Roberto Visani, hot plate, 2016, cast iron, bricks, stone, 5 x 17 x 12 in. (12.7 x 43.1 x 30.4 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

“How can colors that don’t have a name start a conversation?” –Roberto Visani, 2016

In September, I went to meet Roberto Visani at his temporary installation at 21ST.PROJECTS, an art space in the apartment of the critic and curator Saul Ostrow in New York City. The six new drawings on the wall and two small found-material sculptures were almost incognito within the apartment’s setting. In seeing this new work, it was clear that his practice had evolved into working on a much larger scale and that the artworks begun to hang further off the wall—each becoming more of an object than a drawing. Filled with books and chairs and flooded with light, the space was well-suited for sitting and having a conversation.

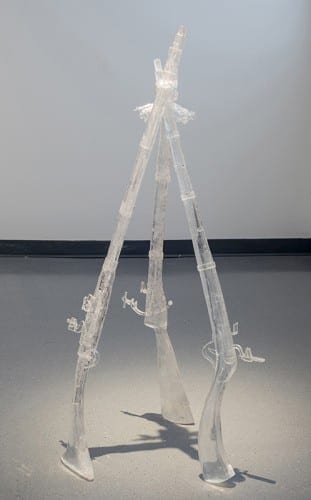

Roberto and I started talking about the work that he had begun during his fall 2015 residency at Guttenberg Arts, and Guttenberg’s printmaking facility. He had been actively looking for a residency outside of the city with full access to equipment that he would not have otherwise. Visani has a seasonal method of working, creating sculpture outside during the warmer weather and paperworks indoors during cold weather, which is something he was able to continue while in residence at Guttenburg Arts because of the residency’s large backyard area for artists to use. In the fall through to the winter, when the weather allowed, he poured sculpture molds for a new series of iron gun sculptural works outside then stockpiled his printmaking experiments inside that he made during the colder months. His printmaking also became experimental as he cultivated a working method of pushing conventional ideas of perfect editions and focused on an evolution of the multiple waiting to be deconstructed.

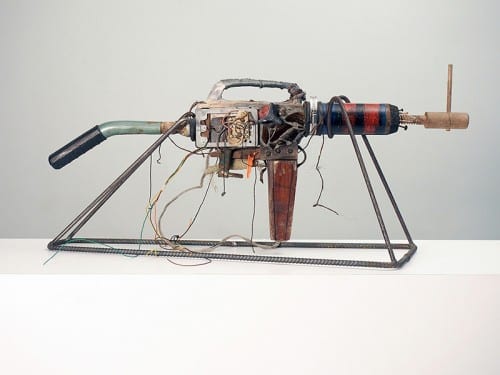

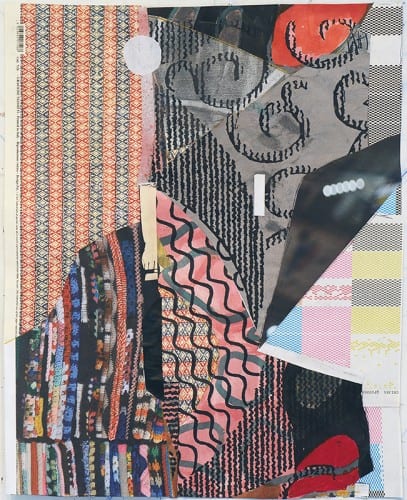

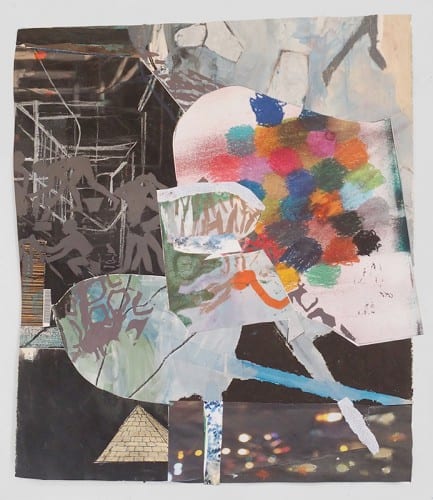

Through this method of working, Visani created an archive from which he was now pulling to make these new works of art. The formal aspects of his work also changed. The color palette that he was working with felt like faded documents that had been deconstructed to their barest formal elements, leaving the viewer with an uncanny feeling that one should recognize what was going on. Visani spoke to me about lines—the line of a pencil, the line from a cut, and the lines from a stencil outline. These lines became a mark-making reference to the underpinning story that he is piecing together through his work. These pieces also make up the new sculptural works that are part of an ongoing series of gun-like constructions. They use string and mismatched found-objects collaged together, culminating in something that is familiar and yet completely sum of its parts. When Visani talks about the colors, he has no name for these in between colors. They are sort of like one but not quite another. He aims for that ambiguity and leaves us with the work.

The conversation that follows took place in spring and fall 2016.

–Caitlin Masley-Charlet

Roberto Visani, automatic weapon, 2015, wood, metal, plastic, glass, found objects, 17 x 31 x 5 in. (43.1 x 78.7 x 12.7 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Caitlin Masley-Charlet: You’ve often said that you are constantly focused on putting the time in at the studio that it takes to make your work. How did you develop your specific creative process, and how has it changed over the years?

Roberto Visani: I’m a tactile thinker, and I tend to be attracted to accessible materials. I have this idea of being multifaceted, so I am actively looking for new ways to express myself. When I began making art as a student in the 1990s, I was more focused on creating cohesive series of works but I am less concerned with that now. A series happens naturally whenever I engage with a question or multiple questions over a period of time. Sometimes my creative inquiry results in a singular work and I move on.

Masley-Charlet: Your process takes time to explore various materials first, and then you develop a series of works. But what happens in the meantime? How do you sustain your art practice when you spend months creating new works?

Roberto Visani, half the story has never been told, 2015, clear acrylic, 47 x 22 x 22 in. (119.3 x 55.8 x 55.8 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Visani: As an artist, I’m engaged in the creative process on a day-to-day basis. However, art practice to me implies the professional side of things—anything from applying for grants to documenting artwork. I would rather focus all my attention on making the art, but it’s important to attend to the professional side of things to build my career. I look for opportunities, whether residencies, grants, or exhibition venues. Seeing my work within a professional context such as an exhibition or reproduced in an article helps me to understand its relationship to an audience. My goal is for my work to communicate to a broad audience.

Masley-Charlet: These professional opportunities don’t always pay the bills. Do have an additional income or art-related job, and do you consider it a part of your practice?

Visani: I’ve taught studio art at John Jay College in New York since 2004. At first, teaching felt distinct from my creative practice. Over time, I have been able to see how ideas in my studio cross into the classroom. Teaching causes me to be conscious of the way I make art, so that I can share relevant aspects of the creative process with my students. I know this sounds cliché, but I feel any activity can be “artful” when we create a dialogue between the components of a situation. In that sense, teaching is a creative act that absolutely aligns with my practice.

Roberto Visani, In Medias Res, installation view, Guttenberg Arts, Guttenberg, New Jersey, 2015 (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Masley-Charlet: You reference residencies as a method to build your career—what led you to first apply to your first one?

Visani: The first residency I applied to was Atlantic Center for the Arts in Florida. I was in my last year of graduate school at the time. It seemed like an excellent opportunity to work outside my comfort zone, and meet a community of artists outside of an educational context. At the residency, everyone was interested in moving their work in a new direction. This is still what interests me about residencies: the combination of place and participants within the residency experience, and how that affects the artwork I create.

Roberto Visani, Travel Fox, 2015, mixed-media collage, 20 x 16 in. (50.8 x 40.6 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Masley-Charlet: What is your comfort zone? Is it a place, like a permanent studio, or a daily routine?

Visani: By comfort zone, I mean my routine in my permanent studio. I have a level of flexibility and privacy there that is difficult to replicate in a residency program. Residencies serve a different purpose for me: since a fixed amount of time is inherent to residences, I approach the experience with a concrete goal in mind.

Masley-Charlet: Did your first rejection from a residency motivate you to keep applying for more?

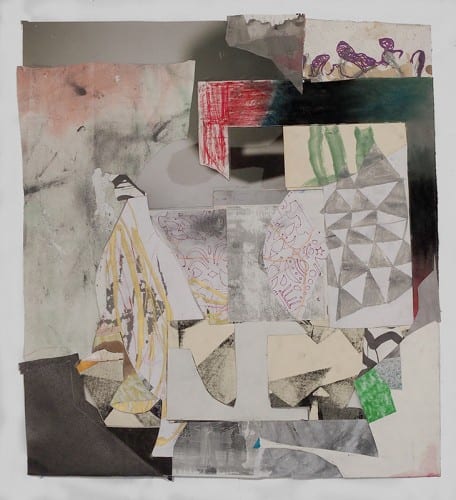

Roberto Visani, event horizon, 2016, mixed-media collage, 26 x 23 in. (66 x 58.4 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Visani: I applied for my first residency, Atlantic Center for the Arts, while I was still in graduate school at the University of Michigan. In beginning, I was lucky—I was accepted into the first two residencies I applied to. I’ve had mixed results since then. There is a high rate of rejection in our field, and the challenge is to not take the rejection personally. If a residency program doesn’t think my work is deserving of the opportunity, I know another will.

Masley-Charlet: Did you initially learn about residencies from fellow artists, or were certain ones already on your radar? What did you look for when applying to residencies?

Visani: Since graduating in 1998, I have done eight residencies. The first ones I applied to were based on getting more exposure, like the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Workspace residency. LMCC provided studio space for nine months, and there were thirty artists in the program, working in a variety of media. We had studio visits once a month with curators, gallerists, and other art-world professionals. Toward the end of the residency, they organized an open studio event that gave us a chance to share our work with the public. In general, most of the residencies I’ve done have been in New York (where I live), but my favorite residency experiences have been away from home. I like that I don’t have the normal distractions, and it is easier to get to know the other artists because you socialize together more. I also have been interested in residencies that allow me to engage a process that I do not normally have access to, like printmaking or metal casting.

Roberto Visani, ‘The king is not dead’, 2016 mixed-media collage, 38 x 38 in. (96.5 x 96.5 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Masley-Charlet: Do you have any plans to be in residence at programs that offer these sorts of facilities?

Visani: I am currently applying to printmaking residencies at the Lower East Side Printshop and Robert Blackburn studio at Elizabeth Foundation Association, both of which are located in New York, and am also interested in the Kohler Arts/Industry residency in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. These three residencies offer facilities that I do not have access to in my home studio, but that are important to my work. This summer, I will be in residence at Franconia Sculpture Park in Shafer, Minnesota, to create a large public sculpture in cast iron—something I’ve wanted to do for some time.

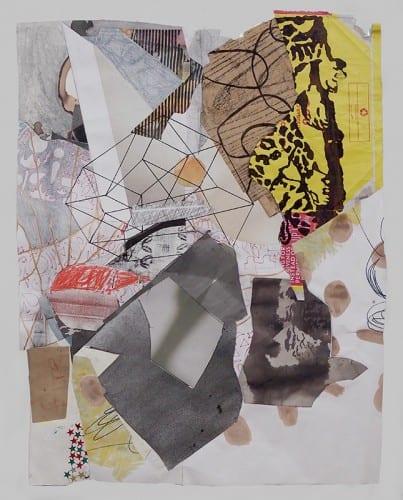

Roberto Visani, Shadows and Mirrors, 2016, mixed-media collage, 30 x 27 in. (76.2 x 68.58 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Masley-Charlet: If you are in search of facilities and access to new methods when considering a residency, what interested you about Guttenberg Arts?

Visani: Guttenberg Arts seemed different than others I had done. I liked that it was on a smaller scale, and that the program offered a solo show and financial support. The program and staff were nurturing and supportive, which was important to me. The most impactful part of the residency was the printmaking facilities. For several years, I’ve created collage drawings that incorporate found printed matter. I have been interested in creating my own prints, and using them in my collages. Combining screen printing with other drawing methods has served as a way of extending my collage practice through scale, color, and texture.

Roberto Visani, Stack, 2016, cast iron, 74 x 40 x 13 in. (187.9 x 101.6 x 33 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Masley-Charlet: Has your process changed since you’ve been at Guttenberg Arts? Can you talk about the work that you made?

Visani: Using screen printing and the printing roller to generate imagery for my collage drawings has been a fantastic new development. It has extended the range between mass and atmosphere within my collages. The works have become a mediation on guise and individuality, investigating the liminal space between self and surroundings. It will take some time for me to understand the relationship between the printing processes and concept, but the residency has provided a great start.

Roberto Visani, Paterson Stack, 2016, cast iron, 45 x 22 x 12 in. (114.3 x 55.8 x 30.5 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Masley-Charlet: What is the importance of an artistic community to you, and has it changed over the years? Have you been asked to join a post-graduate school critique group?

Visani: Artists tend to support each other from a mutual understanding of the challenges we face—whether it is the cost of studio space, busy schedules, or competition for opportunities. The most meaningful relationships I have with artists are not about the next exhibition or professional opportunity, but are about our studio practices. From time to time, my friends and I visit each other’s studios, and I enjoy it. It’s an important source of support. I’m grateful for the access I have to so many committed art professionals by living in New York. I always feel challenged to pursue my artistic goals, to make the best work I can, and to dedicate myself to my practice.

Masley-Charlet: How do you sustain the creative part of your practice, and has it developed over the years since you graduated?

Roberto Visani, subsets, 2016, mixed media collage, 30 x 37 in. (76.2 x 93.9 cm) (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Visani: Like most artists, I have a day job so I have to balance my studio schedule around my work schedule and other life responsibilities. I have to stay engaged on a daily basis. Even if I have been at my job from early in the morning to late in the evening, it helps if I spend a little time in the studio to stay connected to my artwork.

Masley-Charlet: You spoke earlier about being in contact with an audience, and at Guttenberg Arts, we bring in visiting critics who are often curators. Do you think this access to visiting critics is important?

Visani: The artwork we produce needs an audience, and curators, gallerists, and critics help artists connect art to a larger audience. I have had some studio visits that functioned as a introduction to what I do, and others when the subject matter and formal qualities of my work already overlapped the interests of my visitor. I like when someone has been to my studio previously returns, because the dialogue continues to develop over time.

Masley-Charlet: How can Guttenberg Arts and residencies in general support more experimentation? Specifically, do you feel like it is a safe place to fail?

Visani: Experimentation is really important, but it’s not as organic a process in a residency that is open to the public. The privacy of my home studio helps to create a judgment-free space. While there are times for editing in my home studio, in a residency the editing is a more active part of the process because of the exposure. At one residency I did, there was a lot of visibility, and the residents treated the open studio at the end like gallery space instead of a working space. Based on that experience, I thought the professional goals were prioritized over the studio practice.

Roberto Visani, “You see the hut yet ask, ‘Where shall I go for shelter?’”, 2016, bamboo, steel screw eyes and plastic zip ties, Braddock Park Art Festival, North Bergen, New Jersey (artwork © Roberto Visani)

Masley-Charlet: Do you think that residencies should make more connections to museums, galleries, curators, or historians?

Visani: It depends. A few museums offer residencies, and some residencies are set up to introduce artists to other arts professionals. Others are focused on seclusion and getting a lot of work done, and some are both. I think there should be a mix, so that artists can apply to whichever best fits their goals.

Roberto Visani is a multimedia artist residing in Brooklyn, New York. He has exhibited his work internationally in such venues as New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York; Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; Bronx Museum of Art, New York; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; Contemporary Arts Center, Cleveland, Ohio; Barbican Galleries, London; and Ghana National Museum, Accra, Ghana. He has been awarded artist residencies from institutions including the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council New York; Henry Street Settlement, New York; and Art Omi, New York. He is a former Fulbright Fellow to Ghana and NYFA Artist Fellow in Sculpture. As part of his Fulbright activities, he began creating his iconic gun sculptures. These works have been reviewed in such publications as the New York Times, Art Forum, Art News, and Frieze. Since 2004, Visani has taught at John Jay College, CUNY, New York, where he is an associate professor of art.

Caitlin Masley-Charlet is a Brooklyn-based visual artist working in drawing, installation, and sculpture, and the deputy director of Guttenberg Arts in Guttenberg, New Jersey. She holds a MFA from the University of Arizona and a MS in design and urban ecology from Parsons/The New School. Her work has been exhibited in group shows at MoMA/PS1, Long Island City, New York; Center for Built Environment, Berkeley, California; and Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York. She has had site-specific solo exhibitions at McColl Center for Contemporary Art, Charlotte, North Carolina; Islip Museum, East Islip, New York; Urban Institute of Contemporary Art, Grand Rapids, Michigan; HVcc Foundation, Troy, New York; Kingston Museum of Contemporary Art, Kingston, New York; and the HDLU Museum, Zagreb, Croatia. Masley-Charlet is also the founder of studioMAPstudioSWAP, which is part of the Parsons/DESIS Lab/CSI Incubator program.