Kate Gilmore, gallery installation view of Like This, Before, 2013, video, wood, glass, paint (artwork © Kate Gilmore, image courtesy of Clements Photography and Design)

In 2013, Evan Garza (now assistant curator of modern and contemporary Art at the Blanton Museum of Art) and I cocurated the exhibition Paint Things: Beyond the Stretcher at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum (on view January 27–April 21, 2013). The exhibition was a sculptural look at contemporary, expanded painting practices. The show hinged on work from the 1990s by Jessica Stockholder and Cheryl Donegan—two artists who addressed painting and its history through irreverent uses of inexpensive, ready-made objects in the case of Stockholder, and semi-erotic, feminist-based performances in the case of Donegan. Starting with these two artists, the exhibition went on to highlight younger artists working in the twenty-first century who similarly and properly permeated painting with the conditions of sculpture: dimensional space and time. Kate Gilmore’s performance and paint-infused practice formed a key and central point in the exhibition. Ostensibly a video artist, Gilmore uses a fairly structured process in which she sets up a specific action for filming, and before a fixed camera with no audience she executes that action. Most often the tasks she assigns herself are futile, repetitive, and incredibly messy, involving paint or clay, and Gilmore consistently dresses in the impractical uniform of a dress or skirt and heels as overt indicators of her gender. The video ends once the performance is complete, and often the object remains as the aftermath in the gallery. In her approach to video, Gilmore sits squarely within the legacy set out by Bruce Nauman’s late-1960s studio-based works as well as the body-centric performances of the same era by Chris Burden, Barbara T. Smith, and Carolee Schneemann. Her work, though, is defined by a specific blend of self-deprecating humor, third-wave feminism, and a deep appreciation for materials.

Jessica Stockholder, Kissing the Wall #5 with Yellow, 1990, chair, oil and latex and acrylic paint, fluorescent light, paper, glue, 30 x 36 x 54 inches (artwork © Jessica Stockholder, photograph © Clements Photography and Design, Boston)

Cheryl Donegan, Head, 1993, video, 2 min., 49 sec. (artwork © Cheryl Donegan)

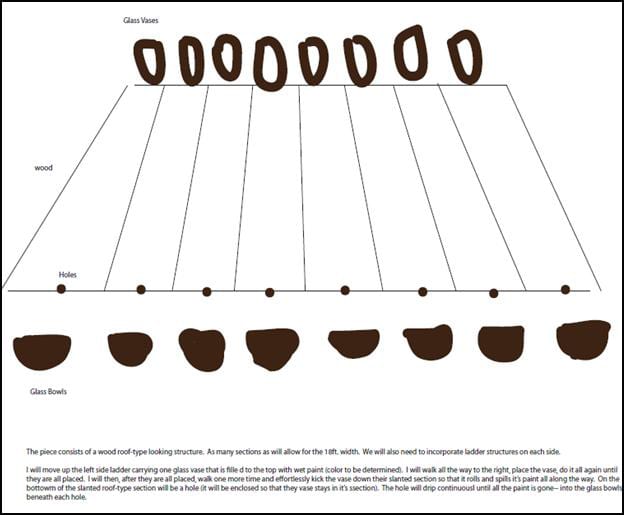

For Paint Things, Gilmore conceived and performed Like This, Before. The museum built a large, wooden tilted structure based on her sketches for the piece, and painted it a deep, flat black. The structure was eight feet tall at its highest point and ran fifteen feet across, just a bit larger than human scale to make it both manageable within the space and yet intimidating to climb. Fifteen large, glass vases were filled with white paint while fifteen empty, spherical vessels sat at the base of the channels. One evening, prior to the opening, Gilmore performed the work in an empty gallery, save for a valiant videographer (Michelle McNamara), in a single, stressful take. Over the course of fifteen minutes, she lugged each vase up the eight-foot ladder and placed it at the top of a channel on the walkway. The scene concluded with Gilmore gently tipping each vase with a red-high-heel-clad foot, which caused it to shatter and spill the paint down the sloped panel. The paint filled each receiving vessel and dried over the course of the exhibition.

Below Kate and I discuss the process of making this work and the importance of breaking things and laughing about it.

-Dina Deitsch

Kate Gilmore, Like This, Before, 2013, HD video, 13 min., 38 sec. (artwork © Kate Gilmore)

Dina Deitsch: In Like This, Before (2013) you set up a performative action and object that was very much about painting and its traditions. You keep things pretty restrained for the bulk of the work: the set and your outfit are in black and white (except for your red shoes), the staging is symmetrical, and your actions, quite typically, are slow and repetitive. It ends with the incredibly cathartic yet simple gesture of tipping over fifteen paint-filled glass vases. You give us action painting for the twenty-first century, but it’s rife with contradictions and contrasts: boredom and shock, black and white, and in the very shape of those vases—male and female. Where does the legacy of or discourse surrounding action painting fit into our contemporary lexicon of performance, video, and painting?

Kate Gilmore: Like This, Before, the piece that I made with you at the deCordova for Paint Things, was specifically made with “painting” in mind as the show was about making paintings without making paintings. I often think about our art “heroes”— how their myths are created, how their greatness is achieved, and, of course, the complicated social and political history behind their work. For Like This, Before, I decided to focus on Frank Stella’s black-and-white stripe paintings from the late 1950s. They are spectacular, beautiful, and filled with the gravitas of many male artists of that time. Look at the stripes! The white! The drama! While I do love those paintings, these ways of referring to his work reflects of the way we often speak about painting (heroic language), and it is most often spoken of in terms of male artists. In my piece, I wanted to speak to the beauty of Stella’s paintings while exploring the politics behind it. Through referencing the piece very specifically (black-and-white stripes) and, at the same moment, making fun of the drama of it through the laborious climbing and walking with the climax of the breaking at the end, I hoped to show an appreciation for the process of art-making, but also question those who are revered and those who go unremembered.

Deitsch: Is there anyone specifically unremembered for you within this history of heroic painting?

Kate Gilmore, still from Like This, Before, 2013, HD video, 13 min., 38 sec. (artwork © Kate Gilmore)

Gilmore: I think that those unremembered are unremembered because they are unknown. Of course there are those that do not have the success that they should (in my humble opinion), but I am interested in exploring why some people come to the surface and why others sink to the bottom. Usually this reflects our status in society, our class, gender, race, etc. This predicament exists in every aspect of our society, from politics to art. . .

Deitsch: Do you see yourself as a stand-in of sorts for the women who came before you? And as a working artist yourself, how do you avoid falling through those said cracks? Or is that just wrong to ask? 1

Gilmore: It’s terribly wrong to ask! I have no idea how to avoid falling between the cracks, how to not be forgotten, how to continue to be relevant. I do feel an obligation to my history—art and political—to carry a message forward, to provoke, to be unapologetic. I do feel it’s important to know what you come from, who came before you, who fought for what you have, our history. If we forget or dismiss that, we are left in a position to repeat a not-so-glorious past and continue to perpetuate inequality in every spectrum. But I can ask you the same question—a career is a career is a career, right?

Deitsch: Indeed. You make a good point that we tend to isolate or elevate the character of artists’ labor and the shaping of a career. Although artists do have a somewhat unique position within society, in that you can historicize yourself in the present in a way that, for example, a lawyer probably cannot. But as a curator I see my role as a mediator of sorts—flitting between the worlds of the studio and of the office and gallery—and therefore retaining characteristics of both. I too need to approach my work strategically: working on projects and with artists who I believe in, and who I believe will impact art-making going forward, while also handling a boss, office politics, and water-cooler gossip! That said, I think the answer is also similar—to create projects that are thoughtful of their own histories and milieu, but also simply to keep producing, just like any other career.

But back to your video—this reference, for me at least, is located in your practical/impractical red heels: a notable sartorial reminder, but also a hindrance for you as you climbed those stairs and lifted those vases. For the show you were kind enough to participate in a public conversation with Evan Garza, my cocurator for the show, and Franklin Evans, your colleague, friend, and fellow Paint Things artist, during which I remember them egging you on to use stilettos as your shoe choice. What did you make of that?

Kate Gilmore, still from Like This, Before, 2013, HD video, 13 min., 38 sec. (artwork © Kate Gilmore)

Gilmore: I’m in a flats stage right now. It seems more sensible. Stilettos are too sexed-out and don’t seem to serve a real function of productivity. I am interested in a shoe that looks good but can still carry out necessary tasks. I want the shoe to carry symbolic weight but not to overcome the entire democracy of the piece.

Deitsch: I can’t disagree with you there, and do appreciate your pragmatism, As you note, you become the “everywoman” in your videos—dressed to connote “female,” but nothing over the top or overly performative. Is this character/role part of what you see as missing in our art-historical and political narratives?

Gilmore: The way women are portrayed in art, politics, and media reflects certain female tropes but never seems to show how one functions in daily existence. We have the sexpot, the woman in charge, the dowdy old lady, the mother, the librarian, the model, the Rubenesque figure, etc. Perhaps we are all and none of these things in the same moment. We all poop—whether we choose stilettos or flats.

Deitsch: I never equated the bathroom with my shoes, but you make an excellent point about our footwear identity and the classic Madonna/whore complex (or the Jewish equivalent). A friend once pointed out to me that women artists never get the same allowance as men to simply be weird, to be the eccentric, to be the slightly mad tinkerer or wunderkid. Women artists, she noted (as an artist herself), are rarely seen as simply funny. In a new and perfect world, would you go there? I mean to the Borscht Belt?

Gilmore: I would love to go to the Borscht Belt, but I don’t think I have the skills for that. Being funny is a great compliment—it goes with intelligence. Humor is a brilliant way to bring people in, make them comfortable, and then you can turn the knife.

Kate Gilmore, still from Like This, Before, 2013, HD video, 13 min., 38 sec. (artwork © Kate Gilmore)

Deitsch: So humor becomes a lure or trap in a way to get at the hearty material?

Gilmore: Humor is definitely a trap in the same way that beauty or formalism is. How do we make people look, how do we make people invest?

Deitsch: As you create new projects, I know that a lot of them begin much in the way Like This, Before did, based on an invitation by a museum or organization. This is perhaps different from at the beginning of your career, when the projects began more so with your own questions. Can you describe your process a bit and how it changes based on the context?

Gilmore: My process usually begins with figuring out where something is going to take place. Often I am working with institutions to make work, which makes it more of a collaborative affair. I usually do a really crappy sketch (as you see here), followed by lots of phone calls, discussions with builders, curators, lawyers (waivers are needed if it’s dangerous), videographers, lighting people, editors, photographers, and performers if they are included. Through these conversations we decide what would be possible, how things can be made—what will work and what won’t. Then, I start getting into the nitty-gritty of things: research on materials that I will use, testing things to make sure they’ll do what I want them to do, clothing decisions, action choices, installation finalizations. I then go to the site, put on my clothes, and break stuff.

Deitsch: Breaking things is indeed a consistent thread in your work. Is the shatter your Brechtian shock moment or something else? In the deCordova piece, it’s an incredibly cathartic experience to watch and hear those vases shatter, and between the white paint and shape of the vases, a lot more, well, what can we say—orgasmic? But in all, I always found the shattering in Like This, Before really joyful and satisfying (although hearing it during the filming in the galleries was a bit more terrifying). In this it reminds me of Pipilotti Rist shattering car windows in Ever Is All Over (1997), itself a reference to the Dionysian Maenads and the reclamation of female power along with, of course, the importance of the bacchanalian impulse.

Gilmore: I love that Pipliotti Rist piece! How vibrant the colors are, how girly she is, how whimsical, holding this seemingly precious flower, then boom. By using the unexpected to “shatter” or “destroy,” Rist is challenging the preconceived notion of the female body being helpless and passive. She is using this strong female aesthetic to be powerful. I definitely relate to that in my work. Through breaking things, I am trying to go against what is expected of this character in order to make something beautiful and, of course, referential.

Deitsch: Have you noticed a shift in the depiction of women over the course of your career thus far? Sadly, I can’t help paralleling riot grrls to Gamergate. . .

Gilmore: I have noticed that there is a new comfortableness about using the word feminism. I remember how that word was the kiss of death for female artists—people didn’t want to be seen in that context. It’s refreshing for me to see it being embraced and explored by a younger generation of artists. A few notable examples include Amber Hawk Swanson, Kenya (Robinson), and Samantha Harmon. In terms of the depiction of women, I do think it changes from moment to moment. We will always have the stereotypical female representation as interpreted through the lens of male desire; I haven’t seen that develop in a complex way. However, I do think more women artists are portraying themselves or other women, and that is always great to see.

Deitsch: Do you see this character that you play/present as a female hero or the female version of the antihero? I’m thinking of male artists playing the antihero in the vein of Martin Kippenberger in his bloated self-portraits.

Gilmore: I see this character as the hero and antihero. She is a “super-type” character, yet flawed, clumsy, and not all-the-way together. She’s complex like all of us. She’s real.

Dina Deitsch is Director of Curatorial Projects for GoodmanTaft, where she oversees artist commissions and publications, and faculty at Massachusetts College of Art and Design and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. She was curator of contemporary art at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, Massachusetts, from 2008 to 2014, where she organized Paint Things among numerous other projects. She received her BA from Yeshiva University, MA from Williams College, and MPhil from the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU.

Kate Gilmore imposes upon her own physicality in post-feminist critiques of sex and gender. Gilmore shapes an aggregate of performance, video, sculpture, and photography with self-imposed restrictions and challenging objectives that recall the absurdity of Dadaism, the hyperbole of political cartoons, and the rigidity of political correctness. Gilmore was born in Washington DC, and lives and works in New York, NY. Recent exhibitions include: Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT; Fourth Moscow Biennale of Contemporary; Whitney Biennial; Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland; Brooklyn Museum; and Greater New York: 5 Year Review, PS1/MoMA Queens, NY; among others. Her work has been included in national and international exhibitions at venues including the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA; RISD Museum of Art, Providence; and MAK Museum of Art, Vienna, Austria. The artist’s work is in the permanent collections of Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art; Brooklyn Museum; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Centro Sperimentale per le Arti Contemporanee, Italy. She is represented by David Castillo Gallery in Miami.- For further discussion regarding female artists and artistic models, see “The Conversation: The Young Female Artist as Historian,” Catherine Wagley, at http://x-traonline.org/article/the-conversation-the-young-female-artist-as-historian ↩