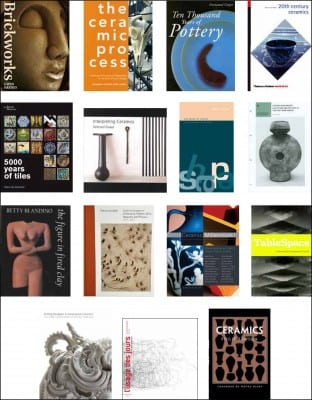

This introductory selection of texts on ceramics includes books that offer general foundations as well as essays that exemplify specific investigations. Although more extensive bibliographies of ceramics exist, which cover particular areas of what has always been a globally interconnected field, my selection represents what I would share with students in courses devoted to making ceramics.

Glenn Adamson, “Implications: The Modern Pot,” in Garth Clark et al., Shifting Paradigms in Contemporary Ceramics: The Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio Collection (New Haven: Yale University Press and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2012).

Adamson reexamines, if only in a brief essay, some of Philip Rawson’s ideas (see Rawson entry below) through the lenses of a collection amassed by Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio, their writings, as well as an “unexpectedly broad-minded” 1979 lecture on ceramics by Clement Greenberg. Form is about more than formalism because it is active in “the broader sphere of human needs,” as Clark wrote about a Betty Woodman cup.

Guillaume Bardet et al., L’Usage des jours: 365 objets en céramique (Suresnes: Bernard Chauveau, 2012).

Bardet made a drawing and its model each day for a year. With essays in French translated into English, this fully illustrated catalogue documents the collaboration between Bardet, twelve ceramists of Dieulefit, France, and the Manufactory of Sèvres, whose collaborative rendition of each of the drawings in ceramic during the following year won the Liliane Bettancourt Prize. More than a “use of days” for Bardet, these two years were a “wearing of days.” Though artists’ calendric mapping has become a familiar motif, for this project Bardet took up ceramics for its root in recording the passage of time and the memorialization of death. Through bowls, lamps, vases, stools, dildos, and still lifes, as well as folds, tubes, cuts (after the “cut-up” of Brion Gysin), and more, Bardet sought to exhaust his limits, to play fully within his chosen constraints.

For a video about Bardet’s project, including interviews with the designer and two collaborating ceramists, as well as workbench footage, see http://fr.loccitane.com/fp/ceramique-et-design-a-dieulefit,74,1,a1086.htm, as of November 25, 2014.

Betty Blandino, The Figure in Fired Clay (Woodstock, NY: Overlook, 2002).

Blandino writes that a fuller understanding of the figure in ceramic, beyond its written history, is gained through handling the raw materials and the finished objects. So much of the work on the figure is expressed as figurines made to be handled, yet Blandino resists the simplification of the female figure in countless iterations across the globe and across millennia to a “fertility” figure. Blandino acknowledges that her slim volume cannot account for even the best-known figurative traditions, though she offers analyses of examples that inspired contemporary artists like Richard Slee, Deidre McLaughlin, and others. Probably as a result of her own career as a potter, Blandino treats the figure more extensively in the form, the surface, or the concept of vessels.

Emmanuel Cooper, Ten Thousand Years of Pottery, 4th ed. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2000).

Cooper’s survey is one of the most recent and inclusive, with small sections on Native America and the global south. He adheres to a chronological description of technology and form bounded by nation-states. He gives more space to his native Britain, including the birth of glazed sanitaryware and a chapter on the Arts and Crafts movement. A chapter on studio ceramics features contemporary artists like Bodil Manz, Babs Haanen, and Judy Chicago, as well as the British artists Grayson Perry and Kate Malone.

Catherine Craft, “Isamu Noguchi: A Kind of Antisculpture,” in Return to Earth: Ceramic Sculpture of Fontana, Melotti, Miró, Noguchi, and Picasso 1943–1963, ed. Jed Morse, exh. cat. (Dallas: Nasher Sculpture Center, 2013).

Noguchi spent his life negotiating his biracial heritage, further polarized by World War II. Formless clay and empty ceramics suited the overflow of the one into the other. Noguchi disrupted Japanese categories of ceramics, combining materials that had been kept separate, at the moment of the emergence of Japanese avant-garde artists such as Yagi Kazuo. Though attracted to the “primal matter,” Noguchi remained ambivalent toward it. “You can make clay look like anything—that’s the danger,” he said.

Edmund de Waal, 20th Century Ceramics (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003).

De Waal’s short book is the most comprehensive survey of recent European, North American, and East Asian ceramics. In four chapters dividing the century, de Waal moves through these regions tracing such themes as collaborative and solitary authorship, display and use, insiders and outsiders working in ceramics, and the paths to meaning determined by seeing, handling, or entering ceramics. He also considers “abdication of skill [and] theatrical demonstration of skill,” the role of ceramics in early abstraction, and the reclamation of decoration in the 1970s. In conclusion, “the period of sensitivity to national allusion and quotation may be a phase in the history of twentieth-century ceramics that is coming to a close.” However, “it is more difficult than ever to talk about the field as a single discipline.” As the writers Bernard Leach and Emmanuel Cooper were, de Waal is a potter.

Mary Drach McInnes, “Visualizing Mortality: Robert Arneson’s Chemo Portraits,” in Interpreting Ceramics: Selected Essays, ed. Jo Dahn and Jeffrey Jones (Bath, UK: Wunderkammer, 2013).

Applying medical text and modern painting onto figurative sculpture, Arneson wrenched apart and undermined the mimetic forms of his self-portrait Chemo busts. Studying Francis Bacon’s portraits led Arneson to similarly compromise the human identity in his own portraits. Drach McInnes cites Virginia Woolf, who “wryly notes the inability of language to communicate even simple physical phenomena,” whereas Arneson succeeds in creating “a new text for pain, one that is grounded in the materiality of clay.”

Vilém Flusser, “Pots,” in The Shape of Things: A Philosophy of Design, trans. Anthony Mathews (London: Reaktion, 1999).

Flusser interprets biblical prophecy for our time, that we shall be broken to pieces like potter’s vessels. He complicates the pot that we had assumed was simple. Do we make a pot according to what it is to contain or does the pot define the contents? Do we understand the world algorithmically or heuristically? The security of either approach is a pot to be smashed. Code, or Flusser’s “electronic ceramics,” in-forms content as a pot does—both are hollow. However Flusser lightens up at the end of his essay, offering a prayer for a less ominous interpretation of the prophecy, because “interpretations are put forward in order to be falsified.”

Gwen Heeney, Brickworks (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2003).

The brick is certainly the most ubiquitous aspect of architectural ceramics and one of the fundamental aspects of architecture as a whole. An artist who primarily uses brick, Heeney provides brief introductions to raw materials and ancient brickworks, then closer examinations of technologies and twentieth-century brickworks by artists like Carl Andre, Per Kirkeby, and Charles Simonds. Heeney’s book richly illustrates that magnitude brings us back to architecture and collaboration, connections that ceramics has never forsaken.

Martin Heidegger, “The Thing,” in Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstader (New York: Harper and Row, 1971).

Heidegger’s distinction between the “distancelessness” of, for example, pictures viewed electronically and the “nearness” of things informs our interaction with many things, including ceramics. His description of the void leads him to the jug, his example of the thing that takes, holds, and pours out, thereby gathering his “fourfold”: the earth, sky, divinities, and mortals.

Jeffrey Jones, “A Rough Equivalent: Sculpture and Pottery in the Post-War Period,” ed. Lisa Le Feuvre and Sophie Raikes, Henry Moore Institute Essays on Sculpture 62 (Leeds, UK: Henry Moore Foundation, 2010).

In this lecture, published as an illustrated booklet, Jones extends to postwar ceramics David Sylvester’s claim that sculpture of the same period expressed its humanism through its plastic and susceptible skin versus the “anti-humanism of the streamlined surface.” Though the conventional wisdom is that ceramists functioned communally at that time rather than individually as sculptors did, Jones brings together ceramists and sculptors who share an aesthetic that emphasized rough surface and frontal anthropomorphism.

John Perreault, “Fear of Clay,” Artforum 20, no. 8 (April 1982): 70–71.

Though some critics have written recently about a ceramics presence, this is not new. For Perreault, ceramics may be saddled with more “cons” than “pros,” no matter whether it is seen as new or old, because the fear of the discipline is really the fear of utility, and the fear of the material is really the fear of shit.

Philip S. Rawson, Ceramics (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1984).

Bold statements like this make for entertaining reading: “broadly speaking, one may define the roots of artistic meaning as follows.” Drawing on Henri Bergson, Rawson states that the meaning is the connections of memories and experiences caused by the artwork. Rawson addresses the juxtaposition of “functionalism” and “aestheticism” in broad terms, yet more specifically for the ceramics field than Simmel does (see Simmel entry below). Both Rawson and Simmel, in their own ways, argue for simultaneity regarding art and utility. Despite the title, Rawson quickly limits his subject to pottery because “ceramics [is] the art based upon pottery.” Though “Part I / General Considerations” is the most cited, the diverse discussions of space in “Part III / Symbolism of Form” are recommended.

Anton Reijnders and the European Ceramic Work Centre, The Ceramic Process: A Manual and Source of Inspiration for Ceramic Art and Design (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2005).

After acknowledging the “complex and unpredictable . . . materials and processes,” Reijnders briefly describes the source materials and systematically details how to process them in order to produce all kinds of ceramics. The many artworks pictured all appear to have been made by artists in residence at the European Ceramic Work Centre in s’-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands, where Reijnders was head of studio and workshops from 1991 to 2003. Though less compelling than the images of artworks, the tables and process illustrations are highly useful.

Ezra Shales, “Intervals on the Table and the Pragmatic Standard of Pasta and Peas,” in Tablespace: A Framework for Contemporary Ceramics, exh. cat., ed. Linda Sikora and Albion Stafford (Alfred: New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University, 2011), 16–20. See here, as of November 25, 2014.

Witnessing Mark Pharis and Ole Jensen make ceramics, Shales concludes that absolute distinctions between labels like craft and design are useless. Relying on David Pye to dismiss another “sanctimonious” distinction, Shales writes, “Almost all ceramics sit on the interval between handmade and mass production.” Instead of these binaries, Shales draws attention to another interval, “the space in between us and not the pot as a thing-in-itself,” through Allan Wexler’s 1990 work Coffee Seeks Its Own Level (see www.allanwexlerstudio.com/projects/coffee-seeks-its-own-level, as of November 25, 2014).

Georg Simmel, “The Handle” (1911), trans. Rudolph H. Weingartner, Hudson Review 11, no. 3 (Autumn 1958): 371–85.

Though for Simmel the handle is “perhaps the most superficial symbol” of unity in the duality of human existence, his essay examines, in the most elemental way, how we interact with things that have “double significance” in art and life. “The Handle” was first published in German in 1911. Simmel’s reputation as a sociologist and philosopher has gone through a cycle of dismissal and rehabilitation over the past century.

Jenni Sorkin, “The Pottery Happening: M. C. Richards’s Clay Things to Touch . . . (1958),” Getty Research Journal 5 (2013): 197–202.

A discovery in the Getty Research Institute archive led Sorkin to place Richards’s Happening—a 1958 sale, party, and celebration of her pottery in Manhattan—in penultimate position in the history of the Happening, following John Cage’s Theatre Piece No.1 (1952), in which Richards was a participant. In the context of Richards’s theatrical translations of Erik Satie, Antonin Artaud, and Jean Cocteau, as well as her most important achievement, the book Centering in Pottery, Poetry, and the Person (1964), Clay Things prefigures current social practice.

Pamela B. Vandiver, Olga Soffer, Bohuslav Klima, and Jiri Svoboda, “The Origins of Ceramic Technology at Dolní Věstonice, Czechoslovakia,” Science 246, no. 4933 (November 24, 1989): 1002–8.

Much is often made of how old ceramics is, even though painting is older. Certainly ceramics is the greatest record-keeper through durable objects. Yet the oldest known ceramists, 26,000 years BCE, put the act of making and its social implications over and above the fact of its product. “We must entertain the possibility that these workers were not trying to produce durable ceramic images and that the earliest use of ceramics may have been for their special and unique fire-related properties rather than for a function based on their visual appearances.” Performance with ceramics—forming, then burning, then blowing stuff up—began a long, long time ago.

Hans van Lemmen, 5000 Years of Tiles (London: British Museum, 2013).

The tile is arguably the most important visual aspect of ceramics in architecture. Van Lemmen’s new survey supports technical and aesthetic considerations of Western tiles from the nineteenth century to the present day, with sections on ancient, Islamic, medieval, and Renaissance tiles. Noting the increase in public art projects in tile since the mid-twentieth century, van Lemmen features the contemporary artists Eduardo Nery, Robert Dawson, and Paul Scott, among others.

George Woodman, “Ceramic Decoration and the Concept of Ceramics as Decorative Art,” in Garth Clark et al., Ceramic Millennium: Critical Writings on Ceramic History, Theory, and Art (Halifax: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 2006).

This oft-cited 1979 lecture addresses the conventional agglomeration of “decoration,” “decorative,” “decorum,” and so forth, and the too-swift dismissal by critics of anything to which they might apply one of these terms. Woodman affirms early on the “indulgently permissive” ceramics of the kind now often seen in biennials.

Brian Molanphy is an assistant professor of art at Southern Methodist University (SMU) and a member of the International Academy of Ceramics. Supported by SMU and the Sam Taylor Foundation, he is currently combining pottery, architecture, and Proust in ceramics with fall 2014 exhibitions in Dublin, Ireland; Svaneke, Denmark; Saint-Quentin-la-Poterie, France; and Dallas, Texas.

This critical bibliography originally appeared in the Winter 2014 issue of Art Journal.