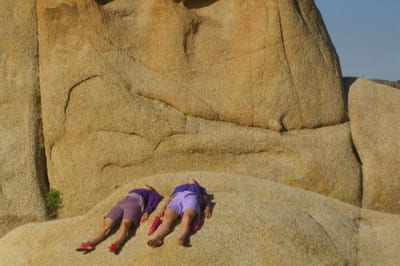

robbinschilds, still from C.L.U.E (color location ultimate experience), Part I, 2007, digital video projection, color, and sound, 10 min., 48 sec. (artwork © robbinschilds; video still © robbinschilds and A. L. Steiner)

In 2003, Sonya Robbins and Layla Childs formed robbinschilds, their eponymous dance and choreography company, and have since steadily performed in settings such as deserts, forests, mossy landscapes, a geodesic dome, and long and narrow museum staircases. Like many post-postmodern dancers, their training and thinking about dance stems from the Judson Dance Theater’s philosophy of commonplace movement and gesture as the stuff of art. But robbinschilds has developed a signature attachment to sites that has made their work especially germane to contemporary visual art and exhibition spaces. Setting and site operate as intrinsic elements and characters in robbinschilds’s choreography, which is what prompted me to invite them in 2010 to create a building-specific work for Temporary Structures: Performing Architecture in Contemporary Art (September 18–December 31, 2011) at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum. The show delved into the overlap of performing bodies and architectural imagery, from Gordon Matta-Clark and Ant Farm to Sarah Oppenheimer, Mary Ellen Carroll, and robbinschilds, among others. The concept of the exhibition was rooted in highlighting the vulnerability of architecture, bringing it in alliance with the human body as a mobile, temporary, and even soft entity (yes—there was an inflatable, by Alex Schweder, and it even glowed in the dark). I approached Sonya and Layla after seeing C.L.U.E (color location ultimate experience) (2007), both a video with A. L. Steiner and a live performance at the New Museum, in which they slunk down the first of the many long, narrow staircases mentioned above. I was struck by the way their choreography rubbed against the building, literally and metaphorically, and changed our perception of it. And so they drove up to the rolling hills of Massachusetts to a converted castle-home on the hills that is the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum—itself an architectural guessing game.

A former private home, the deCordova’s building and landscape was gifted to the town of Lincoln in 1930 by a local collector, Julian de Cordova. De Cordova donated his estate as an arts center with the intention that it be made public following his death. Inspired by his European travels, de Cordova converted his 19th-century summer home into an eccentric, Moorish-style castle in 1910, replete with brick turrets and stonework archways. After de Cordova’s death in 1945, Walter Gropius, his neighbor and the director of the Harvard Graduate School of design, transformed the property in a museum with streamlined, geometric forms, white-walled galleries, and glass and metal entrances. In the late 1990s a three-story addition was created in full postmodern regalia. It included a huge, almost functionless central window feature that faces a narrow hallway, and looks out onto the grounds. At 35 acres, the grounds define the museum as a sculpture park and center for contemporary sculpture. The building rambles through architectural history and modalities, which shifts from public to domestic scales at a rapid pace that can be confusing for first-time visitors.

In the interview below, Sonya, Layla, and I discuss their commission, Constructions I–IV, a group of movement pieces devised for a series of the museum’s gallery spaces during nonpublic periods, and displayed as video in each space during the exhibition. Layla and Sonya act as dancers and choreographers, and derive their actions from the properties of the various spaces: an empty gallery (the Edward and Joyce Linde Gallery), a library, and a small window alcove (dubbed the Olive Room by the artists). The fourth and final portion of the piece, set in the Olive Room, was an interactive portion in which visitors performed a series of audio and visual instructions presented by the artists, enacting robbinschilds’s own system of responsive movement.

-Dina Deitsch

robbinschilds, Construction III: Library, 2011, multi-channel digital video installation, runtime varies (artwork © robbinschilds)

Deitsch: Let’s begin with your project for Temporary Structures. Based on your previous work, you conceived of a new, site-respondent project for the museum building, a site that is a little quirky and unconventional, as it is an expanded home, castle, and museum. The deCordova’s space has always been a bit convoluted, but set in the loveliness of Boston’s “countryside.” Can you describe how you approached this project or, rather, problem?

Robbins: When we did our first site visit of the deCordova, we were definitely struck by the multiple “personalities” contained within the building, and the way the museum is positioned within the landscape around it. It felt like the museum was growing out of the hillside especially when entering as we did, from its base. It’s funny to reflect on this so long after the fact, because at the time we were mainly eager to focus on the concrete details of the place. Now, a few years, later it’s easier to click into the sensorial experience of that first viewing. I remember clearly the heat of the day, a muggy late July scorcher, and as enticing as the grounds were, I mainly wanted to retreat into the coolness and quietude of the building. From the beginning we knew we wanted to work inside the space, in spite of the lovely exterior.

I agree with your description of the building as being a bit convoluted, but for us there was an attraction to that hodge-podge quality. robbinschilds has a long interest in ideas around topography, whether it is naturally occurring via geology, or represented in layers of use and purpose within built environments. Having an unconventional building to use as source material for our piece was a boon in our eyes. The locations we chose to respond to were each distinct in their energetic qualities and their intended purpose. The library felt like the most historic and un-temporary of the sites, the large gallery (Edward and Joyce Linde Gallery) represented a contemporary art frame, and the small space at the end of the fourth floor hallway (the Olive Room) was an interesting transitory spot bridging indoors with outdoors because of its location and large picture window.

As is often the case in our process, we had many other initial ideas of places we wanted to work within the museum—we kept trying to think of a way to engage with the stairwell, to no avail—but in the end, when we were actually scoring and filming material, we found that the three spots we selected generated a tremendous amount of material. We timed our shoot to when the museum was between shows, which meant that the Linde space was being reorganized to accommodate a new exhibition. We had planned this primarily so that we could film without worrying about photographing the public or another artist’s work, but what ended up happening is that each day we were there, the gallery space looked different. Walls were stripped down to studs, they were sometimes laid flat on the floor, and another evening they had been rotated 90 degrees which bisected the space. In hindsight this seems so obvious: the gallery is a perfect expression of a temporary structure, duh! But in truth we had thought we were going to go in and improvise and perform within a white, neutral space—one that had certainly achieved a “fixed” quality in our imaginings preshoot—so it was a happy surprise to instead work with a dynamic and morphing space.

robbinschilds, Construction I: Linde, 2011, two-channel digital video, 4 min., 49 sec. (artwork © robbinschilds)

Childs: Exactly. In a sense we found a way to engage with the very impermanence of the gallery and perhaps even all the residue of what had come before in the space, with both the art and the walls ever in transition. Typically, when a viewer enters an installed exhibit, the perception is that the space is somehow neutral or fixed, as if that is what the space always looks like. Our video performance attunes an awareness of the gallery space as transient and thus (hopefully) highlights our human relationships with the spaces we inhabit.

I recall when we first visited, Martha Friedman’s exhibition Rubbers was installed and the small, fourth-floor gallery contained a large rubber pimento olive sculpture (Pucker, 2010). From then on, we referred to that space as the Olive Room and the videos made in it kept that reference imbedded in the titles. It’s sort of funny how it stuck.

Martha Friedman, Pucker, 2010, rubber and wood, 3 ft. x 8 in. x 7 in. (91.44 x 20.32 x 17.78 cm) (artwork © Martha Friedman; photograph by James Ewing, provided by the artist and Wallspace, New York)

Deitsch: I’m impressed that years later, you are both able to bring up the physical experience of the building. As dancers, it’s safe to say that you’re well-trained in the postmodern ethos of Lucinda Childs and Yvonne Rainer, in which everyday gestures operate as a dance vocabulary. Your work has gone further by incorporating space into this same language. How do setting and place play into your choreographic thinking?

Childs: Looking back, our early dance works were also quite influenced by the Merce Cunningham-style of movement and environment, as well steeped in the postmodern ethos you allude to. While at Bard College, we both studied with Albert Reid, a former Cunningham company member. We developed an affinity for his work, and continued to see old and new pieces of his performed throughout the early 2000s. At some point early on in our collaborative process, we came up with the term “extra-pedestrian” to describe our movement aesthetic and sensibility. This is both a wink to the postmodern use of pedestrian or everyday as you mentioned, and a playful allusion to extraterrestrial life-forms. Our interest from the beginning of our partnership has so often been in responding to architecture or place by a process of turning on a heightened state of awareness—this amplification is the “extra.”

What began initially as choreographing dances within installed stage environments evolved into to site-reactive works in found locations. In 2005 we stepped out of our studio practice to shoot a video piece C.L.U.E. (color location ultimate experience) out in the California desert and a variety of other natural and human-made sites. We created choreography in the studio that drew from our contemporary, postmodern dance training. We took that lexicon out of the dance studio environs and on the road. This shift allowed the terrain to inform how the choreography would be expressed. The new process was very liberating, and since then we have created works in many diverse locations. The series we created at deCordova came out of this longtime practice of discovery and adaptation to place. While our work certainly stems from our training in contemporary dance, the movement languages we create do not lean on formal technique but are deeply informed by the sensibility and internal logic of contemporary dance forms.

We do still make work for the theater and enjoy this equally as much as our work in the field. Now it seems that we bridge back and forth between these worlds, outside and in. Our relationship as longtime collaborators is in itself a site that we often draw from.

robbinschilds, Construction IV: Olive Room, 2011, two-channel digital video and audio installation, 15 min. (artwork © robbinschilds)

Robbins: Also, when we work outside of a theater frame—within a more “pedestrian” landscape—there is the added element of spontaneous drama that can erupt from unexpected sources. In the example of C.L.U.E. mentioned above, Layla is highlighting how we were constantly grappling with uneven surfaces, weather, and more. The choreography was in constant dialogue with the topography, and part of the drama (comedic and otherwise) of that piece is watching the two of us work with, around, or against the characteristics of the settings. In a way our version of pedestrian, our extra-pedestrian, is infused with some remnants of theatrical approach: it’s performative, heightened, sometimes silly. I think the Judson school was utilizing pedestrian activity to turn away from spectacle or theatrics. I’m thinking of Yvonne Rainer’s famous “No Manifesto.” Although we are deeply imprinted by Judson-era aesthetics and ideas, robbinschilds embraces camp, magic, transformation, and humor.

robbinschilds, Construction IV: Olive Room, 2011, two-channel digital video and audio installation, 15 min. (artwork © robbinschilds)

Deitsch: It’s helpful to think about the field in which you work as both physical—as in the site or place—and conceptual in your collaboration, in which both are structures in which you negotiate and respond. As you begin each project, what sets off this process of negotiation? Where does one begin: with the chicken or the egg?

Childs: The chicken or the egg is a really good question. After working together for so many years, there’s an unspoken thing that happens where we kind of intuit our way into a project. It’s not that we don’t do a lot of talking—we certainly do—but there’s a trust that we are seeing and envisioning something similar enough that we are propelled forward. Sometimes we make very clear choices from the start, and in other moments we allow room for improvisation and indeterminacy. In planning the Constructions, we had chosen sites based on spaces that sparked us. Our collaborative energy often includes a lot of humor or personality, so our explorations can sometimes express a playfulness.

The Linde piece was the most open-ended of the works, since we weren’t sure what the gallery would look like until we arrived to shoot. In this case, we were working with improvisational duets using the space as a found-site with all of the elements present: ladders, drop clothes, dollies, debris, and so forth. The library had this great modular table and chairs which became a way to dissemble the architecture of room and construct a series of living sculptures in the space. For the Olive Room pieces, we followed a more organized format in which we set out to design an experiential possibility for the gallery visitor, who can watch us perform on screen and then enact those very gestures in the same physical space. There is a simultaneous responding to the architecture or locality as well as to one another, a layering of relationships.

robbinschilds, still from C.L.U.E (color location ultimate experience), Part I, 2007, digital video projection, color, and sound, 10 min., 48 sec. (artwork © robbinschilds; video still © robbinschilds and A. L. Steiner)

Robbins: I think it took a few years of working together before we became actively conscious of our collaboration as a structure or concept of its own. Because Layla and I have a personal history that precedes robbinschilds, as friends and also as performers in one another’s work, we began working together in an organic and informal way. We initially joined forces out of a shared aesthetic interest, a desire to address site or locale directly within a theater-based work. In the early days, robbinschilds was more oriented toward place, and conversations around the interface between person and site dominated our creative dialogue.

After a few projects, though, that dialogue started to push forward and become the focus of the work itself, and we made a few pieces where the collaborative structure was both the subject and the generative mechanism of our work (Sonya and Layla Go Camping from 2009 was our magnum opus on this topic).

Now ideas around shared authorship consciously inform every project we create, even though this may fluctuate in legibility for the viewer. The deCordova commission is an interesting example: since we made a series of works for the show, some of the Constructions illustrate more overt displays of collaborative making while other videos emphasize exploration of site.

Deitsch: Pushing this notion of collaboration and shared authorship further, how do you frame the ultimate collaboration with your audience? As you shift sites and means of presenting your work—from live to recorded, from stage to landscape to gallery—the connection to the viewer changes radically, echoing many of the issues Yvonne Rainer and her contemporaries contended with through anti-spectacle strategies in the burgeoning media culture of 1960s 1. In Constructions, there’s a distinct play between the screen and interactive performances. The majority of the installations were presented on monitors in situ with the exception of the fourth floor Olive Room installation, which, in part, functions as a culmination of the project, where you created a space for the audience to participate.

robbinschilds, C.L.U.E (color location ultimate experience), 2008, live performance at New Museum, New York (artwork © robbinschilds; photograph © Kevin Dohn)

Robbins: The series of works we made for Temporary Structures offer a wide array of entry points for the viewer. Some of the pieces (Linde and the Library constructions) are intended to be experienced by watching the piece as a video work. Those works were performed in real time for the camera and subsequently rechoreographed through the editing process. From the early stages of conceptualization, the audience’s eyes take the form of the spectator in these works.

In juxtaposition to this is Olive Room, which was constructed to engage viewers from a different angle. Layla and I wanted to create a participatory strand for our deCordova commission, with the desire to create opportunities for museum audiences to take a more dynamic position in their experience of the show. For this Construction we began with an initial idea of performing for each other. To go back further, we actually began by writing and recording directive scores for each other, which only complicates the notions of performer and audience. Those early audio score tracks were the first private performance of the work.

Olive Room shows a single body performing for the camera and subsequently, the gallery visitor. Because of the audio component that is broadcast into the space, viewers are directly invited into the experience of the moving body they see on the screen. We intentionally did not plan for the sound to line up exactly with the actions seen in the video, though there were likely times in the day when that might have happened. What we hoped to underscore was that the piece offered layers of witnessing: from the lens of the camera to the passive viewer watching the monitor, to an activated visitor who spontaneously tries out one of the broadcast directives, to the passerby who is watching the visitor’s impromptu physical exploration. This topographical approach to bearing witness is not present in all of robbinschilds’s work, so I’m trying to highlight the distinction through this example.

Deitsch: This engagement with the viewer and gallery architecture defines you among a number of dancers who have successfully collaborated and crossed over into the museum setting—in these site respondent installations like the one at deCordova and C.L.U.E., which has been shown widely as a video and performance. Over the past decade, museums and art institutions have rushed to commission, exhibit, and preserve performance and dance—for instance Trisha Brown’s 2008 retrospective at the Walker Arts Center and the Tate’s hosting of the Musée de la Danse for two days in May, 2015—but it’s taken a while. From the dance point of view, how do you perceive this surge in the art world?

Childs: It certainly does seem that dance has become somewhat of a hot commodity in the art world. This is a tough one to pin down. It does sometimes feel that there is a novelty cachet around programming dance and performance within the museum and art institution setting. Some of these partnerships are more successful than others. The museum may not always understand the dynamics of live, time-based works that were not originally conceived for such spaces. Dealing with living, breathing human beings and their particular needs is a big responsibility and undertaking. The kind of viewership or audience interaction in such settings holds a different expectation than in a theater, or a space where people have come only to see that work, and are not fitting it into their museum visit.

A great example of what I consider to be a very successful presentation of a choreographer’s work in a museum was the recent Retrospective by Xavier LeRoy at MoMA PS1 (October 2–December 1, 2014). For starters, the exhibition was two months long, which gave the work ample time to settle into its environs. LeRoy worked with a team of performers who fused together pieces of LeRoy’s past choreographies with their own histories and choreographies to create a rich and dynamic pastiche of material (dance and text) cycling throughout a large gallery room as audience members came and went on their own rhythms. As each new viewer entered the space, a kind of resetting would occur which was a satisfying element of reactivity.

LeRoy opted to work with this gallery setting to create an original site-responsive piece instead of trying to fit a square peg in a round hole. I don’t know the working dynamics of the relationship between the museum and the choreographer, but as an audience member, I was very satisfied by the work and wanted to see it more than once. Incidentally, Sonya’s partner was in the work.

robbinschilds, still from C.L.U.E (color location ultimate experience), Part I, 2007, digital video projection, color, and sound, 10 min., 48 sec. (artwork © robbinschilds; video still © robbinschilds and A. L. Steiner)

Robbins: He was in it, and had a wholly positive experience doing the piece, which I think speaks to the strength of LeRoy’s approach. Often the manner in which large museums program performance into their buildings is fundamentally disempowering for the artist. Aside from the primary budgetary issue, which W.A.G.E. is doing such good activist work on, there are also countless logistical needs that come into play related to the presentation of live art that are not pressing within other mediums. I like that Layla is highlighting the humanity of our form. These are actual breathing, living bodies enacting this work. I found the structure of the LeRoy retrospective oriented toward enhancing the performers’ agency, rather than objectifying them. The museum viewer was continually reminded of the dancers’ humanity, of their histories and evolutions within their relationship to dance. What an incredible and dismantling version of the concept of retrospective!

As to why visual art institutions are so keen to showcase performance and dance, I’m not sure we’re going to nail that down in a succinct, tidy answer. I’m reticent to even attempt a summation! I don’t want to frame it only as faddish or superficial, a passing interest. We have definitely had very fulfilling and respectful experiences with curators who welcomed the particular challenges presenting live art in museum settings. In those cases, we felt that our form was trusted by the curator and that there wasn’t a need it to be entertaining or digestible as “dance” to the museum attendees. This seems so obvious, but based on our experiences it has not always been the norm. The larger systemic hurdles that can impinge on presentation relate to a consumer- or market-driven approach to curating. I’m sure visual artists struggle with this issue as well. A primary and fundamental difference is that dance doesn’t produce that tangible commodity, a piece of art that can be held, valued, and sold. In that sense, we’re outliers in a market-driven art world. Which is maybe kind of sexy, different, and sort of exotic for a curator?

Deitsch: I do think many museum curators feel an obligation to show work that lies outside the market as an imperative of their nonprofit status, as a way to create and ensure a public space and dialogue for such work. To your point, even these spaces cannot and do not operate outside market forces. Within this context where, if any, is the line between dance and performance? The two disciplines have separate histories but, especially recently, seem to merge in these programmatic spaces.

Robbins: I don’t think either Layla or I see a hard line between dance and performance; it’s more of a spectrum for us. Our work has always incorporated a moving body, and in some of our works movement has appeared more recognizably as dance whereas other works steer harder into a performance zone. I suppose if I had to qualify the ends of the spectrum or continuum, I’d think about the process of how the piece was made and the context in which it was viewed. robbinschilds’s more dance-oriented works typically involve periods of time working in a dance rehearsal studio, often with other performers. They include set choreography, and we would rehearse the material over the course of many months in preparation for a show. That show would then be repeated, more or less, for the course of the run, and would involve an audience coming for the beginning, middle, and end.

Our works that feel less dance-oriented often take place outside a theater environs—in a gallery or museum for example. They employ improvisational structures, site-reactive states, and as a result they wouldn’t be as codified or available for replication the way our dance works might be. We also wouldn’t expect viewers to necessarily engage throughout the entire arc of the performance.

Defining these ends of a spectrum feels completely personal, meaning that what robbinschilds sees more as performance and less as dance could be at odds with another maker’s sensibilities. I’ve steered clear of commenting on or categorizing other people’s work for that reason.

robbinschilds, I Came Here on My Own, 2012, four-channel digital video installation, 34 min. (artwork © robbinschilds)

Childs: In our own creative circles, there is much dialogue around what dance is or what to call the work that is being made: movement-based work, dance, contemporary dance, experimental dance, and performance are a few examples. Often I think we try on different descriptors, and the naming of these genres is possibly always in transition. I’d say this kind of language is shifting in response to the field itself. Now if only we could get the reviewers to see how these new forms are evolving. For us, as Sonya has pointed out, we have a range of approaches, but there is always a relationship to the body, time, space. Even in the creation of our video pieces, the editing becomes a kind of choreography or arrangement of moving parts whether or not the end result appears to the viewer as dance.

Deitsch: Perhaps the last bastion of these lines is in media rather than in practice. We’ve talked about your work as collaborations with the two of you, with spaces, philosophies, but we’ve danced (pun intended) a bit around the subject of the curator, which is the underlying theme of this interview series. How has that relationship operated for you in the past?

Robbins: While we’ve had plenty of fruitful experiences with curators there have also been plenty of bumpy interactions too!

Childs: We have learned a great deal on the many adventures each new project has taken us on. On the invitation of a curator, we brought a piece to perform in Eastern Europe. We encountered a pretty extreme culture clash when we attempted to perform the piece in a public park. The performance had not been well-planned and our presence was received with much hostility and outrage. Bottle caps and banana peels were thrown at us. This was a blind spot on all of our parts to assume the meanings or conditions around public space usage in another country. While we don’t entirely hold the curator responsible, our interaction there was ill-conceived to say the least. Live and learn.

Deitsch: I can imagine that banana peels were not welcomed props. It all goes back to context, with the curator perhaps as a necessary mediator of said context or situation. After Constructions you made what I think is my all-time favorite video piece, I Came Here on My Own (2012), which follows you both on parallel screens through the landscapes of the Alps, Iceland, and the moss fields of New Zealand. Your characters are travelers, not unlike your figures in C.L.U.E. as you danced through the American landscape. But in this work, the two of you never connect. You tread the same dramatic landscapes as if following one another. I can’t help but see this as a wonderful metaphor for a partnership: similar but separate. Is that your survival technique?

robbinschilds, I Came Here on My Own, 2012, four-channel digital video installation, 34 min. (artwork © robbinschilds)

Robbins: Ha! Fighting for survival is right! It feels like a wilderness, this financially barren landscape of performance making. Yes, I Came Here on My Own—or ICHOMO, our faux German acronym—illustrates themes we’ve discovered over the course of a long-time shared process. The piece, a diptych, displays the parallel process of an epic quest (aka working through a project) alongside one another.

Childs: At the heart of this piece, we were interested in portraying a subtle kind of intimacy that comes from sharing experience while also having, even celebrating, one’s own separate experiences. This relates directly to our long-term collaboration, but touches on aspects of any partnership or closeness.

The division or ether between our separate but simultaneous journeys, projected as two discrete projections, at times seems to evaporate when the viewer perceives the mirroring as one complete panorama. Though it’s true we don’t directly interact or coexist on one screen, this is suggestive of those near-same moments we share with others along the proverbial path, be they in the same time continuum or not.

robbinschilds, I Came Here on My Own, 2012, four-channel digital video installation, 34 min. (artwork © robbinschilds)

Robbins: The name of our company robbinschilds is even a bit of a misnomer since we’re not interested in actually fusing our identities together. There’s a Layla and a Sonya, and we aren’t trying to share a brain or a singular vision.

I don’t think we really got that in the formation of our duo so many years ago; it has taken time to understand the intersubjectivity that we rely on to grow our ideas. For me the most fertile stage of robbinschilds’s practice takes place within our dialogue around ideas. When we are speaking about ideas, rather than doing or enacting them, there’s no way Layla and I are envisioning the same thing. So essentially yes, there is value in the space or separation between us because that is ultimately the site of the amorphous imaginative riffing or storytelling that is foundational to our work.

It is related to survival for other reasons as well. This field presents so many logistical structural challenges that it can overwhelm an individual, and wading through it as a team can open up a double can of worms. For example, there are two rents that need to be paid, and other major life responsibilities (we are both parents) that are tough to balance out with art-making. In spite of that, working as a partnership has functioned as a major source of support and morale. There is no more fearful, dramatic landscape to tread through than that of an uncomfortable meeting with a potential presenter. Having Layla alongside me is most certainly a survival technique in those moments!

Childs: For sure! While our creative dialogue and practice together is almost always fertile, to echo the cry of Grandmaster Flash on “The Message”: “It’s like a jungle sometimes, it makes me wonder how I keep from going under.” As for the two of us, we most definitely continue to buoy, nudge, and at times hoist each other along in our journey as genre-straddling artist partners. Waiter, I’ll have a martini dry with two olives and a giant grant on the side, please. Make that two!

Dina Deitsch is Director of Curatorial Projects for GoodmanTaft, where she oversees artist commissions and publications, and faculty at Massachusetts College of Art and Design and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. She was curator of contemporary art at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, Massachusetts, from 2008 to 2014, where she organized Temporary Structures among numerous other projects. She received her BA from Yeshiva University, MA from Williams College, and MPhil from the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU.

robbinschilds was formed by choreographers, Sonya Robbins and Layla Childs in 2003. Though trained in and rooted by a background in dance, robbinschilds often works outside of that discipline, engaging in site-specific and installation-based performances which contain elements of video, sound and sculpture. The duo creates performance and video works for diverse venues including the stage, gallery, museum or site. In their presentation of time-based work robbinschilds explores the juncture between architecture or place, and human interaction. robbinschilds’s live performances and video art have been presented at numerous venues, including The Kitchen (New York), Dance Theater Workshop (New York), MoMA PS1, Movement Research at Judson Church (New York), SFMOMA, The Art Center (Salina, KS), The Marfa Ballroom, The Donau Festival (Krems, Austria), Vaska Emanouilova Gallery Sofia (Bulgaria), Zendai MoMa Shanghai (China), New Museum, Reina Sofia Museum (Madrid), and Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave series. Recent company residencies include Mt. Tremper Arts in upstate New York, The Arts Center in Christchurch, New Zealand, and The LAB in Philadelphia PA.

- See Carrie Lambert-Beatty, Being Watched: Yvonne Rainer and the 1960s (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008) ↩