A training session at the Art+Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon. Four sessions led by experienced Wikipedians were offered throughout the day. (photograph © Chelsea Spengemann)

Does Wikipedia need us more than we need Wikipedia? As the seventh-most-widely-used website in the world, it is clearly thriving as the most globally accessible, nonprofit source for information online. The site has made a mess of our traditional idea of knowledge, but over the past few years it has been embraced by many academic and cultural institutions. In its ideal state, Wikipedia is a free, continuously reorganized, multilingual, crowdsourced, and nonlinear library1 that points readers to the newest, popularly agreed-upon, and verifiable research on any given topic. To achieve this ideally would require everyone’s attention, constantly. This is where the trouble starts, but it is also what makes Wikipedia irresistible. The diversity of labor required to feed and maintain such a beast feels impossible, yet we exhaust ourselves for the potential future return—it reminds me of mothering.

As a privileged, overwhelmed mother living in Brooklyn who is also trying to establish a curatorial practice, the work I take often depends on paying a sitter about the same wage I might be earning. I accept the near-even trade because I value the intellectual engagement my work offers. I depend on it the same way I depend on childcare. Why did I have two kids if my dependency excludes them? In other words, they need me, but did I need them? And so too, with Wikipedia.

Art+Feminism representatives answering questions. Volunteers were identified by green bandanas. (photograph © Chelsea Spengemann)

Since the Wikimedia Foundation (the nonprofit entity responsible for operating Wikipedia since 2003) published a 2010 study showing gender bias2 on Wikipedia, its survival has depended on recruiting a more diverse population of volunteers. Art+Feminism is one impressive initiative founded in response to Wikipedia’s demands. Since 2014 it has organized edit-a-thons at multiple, international venues, that are centered on the theme of women in the arts. This year’s main event was held on March 5, 2016 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York3, and focused on intersectional feminisms, reflected in sessions on LGBT organizing and gender identities on Wikipedia, as well as in the partnering with AfroCROWD. The event at MoMA was one of about 125 organized by Art+Feminism that weekend; every year this number has roughly doubled. This year’s gathering at MoMA began with a conversation on contemporary feminisms and digital culture led by MoMA’s director of digital content and strategy, Fiona Romeo; writer Orit Gat; artist and activist Reina Gossett; and New York Times technology columnist Jenna Wortham. All contributors defined their work within a digital, feminist space and, through the invaluable anecdotes that such panels permit, conveyed an urgency for intersectional feminist action not only online but also on the street. As Gossett noted with excitement, the edit-a-thon was an activist space. Judging by the energy in the room full of eager participants, that is exactly what had brought us there.

Left to right: Museum of Modern Art Director of Digital Content and Strategy, Fiona Romeo, with writer Orit Gat, New York Times technology columnist Jenna Wortham, and artist and activist Reina Gossett during the Art+Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon opening conversation on contemporary feminisms and digital culture, held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, on March 5, 2016. (photograph © Chelsea Spengemann)

The communal gatherings known as edit-a-thons are crucial for Wikipedia’s future. Editing tutorials are available online, but there is tremendous value in gathering in person. As with any online community, myriad norms must be followed by participants, but learning them takes time. One benefit of attending an editathon is it functions as an introduction to these norms so you can make your first edits with confidence. One such insight is that Wikipedians embrace anonymity in usernames but are transparent regarding the editor’s connections to particular topics4. Unlike on Facebook and Google, your full name is not required to participate on Wikipedia, nor is your gender. As one Wikipedian, Lane Rasberry, pointed out in his impassioned talk at the edit-a-thon about the unparalleled collection of LGBT resources on the platform, Wikipedia does not track what pages people read or the reader’s physical locations. Rasberry asserted that Wikipedia is the world’s most consulted source of information, and a vital resource for communities who struggle with representation in popular media. He cited his own experience growing up in rural Texas and being told that there was no one else like him, and reminded participants (with a smile) that not everyone lives in New York City. Rasberry presented the LGBT Portal as an example of what is possible through active engagement with the platform. He also pointed out how the transparent process by which articles are edited (see the “talk” tab on any Wikipedia entry) fosters collective education. His example of the type of culturally important, messy work unique to Wikipedia was the one thousand-plus pages of discussion around the pronoun to use to identify Chelsea Manning prior to her public gender transition. If the topic is timely enough, generative conversations will happen and will remain on the page for future study.

Wikipedian Lane Rasberry’s session on LGBT projects was one of four breakout sessions that happened over the course of the day. (photograph © Chelsea Spengemann)

Another tip gleaned through the casual discussion the edit-a-thons foster is that one is better off searching Wikipedia through Google rather than directly typing your query into Wikipedia itself. If you need something in particular—say Art+Feminism edit-a-thon outcomes—enter that subject into Google and you get a direct link to the information found on Wikipedia5. Rasberry raised the point that the two entities clearly have a close relationship, because Google consistently delivers content from Wikipedia above almost everything else. A large part of the shift in trust in Wikipedia seems to be driven by Google’s trust in the source. How one is represented on Wikipedia, if notable enough to be there, is becoming as important as one’s presence on Google, if not more.

Participants working in the Museum of Modern Art’s library and archive. A reference librarian and trained Wikipedeans were available for questions. (photograph © Chelsea Spengemann)

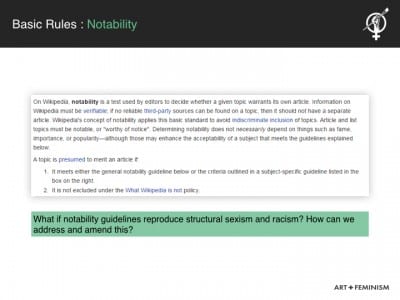

To appear on Wikipedia, an artist must pass the platform’s standard of notability, one of several guidelines for adding an entry. To qualify as notable, the artist must have proof of significant coverage in a reliable source and proof that their work is in the permanent collection of a major museum. All of this information must then be entered by someone without a conflict of interest. As many participants are quick to realize, Wikipedia guidelines like these are problematic in that they reproduce the exclusionary tendencies already in place in the art world (and most other fields). One question raised by Art+Feminism at the edit-a-thons is how, as it’s phrased it in one of their slides, to “address and amend this.” Representing the diversity of the world starts with documenting that diversity, or as Gat proposed in the MoMA conversation, perhaps simply reorganizing the existing documentation. The question was barely addressed at this year’s event, but it is certain to reappear.

Art+Feminism Training Slide on Notability, available to download on Wikipedia. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Meetup/

ArtAndFeminism/Resources#Meetup_organizer_materials

Though interest and belief in Wikipedia as a legitimate source of information is real, the sustainability of the volunteers ushered in through edit-a-thons remains to be seen. I am a woman who values physical presence over mediated exchange, so I have not been inclined to participate in online communities, nor have I ever sought out crowdsourcing projects (though I have certainly benefitted from them). So how did I get to Wikipedia, and will I stay?

It all goes back to childcare. If you are a primary caregiver and you are also something else, your existence for at least a decade of your life revolves around childcare so that you may pursue your “something else.” When I saw that the Art+Feminism Wikipedia edit-a-thon provided free childcare services for participants, I read “free childcare” and registered for the event6. Feminism is something that I relate to differently since becoming a mother. I rely on my community of mothers to survive the intensity of being one. Inspired by Art+Feminism, as I headed into the edit-a-thon I asked myself what (aside from the information I’m inclined to hoard as an art researcher) might I contribute about being a mother on Wikipedia? When will I make time to say it?

Participants with children during a lunch break. Food, drinks, and childcare were paid for through a grant provided by the Wikimedia Foundation. (photograph© Chelsea Spengemann)

“The reason women don’t contribute to Wikipedia is that we have more pressing things to do. I would love to elaborate, but I have to finish the laundry, pay the bills, feed the cat, clean the apartment, and do the meal planning and grocery shopping before I head off to work.”7

Despite my identification with the sentiment put forth by the commenter above, I firmly believe it is time to add “edit Wikipedia” to our list of non-market activities. If we have time to post a comment or time to read an article, we have time to contribute to Wikipedia. It can be that easy. On the inspiring list of Art+Feminism events that took place over the weekend of March 5th, I found a link to a group called “mom artists” in Brooklyn that is “focused on all gendered primary caregivers who make art.” Is this the beginnings of a Primary Caregiver Portal? If Wikipedia needs it, ultimately, so do all of us8. It is time to acknowledge that there is much at stake in what information is distributed online, and it’s time for everyone to contribute, especially if you have experience with an underserved community, and especially if you have access to education. As fully as we nourish Wikipedia, it will nourish us in return.

Chelsea Spengemann is an independent curator who earned an MA from Purchase College in 2011 and an MFA from the ICP-Bard Program in 2005. Her exhibition The Instant as Image is on view at the Neuberger Museum of Art until June 5, 2016. Past projects include Becoming Disfarmer, an exhibition and catalogue for the Neuberger Museum (2014); …and there’s my marble double, Cuchifritos Gallery (2013); The Tulsa Reader (2011); and FLOAT, Socrates Sculpture Park (2009). Spengemann also manages the estate of the filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek.

- See Griselda Pollock, “Feminism, Art, the Library and the Politics of Memory,” Art Libraries Journal 37, no. 1 (January 2012): 5–12. ↩

- The worldwide study differentiated between readers and contributors. Both groups were primarily male but the contributors “showed a substantially larger share of males than readers.” The study found only 12.64% contributors to be female. The average age of respondents to the study was 25.22 years and only 14.72% of respondents had children. Most respondents were from Russia. Numerous follow-up studies have been done and are still in progress. ↩

- Art+Feminism held its first edit-a-thon in 2014 at Eyebeam Art and Technology Center in New York and thirty other satellite locations. It began working with the MoMA Department of Education through Sara Bodinson, Director of Interpretation, Research and Digital Learning, who is also a member of POWarts (the Professional Organization for Women in the Arts). ↩

- David Auerbach’s series of articles for Triple Canopy detail the history and complex function of anonymity, or what he calls “A-culture,” on the internet. Auerbach states, “A-culture provides an unparalleled space for registering the voices of a class of people who cannot be heard on the more prominent online channels.” He continues, “What A-culture has done, inadvertently, is establish the largest virtual congregation of members of the local class intermixing freely with members of the national class and foreigners. Rural high school dropouts and Harvard PhD students interact often without knowing one another’s background, and the uniformity of the discourse further eradicates distinctions.” The integrity of Wikipedia relies on a certain degree of anonymity among contributors but tracking and maintaining the diversity of such a group is also crucial. ↩

- See Art+Feminism’s response to that query at http://www.newyorker.com/tech/elements/a-feminist-edit-a-thon-seeks-to-reshape-wikipedia, as of April 12, 2016. ↩

- According to Art+Feminism, “The Wikimedia Foundation awarded the project a grant that covered, amongst other things, the food and childcare at MoMA and the many node events,” email conversation with the author, March 8, 2016. ↩

- Alice Henry Whitmore, letter to the editor, The New York Times, February 5, 2011 at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/06/opinion/l06wiki.html, as of March 22, 2016. ↩

- Entries related to mothering and birthing, such as that for “Home birth” desperately need more attention on Wikipedia. ↩