Super Sight camera set up, n.d. (photographs © Berenice Abbott/Commerce Graphics Ltd, Inc., Berenice Abbott Archive, MIT Museum, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Gift of Ron and Carol Kurtz)

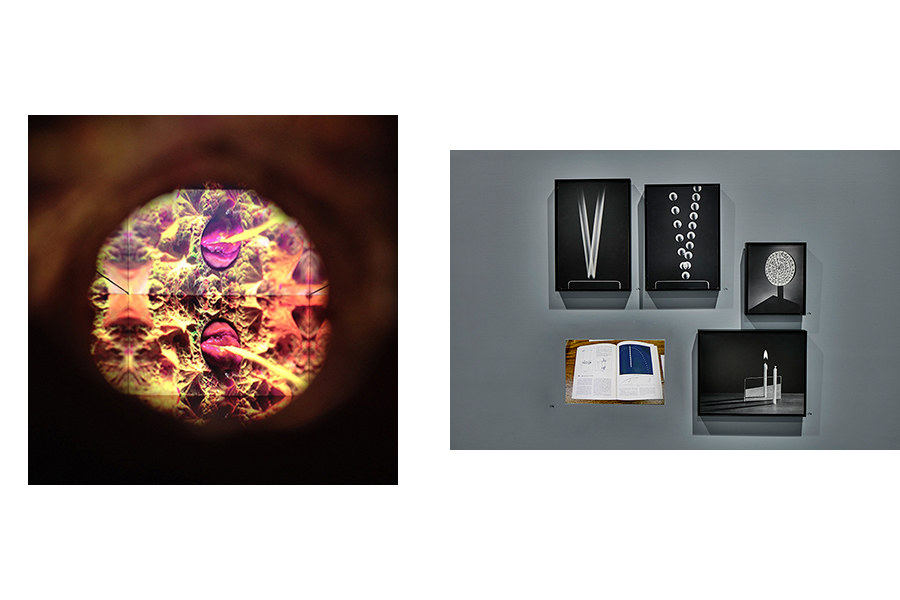

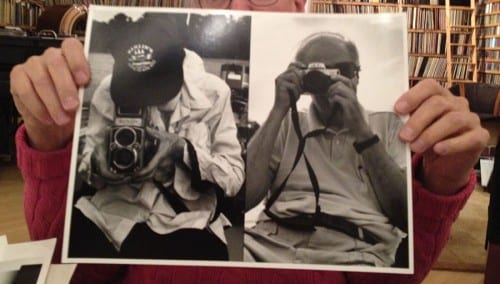

In the early 1940s, Berenice Abbott (1898–1991) developed a form of macrophotography she called Super Sight. Over seventy of the negatives and fifty of the photographs that she made using this method exist today. Abbott’s process was never documented in full, and the exact mechanics of Super Sight remain a mystery. During my research on her work, only one person—Hank O’Neal, a friend of Abbott’s and also a photographer—was confident enough in his understanding of the technique to explain it to me when we met. Abbott had described the setup to him thirty or forty years prior to our meeting.

Hank O’Neal holds a photograph depicting himself and Berenice Abbott taking photographs of one another, 2015 (photograph © Hank O’Neal; photograph © Anna Craycroft)

The Super Sight method began with Abbott dividing her small Manhattan studio on 50 Commerce Street into two rooms. One half was dimly lit. The other half was pitch black. A camera-like device sat in the middle of the dimly lit room, and the subject to be documented was placed inside. Bright light flooded this small space and refracted in the camera’s lens. A cone of light was cast outward across the dim room. By inverting the balance of light between the interior and exterior space, the retrofit box camera transformed into a projector. The projected image did not stop at the wall of the room: Abbott had drilled a small hole in the wall so the projection continued through it to the adjacent, pitch-black room. Traversing each discrete space of the Super Sight setup, the image grew progressively larger and more finely detailed. It was ultimately captured on a large sheet of photosensitive film hanging on the far wall of the pitch-black room. After being magnified twice, inverted, and reverted, the resulting negative was high definition and larger than life.

The convoluted rigging of Abbott’s architectural contraption employed DIY mechanics that are almost preposterously logical. But no matter how homespun, the Super Sight process (alternately referred to as the Abbott Process or Projection Photography) was an invention. It was innovative, creative, inspired, and original. By delicately tweaking what was immediately available to her, Abbott’s device performed a function previously unrealized in photographic technology. The macrophotography of Super Sight enlarged the image directly onto the photosensitive film, creating a sixteen-by-twenty-inch negative with sharp contrast and fine detail. With it, Abbott could document any solid object that fit within the interior space of her projection camera. Her Super Sight photographs were hyperbolically hyperreal. Everyday subjects were elevated from mundane observations to scientific investigations. Abbott made oversized images of faces, corn husks, minerals, tree bark, a variety of insect and animal specimens, and the palm of a hand. Exposed squarely to fill the frame, these quotidian subjects reveal the remarkable. As in all of her photography, Abbott’s poetics are plain and frank. She tells you what you already know but didn’t pay attention to. Or what you didn’t realize you had been staring at all this time.

When I look at Abbott’s photographs, their candor feels so generous that it is almost deferential. Their voice seems to belong as much to Abbott as to her subject or her viewer. This emphasis on legibility serves the civic and pedagogical platforms by which Abbott created her work. What I marvel at most is that she achieves this accessibility without compromising the poetry of each piece.

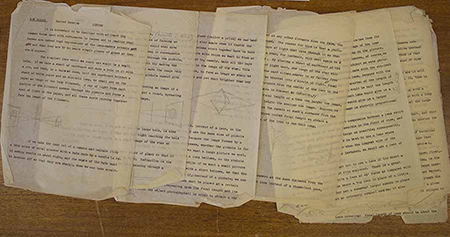

Since first becoming aware of Abbott a few years ago, I have tried to understand how she created this effect. I wanted to learn the working process behind each photograph and was interested initially in the mechanics of their making. I quickly grew more curious about the work that surrounded and supported what she did with her camera and in her darkroom. I made multiple visits to her archives at the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Ryerson Image Center in Toronto, New York Public Library, and Museum of the City of New York to learn as much as I could. I developed evolving conversations with various historians, librarians, curators, and friends of Abbott’s. The more I understood about her practice, the more personal my research became.

In over twenty years of studying or teaching in a succession of art schools, I must have come across Abbott’s photographs before, but I didn’t see them until some were included in Trisha Donnelly’s Artist’s Choice exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 2013. It seems appropriate that it was another artist who laid bare the paradoxical power of Abbott’s images. Donnelly’s selection and arrangement of works from MoMA’s collection was—much like her own artwork—at first mesmeric and confounding, but then surprisingly self-evident. Abbott’s prints hung alongside art and artifacts spanning approximately one-hundred-and-forty years. Each painting, sculpture, drawing, piece of furniture, and diagram had its own mysterious logic. Seeing Abbott’s work in this context revealed the fastidious attention that underscores the seemingly simple constructions. The boldness of her images concealed a history of making that required further decoding.

Key to my introduction to Abbott was what brought me to Donnelly’s exhibit in the first place, further setting the tone of how I encountered Abbott’s work. I was at MoMA to attend Poetry Parade, a roving event created by the artists A. K. Burns and Katherine Hubbard. For each Poetry Parade, Burns and Hubbard invite a small group of artists, writers, and curators to join them in leading an evening of readings at an art museum. Walking from room to room with an audience of museumgoers, the group periodically stops so a reader can address an artwork. Most choose to read writings by others. Viewing the work becomes a process of applying outside voices to personal experience. In a commingling of consensus and interpretation, the intimate relationship that typically takes place between an audience and an artwork is multiplied and externalized. The collective viewing and interchange of readings in the Poetry Parade befits the generosity that I came to recognize in Abbott’s work.

I noticed her ripple-tank photograms across one of the galleries that the Parade visited. The work seemed familiar yet difficult to place. I broke away from the migrating group with fellow audience member, the artist Jonah Groeneboer, to look more closely at the prints. Jonah explained to me the scientific principles that were being illustrated by the photographs. As he spoke, the didactical function of the work grew more evident. The works had originally been commissioned by the Physical Science Study Committee (PSSC) to illustrate different principles of wave formations in high school textbooks. Formed in 1957, the PSSC had consisted of a group of MIT professors and high school teachers devoted to reform the teaching of physics. Even as Abbott’s photographs satisfied their pedagogical purpose, they still evaded explanation. They were empirical and illusory, explaining a scientific fact through a fabricated form. What did it mean if an artwork was both enigmatic and didactic? How was it that Jonah and I could unpack the work together and grow more curious the more we understood? I decided to find out as much as I could about Abbott’s working methods.

Abbott’s work crossed boundaries, broke rules, and created new forms. Through her passion for photography she acted as a historian, archivist, curator, inventor, educator, author, and activist. Each accomplishment was born of necessity in her service and dedication to photography. When a photographer she greatly admired—Eugène Atget— died, she knew that if she did not collect, preserve, reprint, and promote his work, his legacy and an entire language of photography might be lost. When she wanted to ease the cumbersome load of photo equipment she schlepped through the streets of New York, she invented carrying tools and candid cameras. When she struggled for money during the Depression, she created a teaching job for herself by initiating a photography course at the New School. When she needed to build a lexicon for her work, she lectured and published papers that established an art-historical lineage to which she felt allied. When she needed an assistant to help realize her work in the studio but couldn’t afford one, she made an appeal to the New York State Department of Education to subsidize apprenticeships for commercial photographers.

If Abbott were an artist working today, these various efforts could be considered part of her art practice. She might be called a multimedia or a transdisciplinary artist. But she was a polymath only so she could grow as a photographer. That the singularity of her focus resulted in such a diversity of engagements reveals how the very discipline of being an artist can be inherently expansive. By extension, an argument could be made that our contemporary focus on cross-disciplinary work overlooks its own historic precedents and naively condescends to its current practitioners. I myself have stumbled over these and other ill-fitting monikers that are designed to classify and explain my refusal to follow a familiar and consistent method or medium. I do not consider the range I work in to be “post-studio” or uniquely “research-based” or at all “dematerialized”. Instead the variety in my work is simply the result of exploring the parameters of being an artist: a practice defined by its expansiveness and mutability. Abbott’s legacy has inspired new ways for me to approach this understanding.

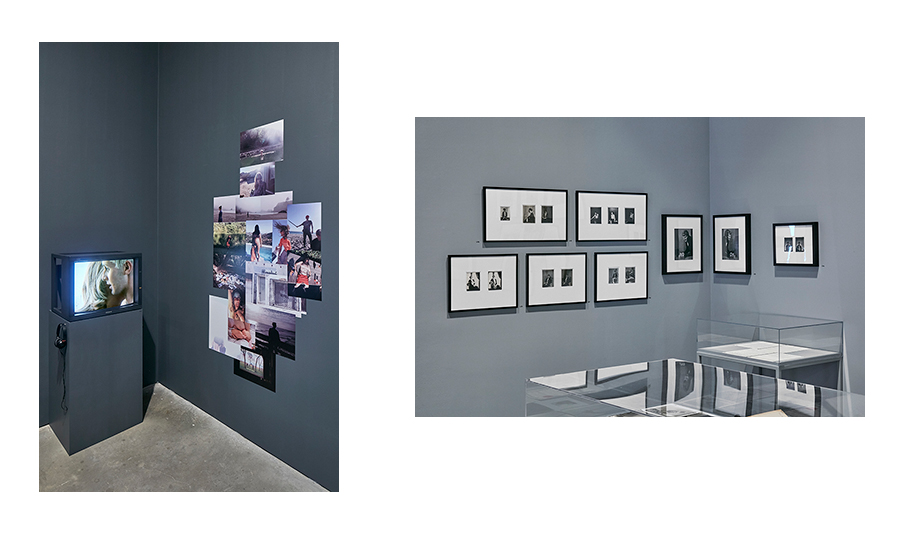

Early in my research, I discovered that I was associating the various aspects of Abbott’s practice to those of artists working today. I began to develop a project highlighting these connections. My plan was to pair Abbott’s works with contemporary pieces that derived from photography, but were executed in a variety of media. This project provided me with a form to reflect on how the range of Abbott’s practice expands the parameters of an artistic discipline beyond the limitations of being either singular or plural. In the fall of 2015, Dan Byers, a senior curator at Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, commissioned me to realize this project for his exhibition The Artist’s Museum (November 15, 2016–March 26, 2017). I titled my work The Earth Is a Magnet, after a comment of Abbott’s in an interview made for the 1992 documentary Berenice Abbott: A View of the Twentieth Century. In the clip Abbott expresses her delight in this scientific phenomenon, revealing the genuine curiosity that is so central to her work. The Earth Is a Magnet plays with the principle of attraction and interconnectivity in a mirroring installation of artworks across a two-room divide.

One room, dedicated to Abbott, is divided into nine thematic categories that classify over eighty pieces of her photography and ephemera into distinct aspects of her practice: inventions, portraits, Super Sight, and more. The other room displays recent works in sculpture, animation, photography and drawings by nine contemporary artists: Jill Magid, Matt Keegan, Erika Vogt, A. L. Steiner, Katherine Hubbard, Lucy Raven, Fia Backström, Mika Rottenberg, and MPA. Each of the works I selected from these artists bears a likeness to one of the nine thematic categories that I designated for the Abbott room. None of the artists made their works in response or reference to Abbott. As these nine artists are people with whom I work closely, I thought about each of their practices as I researched Abbott—the connections drawn between their works and Abbott’s are my own associations. I underscored the likenesses by displaying the associated works in the same locations on either side of a dividing wall.

Jill Magid’s sculpture investigates the legal parameters of the architect Luis Barragan’s legacy. A parallel is drawn to Abbott’s work on the legacy of Atget, represented in the exhibition by an article, a book, and portraits of Atget. Matt Keegan’s steel sculpture is powder coated in the “federal blue” color of New York City’s Hells Gate Bridge; Abbott’s black-and-white photographs capture the steel cables and girders of the Manhattan, Queensboro, and Brooklyn bridges. Three hanging sculptures by Erika Vogt magnify the various textures of a repeating form, as six of Abbott’s Super Sight photographs show the contrasting details of her macrophotography. A. L. Steiner’s photocollage assembles intimate moments with friends and lovers, while Abbott’s portraits are solitary stagings taken in her studio. Water acts as camera and lens for both Katherine Hubbard’s ice photograms and Abbott’s water-ripple photograms. Lucy Raven’s stop-frame animation deconstructs the mechanisms of the 3-D film industry. Abbott’s patents and sketches reveal the numerous inventions she designed for the photography industry. Fia Backström’s composite essay On the Photographic—the Growth and Its Perennials performs a dialogue between her text and images, while a framed draft of Abbott’s 1946 “Statement in Regard to Photography Today” is flanked by two of her photographs. Mika Rottenberg’s video choreographs the physics of moving bodies in a projection embedded within the wall, and Abbott’s photographs for the Physical Science Study Committee are compiled into a slide show. As MPA’s aerial photographs of Peru’s Nazca Lines geoglyphs capture the unresolved mystery of this cosmic phenomenon, a set of Abbott’s astrology charts reveal her personal curiosity about the impact of interplanetary forces on her own life.

The bifurcated space of The Earth is a Magnet is based on Hank O’Neal’s explanation of Super Sight’s architectural mechanics. This invention symbolizes the driving force behind Abbott’s explorations with photography: her pursuit of realism. In her 1942 application to patent the Super Sight invention, Abbott explains that “its prime advantage is greater realism, the raison d’etre of photography.”1 For Abbott, realism was the hallmark of photography. It was also the hallmark of the photographer herself. “The camera sees reality, insofar as the photographer is capable of understanding reality, and is a tool par excellence to project reality.”2 In much of her writing, Abbott articulates how her work pairs the civic responsibility of documentary with the intimate perspective of the photographer’s creativity. Perhaps it is in these elucidations that she relays a key to the deferential qualities of her work. In a draft for her 1953 essay “Civic Documentary Photography” Abbott defines the uniqueness of this form: “It seeks to reach the roots, to get under the very skin of reality. Because of its emphasis on realism, documentary photography has an intimate and organic relation with its subject matter.”3

For all of her desire to reveal truths, Abbott withheld significant information about herself from her audience. There are numerous references saved in her archives to her possible political affiliations: documents from the Photo League, newsletters from the Women’s Liberation Movement. Her connections to these groups are inconclusive. During my research, I would sequester myself at the large tables where Abbott’s archives were held, surrounded by boxes of her papers. I tried to “get under the skin” of her files. Poring over letters she carefully penned to her friends or notes she quickly scrawled to herself in the margins of sketchbooks, I searched for an intimate understanding of Abbott’s perspective. But when it came to revealing the links between the personal and political, Abbott stoically denied access. From the evidence of extensive research that Abbott’s biographer, Julia Van Haaften, generously shared with me, I can see how many leads I only grazed in my three years of digging through Abbott’s papers. But even my cursory research reveals an important clue in Abbott’s refusal, providing some understanding about the position she chose to occupy.

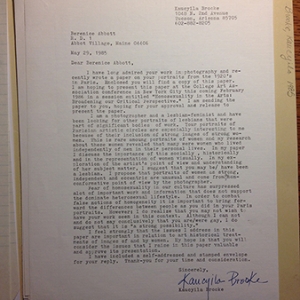

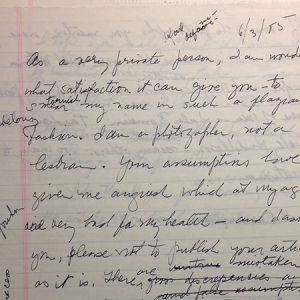

In the Abbott papers at the New York Public Library, I read a draft of a letter that Abbott carefully saved: her reply to a request written in 1985 by the photographer Kaucyila Brooke, which is also included in the same folder.4 Brooke asked Abbott for her approval to present a paper on Abbott’s work in a panel, “Homosexuality in the Arts: Broadening Our Critical Perspective,” at the 1986 CAA conference. Brooke’s paper was entitled “Self-Possessing Realism”. Previously in her own photography, Brooke had learned the dangers of outing people without their permission. She was aware that Abbott—by then in her mid-eighties—had lived her entire life without publicly revealing her sexuality. Abbott was outraged by Brooke’s “assumption”, calling it “flagrant and libelous.”5 By the accounts of friends and associates, and as evident in much of her correspondence, it is clear that Abbott was indeed a woman who loved women and who partnered with women. Nonetheless, in her letter to Brooke Abbott plainly states, “I am a photographer, not a lesbian.”6 It’s difficult for me to make peace with this statement. It feels riddled with shame, from today’s perspective. What does it mean for an artist so focused on the intimacies of realism and the truths of documentary to deflect this essential personal and political position? I can understand the necessity for Abbott to work against the margins that she was already forced to occupy as a woman struggling to have a successful career in the mid-twentieth century, especially considering the populist strain of her work. However, there seems to be more to her statement than just its pragmatism. I wonder whether Abbott’s refusal to acknowledge specifics about herself somehow relates to the deference that I admire in her work. If so, its connection to fear and denial is troubling. And I am confused as to how—in the face of this negation of herself—her work still appears bold, proud, and declarative.

When I am able to view Abbott’s choices without the privileged perspective of history’s judgment, it stirs a tremendous empathy in me. Denying oneself creates a deferential position that—though painful and problematic—is both a confession of human nature and recognition of existent power struggles, and it has its own strengths and resiliencies. I cannot presume to understand how powerful the obstacles and threats may have felt to Abbott in her lifetime. Even in my own experience as a woman and a lesbian growing up in a profoundly more liberal climate, I still know too well how insidiously homophobia can take root in oneself, and against oneself. Likewise, the struggle for women to receive equal recognition and value in the art world continues today, a fact that has loomed resiliently in my peripheral vision throughout my art career. These circumstances do not compare to the oppression that Abbott lived under as a woman, leftist, and lesbian. Abbott came of age before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, and made a name for herself as a photographer during McCarthyism. By the 1969 Stonewall riots, Abbott had already moved to Maine after living in New York for thirty years with her partner, the writer Elizabeth MacCausland.

Abbott’s statement to Brooke was a declarative refusal, yet also illogical. The two identity categories that she contrasts—photographer and lesbian—are not mutually exclusive. This paradox is a reveal. Abbott is said to have made a similar declaration when she applied for work with the Works Progress Administration. As she showed an editor some of her photographs taken on the slum streets of New York City’s Bowery, he commented to Abbott, Nice girls don’t go to the Bowery.” To which she famously replied, “I am not a nice girl, I am a photographer.” For Abbott, being a photographer was how she was able to be everything else: writer, inventor, author, activist, teacher, woman, and lover. When I think of Abbott sublimating her private self into her photography, it reveals a new strength in the work. Rather than leading with individualist heroics, hers is a proud position of bearing witness. I love the contradiction here, as witness is commonly considered a second-class status of subjugation, something that is foisted on one, rather than a choice. For centuries it was the only option available to women who may have wanted to act but were refused. Even to witness is to be involved and to effect change, albeit indirectly.

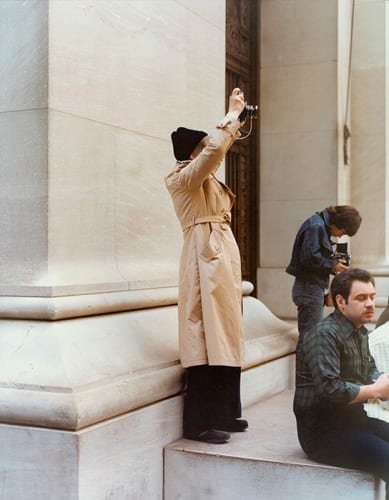

As it masks the face and distracts the body in the solitary act of taking a photograph, a camera can offer its photographer the position of removed observer. Occupying this position is not inherently an act of bearing witness. Abbott’s use of photography extends beyond her body’s relationship to her subject through her camera. Her agential witness can be found in all aspects of her art practice. Abbott turns her observation into action through her historicizing of Atget and other photographic precedents, her civic engagements through science and street photography, and her DIY technological innovations. By employing what was immediately within her reach, Abbott uncovered new ways of connecting, understanding, and translating what she saw. Like her Super Sight apparatus, Abbott’s witness was a negotiation between interior and exterior spaces. To be a witness is not to deny oneself rather it is to acknowledge the impact experienced on oneself. One cannot bear witness without using one’s own body or speaking with one’s own voice. Abbott has written, “The function of photography for Civic Documentary History is to record, to interpret, to comment.”7 When one bears witness, one is able to see and hear oneself oneself among and through others, as well as to acknowledge the impact that others may have. I recognize myself in the deferential position of witness that is characteristic of Abbott’s photography. This is the generosity of her work. It makes space for others to inhabit.

Hank O’Neal, Berenice Abbott Traffic Project, Wall Street, New York City, 1977 (photograph © Hank O’Neal)

Anna Craycroft has had solo shows at Portland Institute for Contemporary Art in Portland, Oregon; Ben Maltz Gallery at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles; Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas; Tracy Williams Ltd in New York; and Le Case del Arte in Milan, Italy. She has had two-person exhibitions at Redcat Gallery in Los Angeles, Sandroni Rey in Los Angeles, and Fundacio Miro in Barcelona. In November 2016, the artist debuted a major new commission, The Earth Is a Magnet, as part of the ICA Boston exhibition, The Artist’s Museum. Notable group exhibitions include Champs Elysees at Palais de Tokyo in Paris, France, and MoMA PS1’s Greater New York 2005. She has also received commissions for public sculpture from Art in General, New York; Socrates Sculpture Park, New York; Lower Manhattan Cultural Center, New York; and Den Haag Sculptuur, The Hague, Netherlands. Artist’s website: http://annacraycroft.com.

- Berenice Abbott, Projection Photography Patent Application, Undeveloped Patent Ideas, Box 10, Folder 8, Berenice Abbott Papers, New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts ↩

- Berenice Abbott, Statement in Regard to Photography Today, Box 25, Folder P,Berenice Abbott Collection, MIT Museum (Gift of Ronald and Carol Kurtz) ↩

- Berenice Abbott, “Civic Documentary History,” Proceedings of the Conference on Photography: Profession, Adjunct, Recreation (New London, CT.: The Institute of Women’s Professional Relations, 1940), 71. ↩

- A final typed draft of the letter was ultimately sent from Berenice Abbott to Kaucyila Brooke. Brooke discusses and publishes the letter and an image of it in her essay “roundabout,” published in The Passionate Camera: Photography and Desire, ed. Deborah Bright (London: Routledge, 1998). ↩

- Berenice Abbott, Draft of Letter from Berenice Abbott to Kaucyila Brooke, Box 2, Folder 5, Berenice Abbott Papers, New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Berenice Abbott, “Civic Documentary History,” Proceedings of the Conference on Photography: Profession, Adjunct, Recreation (New London, CT.: The Institute of Women’s Professional Relations, 1940), 71. ↩