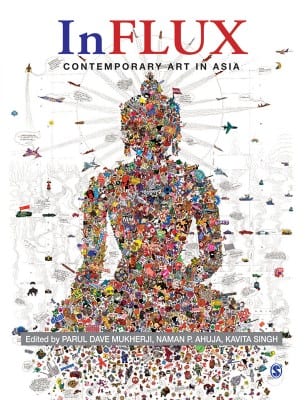

Parul Dave-Mukherji, Naman P. Ahuja, and Kavita Singh, eds. InFlux: Contemporary Art in Asia. New Delhi: Sage, 2013. 288 pp., 112 ills. $36 paper

InFlux: Contemporary Art in Asia is dedicated to the late Jangarh Singh Shyam (1962–2001), an adivasi (indigenous) artist from central India who committed suicide in Japan. Shyam’s life and death epitomize the paradoxes and perils of the globalizing art world. He was discovered by J. Swaminathan, an influential Indian artist and critic who became the director of Roopankar, the art museum at Bharat Bhavan, a cultural center established in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, in 1982.1 Shyam developed an art style based on his imagination, individual memories, and collective myths. His work was shown in the landmark exhibition Magiciens de la terre, curated by Jean-Hubert Martin, at the Centre Pompidou and the Grande Halle de la Villette in Paris in 1989, and in Other Masters: Five Contemporary Folk and Tribal Artists, curated by Jyotindra Jain, at the Crafts Museum in New Delhi in 1998. During a 2001 residency at the privately owned Mithila Museum, which commissions and displays folk and tribal art from India, Shyam hanged himself, allegedly because his Japanese patron denied his requested passage home.2 The website for the Mithila Museum, located in Tokamachi, Niigata Prefecture, Japan, claims: “Unlike in the native environment where these paintings are drawn, in Japan the Mithila and Indian aboriginal groups create their art in an environment where a higher degree of refinement and creativity is possible.”3

Fourteen years after his death, a cottage industry of Gond art has emerged, drawing on Shyam’s distinctive style and employing the artist’s son, Mayank Shyam, and wife, Nankusia Bai, as well as many other adivasi artists in and around Patangarh, Madhya Pradesh, where Shyam was born and raised. The Jangarh kalam (style), as one journalist put it, has been used to sell tribal shows in Paris and children’s books in India, not to mention contemporary art to a growing class of international collectors.4 Rather than being a success story of the art world, the classic narrative of an isolated genius rising against all odds, Shyam’s career highlights hierarchy and inequity. It serves as a cautionary tale of violence and marginalization amid the widespread celebration of a newly global and postcolonial order in the art world.5

Reminding the reader that Shyam was named Jangarh after the jangan (census) officers who visited his village on the day of his birth, the editors of InFlux write: “He was born on the day people in his village were counted and died when he realized that only his paintings counted” (xvii).

By beginning InFlux with an image by and a remembrance of Shyam, the editors Parul Dave-Mukherji, Naman P. Ahuja, and Kavita Singh, who teach in the School of Arts and Aesthetics of Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, signal their commitment to critically examining the effects of globalization on contemporary art in Asia. The book resists a triumphalist narrative of arrival and acceptance, of Asia’s arrival into global art markets and the acceptance of Asian art in an international art world. It also resists an essentializing account of Asia—as a continent or civilization—and instead illuminates contested notions of Asian identity. Hence the editors’ conscious decision to subtitle the volume “contemporary art in Asia” as opposed to “contemporary Asian art.” The former enables a fluid and flexible understanding of belonging to Asia, one that encompasses Marian Pastor Roces’s metaphor of curating barbarians, which is indebted to the Filipino nationalist José Rizal (1861–1896) and the German critic Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), and Rustom Bharucha’s analysis of the civilizational ideals and cosmopolitan identities of Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) and Okakura Tenshin (1862–1913). Such intellectual touchstones—Rizal, Benjamin, Tagore, and Okakura—at once historicize and destabilize what it means to be Asian.

Divided into three sections focused on culture (“Section 1: Contested Terrains and Critical Reimaginings,” edited by Dave-Mukherji), geography (“Section 2: Tropes and Places,” edited by Ahuja), and exhibitions (“Section 3: Interventions in the Public Sphere,” edited by Singh), InFlux begins with a general introduction by Geeta Kapur, a critic and curator based in New Delhi, whose model of socially and politically committed cultural practice has been enormously influential in India and elsewhere. Like Okwui Enwezor and Gerardo Mosquera, Kapur places questions of postcolonial identity and history at the forefront of her curatorial work and thereby of an international art world. In her introduction, she explains how most of the InFlux essays originated from the conference “Elective Affinities and Constitutive Differences: Contemporary Art in Asia,” which was sponsored by the Biennale Society in New Delhi in 2007. The conference, an occasion to ponder the need for an “Asia-centered” biennale in New Delhi, became an opportunity for a “‘considered’ negation” of the project (ix). Kapur understands this negation as the work of critique. Indeed, a dialectical method of viewing art and society is evident in her essay “Curating Across Agnostic Worlds,” which provides a historical overview of the changing role of the curator and postcolonial exhibitions from the 1960s onward.

Reflecting on her practice as a critic and curator in an international field, Kapur contextualizes the explosion of “Southern biennales” since the 1990s within a long history of decolonizing interventions in the art world, from the Bienal de São Paulo, established in 1951, to the Bienal de La Habana and Magiciens de la terre in the 1980s. For Kapur, the goal of exhibitions is to “develop agonistic sets of relationships, where the curator stages the contradictions of the global contemporary, and acting in the manner of a friendly ‘enemy,’ makes the symbolic space that artworks inhabit more adversarial” (175, emphasis in the original). Such curating complements the work of the artist, a figure who is “always situated, but also always liminal to the established order of things, both at once, and therefore peculiarly placed to question the hegemonic tendencies of national and global, ethnic and imperialist ideologies” (176, emphasis in the original). This utopian notion of art and the artist is a consistent thread in Kapur’s writing since the 1960s, evident in her remarkable essay In Quest of Identity: Art and Indigenism in Post-Colonial Culture with Special Reference to Contemporary Indian Painting.6

Many of the contributions to InFlux share aesthetic and political solidarities with Kapur, particularly in their focus on curating as a creative and ethical act. The figure of the curator emerges as at least as important as the artist in the contemporary art world, and the role of the curator is understood expansively and imaginatively. Consider Pastor Roces’s evocation of an “Asian barbarian” who “is obliged to take up the word curator to contaminate a precious art world category, transmogrifying it to evoke a multitude of acts: prompting laughter, unease, and metanoia in the play amidst powerful and weak languages; perceiving and circulating visual forms for cross-infiltrations of networks; contriving event thresholds that recombine metaphoric traditions; proliferating a barbaric artist/curator creature for as [sic] contagion” (63–64). Her charge to “curator barbarians—barbarians who curate and curators who take on barbarians” is “to neither indulge in exceptionalism nor slip into reduction, provided that the assertion is grounded in the specific character and order of heterogeneity in Asia” (63).

In a similar spirit, Arshiya Lokhandwala proposes that Asia is “a useful construct” to critique the current order of globalization and examine its effects across diverse areas of the world (42). This ambivalence toward and skepticism of Asia as a stable ground or geopolitical truth—and therefore as the basis for scholarly or artistic inquiry—extends across the essays. Gayatri Sinha analyzes the map and globe as metaphors in contemporary Indian art that imagine a terrain extending from Baghdad to Bharat [India] and recall historical models of imagining Asia, from the travel accounts of al-Biruni (ca. 1030) to painting in the court of the Mughal emperor Jahangir in the early seventeenth century (51). For Sinha, these metaphors have emerged in a new age of empire as “cartographic necessities” (49). Shaheen Merali discusses the exhibition he organized in Madrid in 2009, Indian Popular Culture . . . and Beyond: The Untold (the Rise of) Schisms, which probed the boundaries of India, Asia, and the world through the lens of popular culture. With the exhibition, he aimed “to start the uncoiling of this aspect of Indian culture—which has so attracted outsiders,” and in so doing, remake territories, geographies, and identities (184).

Oscar Ho Hing-kay and Charles Merewether vividly sketch the function of the curator as creator and conscience, alternately interventionist and witness-observer. Ho discusses the reification of Lo Ting, a mythical amphibian and a metaphor for the city of Hong Kong invented in and through exhibition practice, and highlights the powerful effects of exhibitions in creating place and society rather than merely reflecting them. Mimicking the display strategies of history museums, Ho presented Lo Ting in an exhibition about the history of Hong Kong on the eve of its handover to China in 1997. What began as “a fabrication of Hong Kong history” was eventually adopted into the curriculum of secondary schools as “local history” (229–30). For Ho, this process represented “a collective creative act against hegemonic domination” (231). Merewether reflects on the aestheticization of politics in photographs of the victims of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge regime displayed at the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide (the erstwhile high school–turned–concentration camp S-21 prison) in Phnom Penh, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. While Ho contemplates fakes exhibited in a history museum, Merewether asks us to consider how truths are displayed and viewed in diverse institutional frameworks, including in a history museum claiming to remember the dead, both documented and undocumented (twenty thousand prisoners were held in Tuol Sleng; photographs of seven thousand survive). Highlighting an intimate if fraught relationship between archives and museums, Merewether discusses theories of trauma, testimony, and truth, and performs the role of curator as cultural critic, citing the intellectual and ethical examples of Benjamin, Emmanuel Levinas, Michel Foucault, and Giorgio Agamben.

InFlux offers an unusual view of the art world from Asia, with many contributors located in India and others based in Kazakhstan, Pakistan, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Australia, Germany, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States. China is largely absent from the volume, though some contributors, notably Kapur and John Clark, frame their projects within the context of the spectacular rise of Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. Indeed, one can view the volume—and the 2007 conference from which it arose—as a challenge to the hegemony of Western and Chinese art in the contemporary art world. Even as many scholars have turned their attention to globalizing processes in the art world, scholarship on contemporary art tends to focus on practices and practitioners situated in the West. The discourse on globalization and contemporary art is still dominated by views from London and New York, or Basel and Berlin, and occasionally reflects biennales elsewhere—in Guangzhou, Shanghai, Beijing, or Singapore, for example—with relatively few critics and scholars attending to the problems of art making and exhibitions in cities without biennales, or nations without established systems of patronage for art.

What does it mean to be an artist, critic, curator, and citizen in Almaty, Beirut, Tehran, Lahore, Mumbai, Phnom Penh, and Bangkok, to name some of the locations examined in the volume? The answer, more often than not, is contingent on practices and discourses in Cambridge, Amsterdam, New York, Madrid, and Paris, as the essays by Clark, Kapur, Merali, Negar Azimi, Quddus Mirza, and Valeria Ibraeva suggest. Artists and artworks circulate in networks that extend across Asia and the world, and these networks are constituted and constrained by relations of power. At a video art exhibition in Tehran in 2005, where the work of eight young artists was on display in “a small independent gallery,” Azimi wonders whether the “artists have been up late watching Shirin Neshat, an Iranian artist living in America,” whose work is “very dramatic, very Manichean, very East-meets-West in uncomfortable fashion,” and highly successful in the art world (97). Mirza considers how contemporary artists from Pakistan such as Rashid Rana, Hamra Abbas, Imran Qureshi, Jamil Baloch, and David Alesworth mobilize tropes of beauty and violence to represent the nation. In order to meet the demands of an international public, Pakistani artists, according to Mirza, must produce work that corresponds either to the “beautiful art of miniature making” or to spectacularized “images of violence and terror” (91). In Kazakhstan, Ibraeva argues, contemporary art is “largely an export product,” and in the 1990s the media often described artists as “‘troublemakers,’ ‘hell-raisers,’ and ‘CIA agents’” (141, 137). Referring to Kazakh exhibitions in 2003 and 2004, she notes the return of “a heightened exoticism with camels, yurts, and the distant steppe” despite trenchant critiques by artists and critics of the idealizing images associated with Soviet and post-Soviet official mythmaking (143). Collectively, the Asia conjured by these contributors is transnational and transcontinental, a complex product of cultural and commercial exchanges with the West and other regions of the world such as Africa and Latin America.

InFlux’s conceptualization of Asia is different than that of the US academy, which divides the continent into geopolitical regions of South, Southeast, Central, East, and sometimes Northeast Asia (West Asia, in the US context, is still studied under the rubrics of the Middle East or Near East, though the Far East as a category has largely disappeared from critical academic discourse). One measure of this difference lies in the essays by Azimi, Ibraeva, Mirza, Ranjit Hoskote, and Nancy Adajania that focus on problems of religion and secularism in India, the imaginative geography of Islam, cultures of nomadism and nationalism in post-Soviet republics, and the global landscape created by the US-led war on terror. To counter stereotypical images of Asia as “the Silk Route, the Rice Bowl, or the Mega-city” in contemporary exhibition practice, Hoskote excavates a history of the “Far West” and evokes an image of “the House of Islam,” casting it as “a spectrum of alternatives, overlaps, fade-outs, palimpsest occasions, and rebel silhouettes” (105, 111). He proposes: “Islam is often the metoikos, the Stranger in the House of Asia interpreted as a curatorial conception—the person of no fixed address, the haphazard member of the herd. Let us consider the claim that this metoikos makes on us” (107). Hoskote concludes with a rhetorical question: “Can we model our conceptual curation of the House of Islam in the manner of al-Andalus, as a near-utopian ecumene of engaged divergences?” (111). Thus, this critic explores the past as a model for the future.

Problems of religion and secularism in the present animate Adajania’s essay on sacrality, spirituality, and ritual in the work of three contemporary Indian artists: Shilpa Gupta, Jehangir Jani, and Vidya Kamat. By her account, these artists “use their religious and ethnic legacies as cultural materials, pointers toward the investigation of a selfhood that is embedded in family, group, and lineage—a territory that is anterior to, though imbricated in, the more generalizing norms of citizenship” (117–18). In so doing, they challenge both a secular Left consensus in the art world and the political culture of Hindu majoritarianism in India, and claim a position for the artist as “insider/outsider or participant/witness . . . so that empathy and analysis, detachment and concern, become quick-changing conditions of encounter rather than fixed and distinct parameters of approach” (118). Such positions were foreclosed or marginalized by modernist practice in India; their appearance in the contemporary art world can be viewed as a rejection or rethinking of modernism.

S. Santosh extends Adajania’s critique of modernism in India, which he views as the cultural practices of an “upper-caste national bourgeois[ie] in the name of national identity, authenticity, and sovereignty” (200). For Santosh, the case of Ramkinkar Baij (1906–1980), a modernist sculptor and painter based in Bengal, exemplifies the biases and exclusions of a hegemonic national art history. Citing Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s theory of minor literature, he identifies a minor impulse in the works of the contemporary Indian artists Savi Sawarkar and Zakkir Hussain, inheritors of Baij’s radical project to represent subaltern consciousness. Santosh redefines Dalit (literally, broken or crushed; the contemporary political identity claimed by people classified as untouchables under the Hindu caste system) as an aesthetic and a community that can “break away from statist, anthropological, and religious categories of caste, tribe, and class.” Dalit aesthetics offer a “counter-institutional mode of production” (210). According to Santosh, a “minoritarian” and “anti-essentialist” notion of Dalit can resignify “caste as an analytical category” that yields “possibilities of decentering, differentiation, relationality, liminality, sharing, and linkage” (210). Thus, contemporary art provides a space for the emergence of new forms of social and political subjectivity. This emergence is the subject of Y. S. Alone’s essay on Sawarkar’s iconography, which highlights the coarticulation of caste and gender difference. Alone views the artist’s paintings of Dalit women, specifically of devadasis (women who, as children, are given by their parents to the temple and dedicated to the goddess), as “translating marks of caste into pictorial codes,” a gesture that distinguishes Sawarkar’s practice of art (215).

The absence of critical voices from mainland China and the lack of an extended discussion of the phenomenon of contemporary Chinese art is perhaps the greatest strength and weakness of the volume. InFlux provides a different regional perspective than many popular and scholarly accounts of contemporary Asian art that focus on China to the exclusion of practices and discourses elsewhere. In the twenty-first century, the Chinese art market has emerged as the second largest in the world after that of the United States.7 In Asia, China is an old and new force to be reckoned with. The contributors to InFlux are uniquely positioned to offer new insights into the global influence of Chinese art, yet the volume does not take up this opportunity. This omission may be related to the location of the original conference and the editors in New Delhi, which has had a troubled relationship with Beijing since the Sino-Indian War in 1962. Cultural exchange between the two Asian nations is low, and barriers to trade have been high in the past. InFlux reflects these social and historical conditions and brings other trade routes and geographies into focus: those that connect South Asia and Southeast Asia to Central Asia and West Asia.

Richly illustrated and compellingly argued, InFlux will be of interest to scholars of modern and contemporary art, museum studies, Asian studies, and cultural studies. It is a welcome addition to our knowledge of the globalizing art world and a critical step toward reimagining Asia and contemporary art.

Sonal Khullar is an associate professor of South Asian art history at the University of Washington. She is the author of Worldly Affiliations: Artistic Practice, National Identity, and Modernism in India, 1930–1990 (University of California Press, 2015). Her current research focuses on conflict, collaboration, and globalization in South Asia.

- See Gulammohammed Sheikh, “The World of Jangarh Singh Shyam,” in Other Masters: Five Contemporary Folk and Tribal Artists of India, ed. Jyotindra Jain (New Delhi: Crafts Museum and the Handicrafts and Handlooms Exports Corporation of India, 1998), 17–34. ↩

- See Gayatri Sinha, “Indian Artist Commits Suicide in Japan,” The Hindu, July 7, 2001, at www.thehindu.com/2001/07/07/stories/02070003.htm, as of January 12, 2015. ↩

- “Mithila Museum, An Introduction,” at www.mithila-museum.com/aboutMM/Eindex.html, as of January 12, 2015. ↩

- Nisha Susan, “Jangarh Singh Shyam Committed Suicide Nine Years Ago. Now, as His Clan Pushes His Legacy, Gond Art Is Becoming a Rage Abroad,” Tehelka, July 31, 2010, at www.tehelka.com/jangarh-shyam-committed-suicide-nine-years-ago-now-as-his-clan-pushes-his-legacy-gond-art-is-becoming-a-rage-abroad/, as of January 12, 2015. ↩

- See for example, Terry Smith, “The Postcolonial Turn,” in What Is Contemporary Art? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 151–71. ↩

- Geeta Kapur, In Quest of Identity: Art and Indigenism in Post-Colonial Culture with Special Reference to Contemporary Indian Painting (Baroda, India: Vrishchik, 1973). This essay, submitted as a master’s thesis at the Royal College of Art, London, in 1970, was serialized in the journal Vrishchik in 1971 and 1972, and published in its entirety as a special publication in 1973. ↩

- “Christie’s v the People’s Army,” Economist, September 28, 2013, at www.economist.com/news/business/21586881-foreign-auctioneers-have-begun-enter-chinas-huge-unruly-art-market-they-will-not-find-it/, as of August 17, 2015. ↩