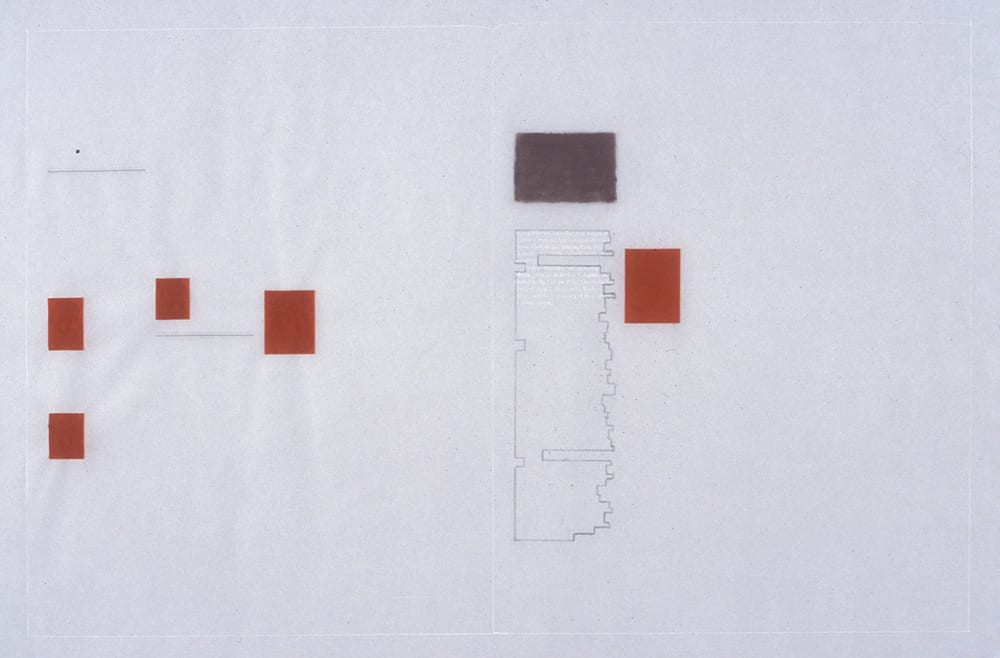

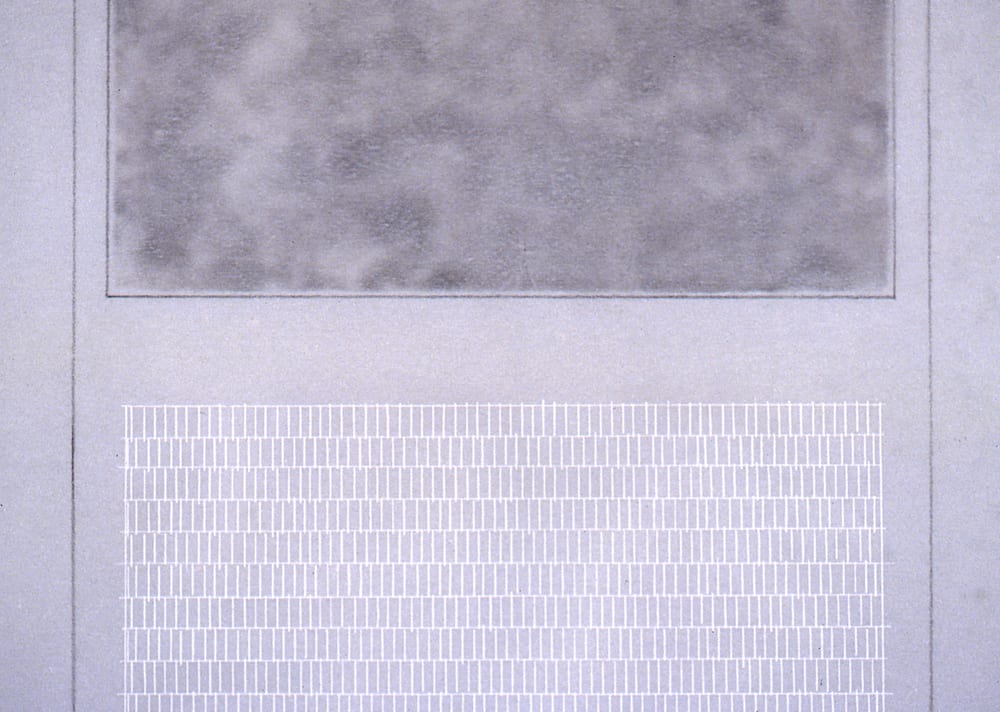

Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, College Art Association News, March 2005, opening, 2005, graphite, pastel, ruby lith, and stylus on vellum, 12 x 18 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff). Collection: Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, New York, New York

In the early 1990s I saw a conference presentation about Agnes Martin’s grid paintings, and their rigor and sensitivity was imprinted on me: I felt motivated to return to making art. When Martin (1912–2004) passed away, I started making artworks to reflect on her work and life, often through printed texts. This has been challenging because she strongly believed that art begins where language leaves off. Though I am sympathetic to her conviction that the vital force of an artwork exists outside language, I live and work with words. So in much of my artwork—not only in the projects about Martin, but also, for instance, in Counter to Type, my Spring 2014 artist’s project for Art Journal—I ask: how can I make visible the palpable pulse in our familiar forms of writing?

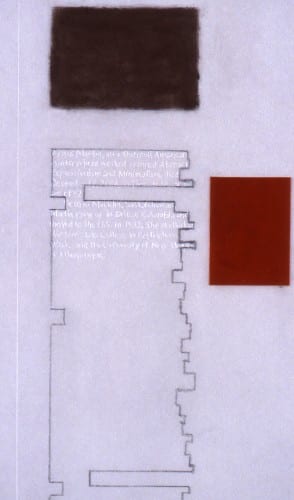

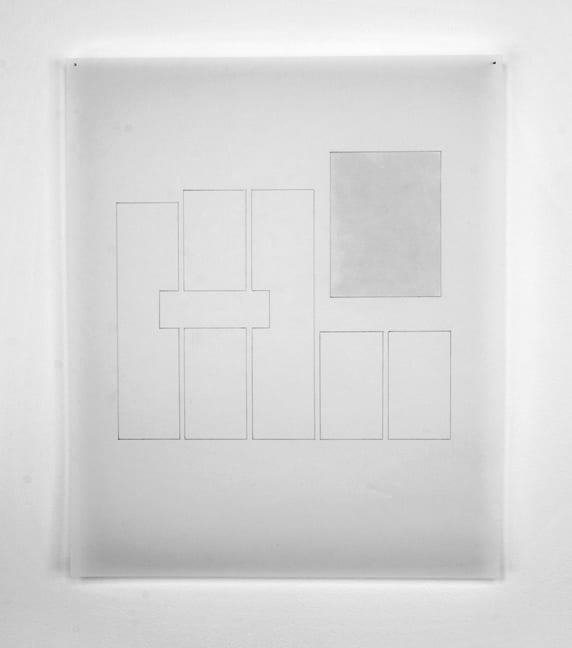

Detail of Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, The Boston Globe, 17 December 2004, I, 2005, tape on vellum, 17 x 14 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff)

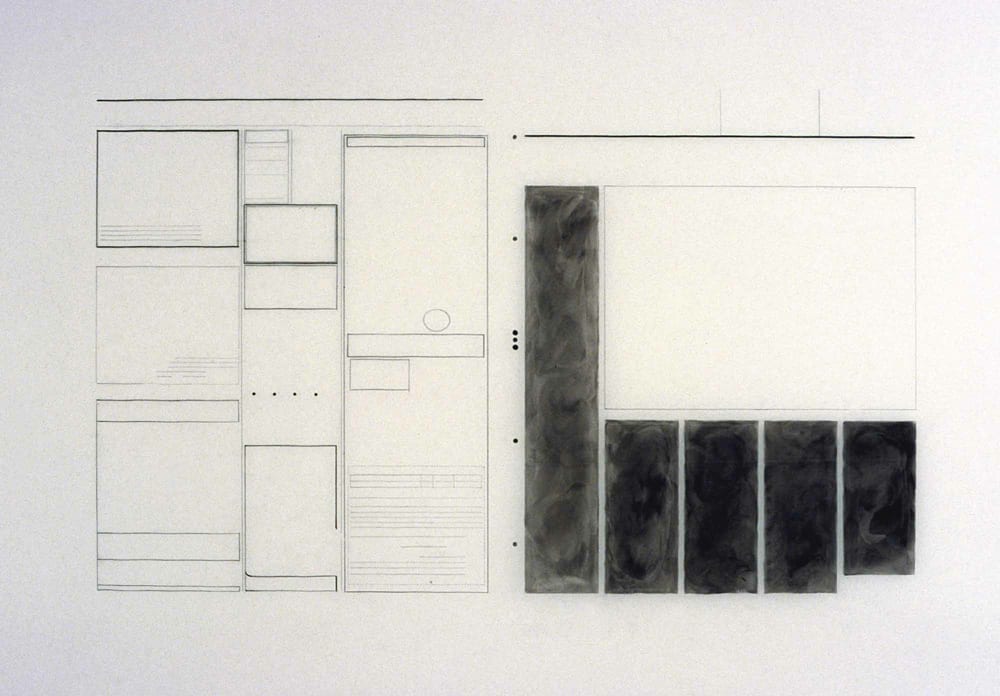

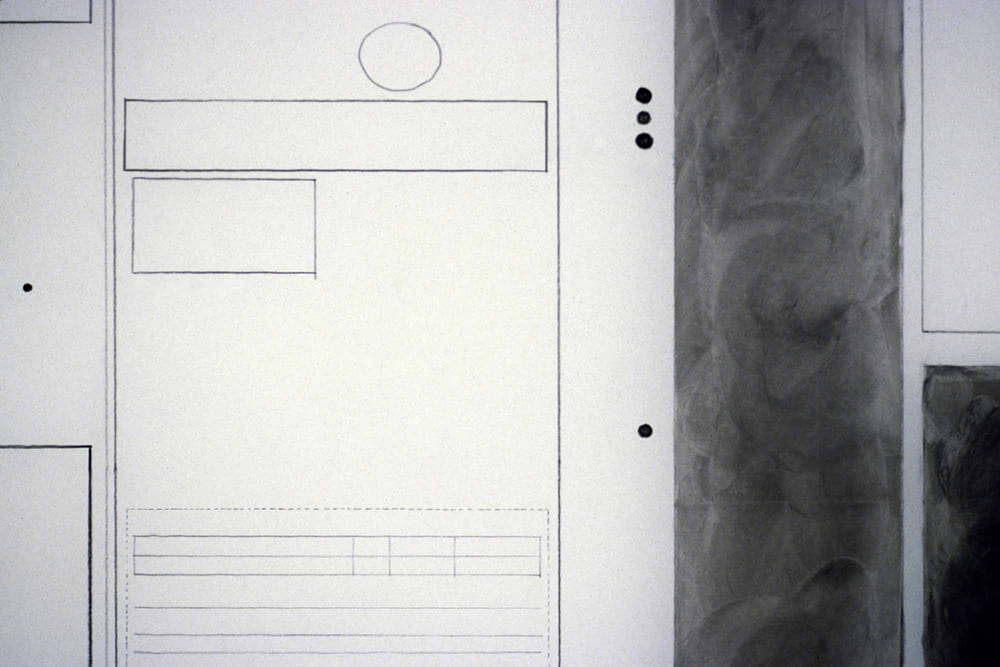

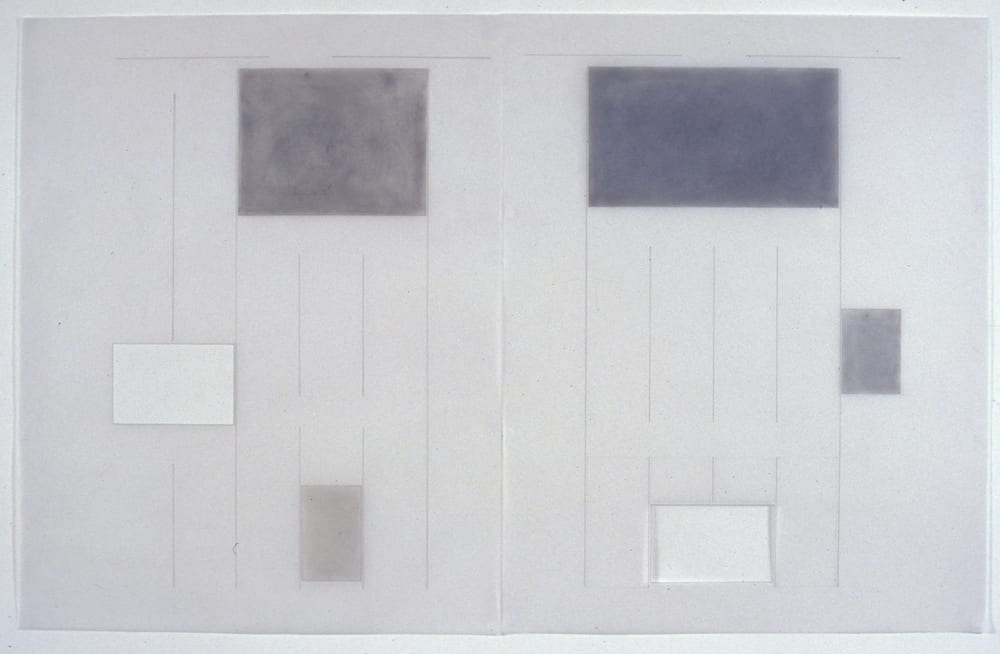

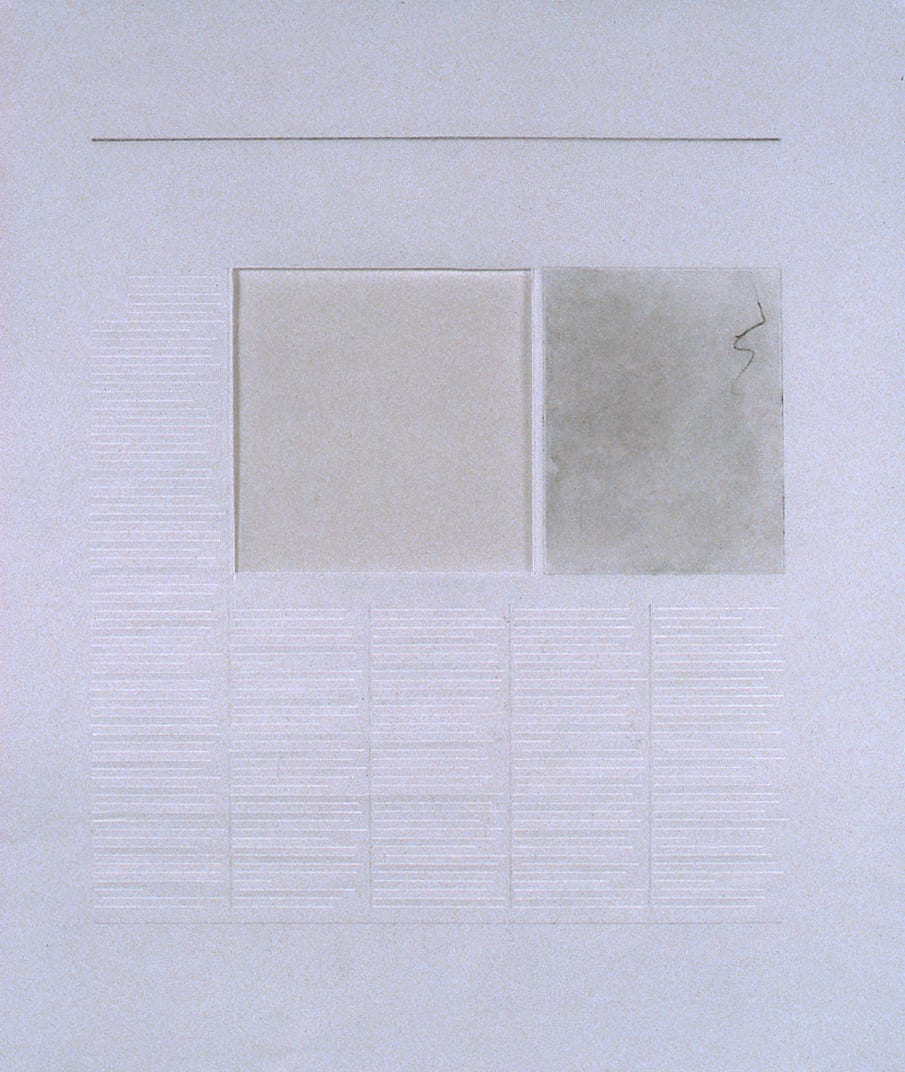

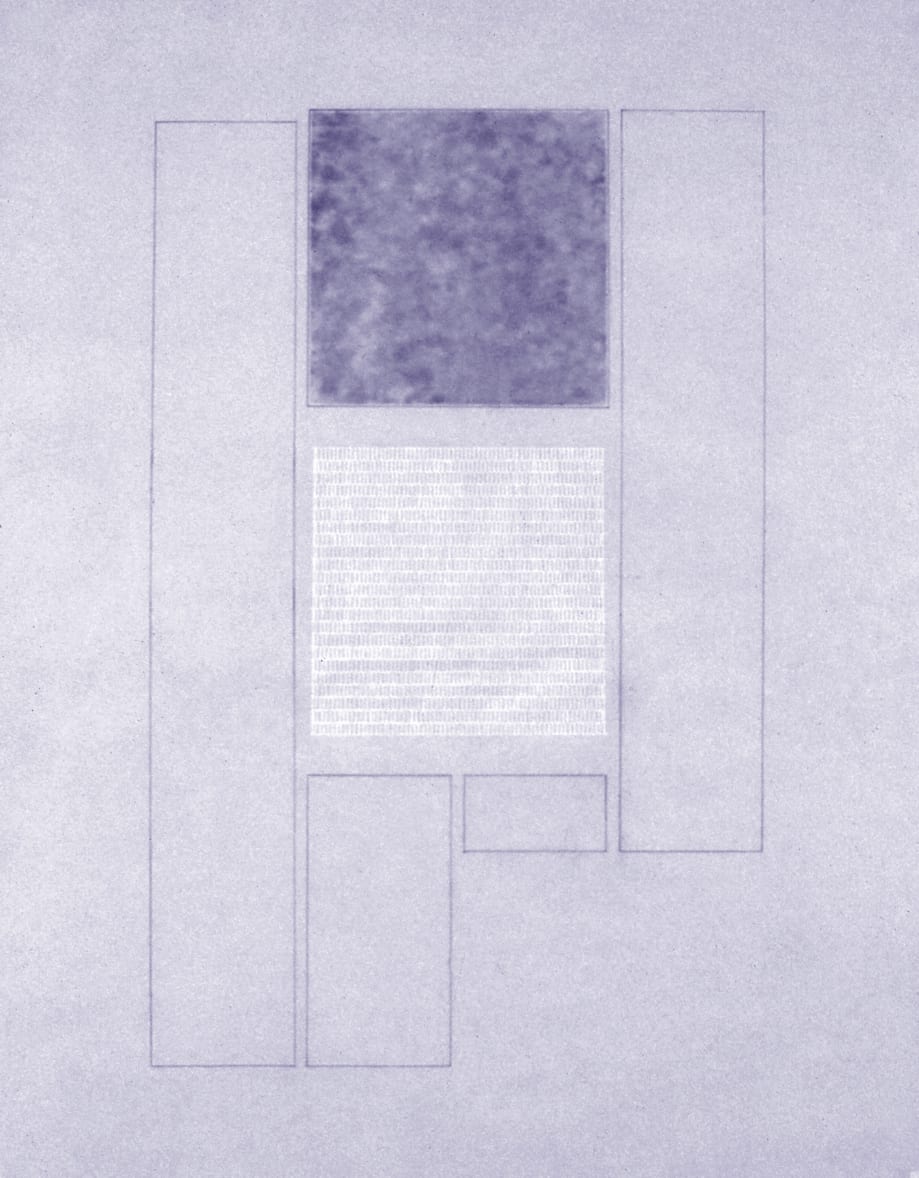

My first attempt to grapple with Martin’s work and life, in visual form, was the (ongoing) Agnes Martin Obituary Project. This series of drawings began ten years ago, in the days just after Martin’s death (December 16, 2004). I was contemplating the obituary for Martin from the December 17th Boston Globe, thinking about Martin and my history with her, and wondering how a life can ever be fully or properly represented in words. (I think the same question can apply to artworks . . .) As my thoughts fogged my vision, I saw the newspaper text as a composition of geometric blocks. These evoked Martin’s own right angles and spacious simplicity, and I realized that I could “read” the article visually. I started making drawings that trace the shapes of all of Martin’s obituary articles, which I gathered from around the world using databases and archives. Martin’s art—and the context of mortality—inform my choices of materials and techniques, though Martin claimed not to have read a newspaper in fifty years. She thought artists should sidestep politics, and avoid the news altogether.

Detail of Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, College Art Association News, March 2005, opening, 2005, graphite, pastel, ruby lith, and stylus on vellum, 12 x 18 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff). Collection: Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, New York, New York

Reading the obituaries underscored my sense that the story of Martin’s career was limited to a few well-worn narratives, so I set out to uncover more facts . . . and sometimes my research resulted in other art projects. In 2006 I received a travel grant to visit the various adobe structures Martin had built in New Mexico; I photographed them and filmed them with a Super 8 camera. In 2007 I returned to New Mexico as an artist-in-residence at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, the town where Martin lived during her final decades. A suite of seven paintings by Martin is permanently installed in a specially designed octagonal gallery at the Harwood; during my residency, I made rubbings of the floorboards beneath each painting. In a similar gesture, I also made frottages from the rubber mat that Martin had stood on while painting, which I rescued from her old studio. Though these drawings are prints, they are not exactly texts. Still, these transcriptions of parallel lines contain evidence—the dust and detritus between the lines—of floorboards, or of the rubber ribs in Martin’s painting mat, that document a history of use and suggest a murky unconscious. I like to think that they reveal the “dirt” that gives Martin’s sublime compositions their underlying foundation, and their fuel.

Karen L. Schiff, catalogue entry for Agnes Martin, New York, New Drawings, 1946-2007. Segovia, Spain: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Esteban Vicente (in cooperation with the Fifth Floor Foundation), 2009

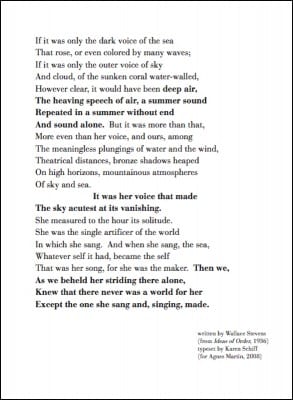

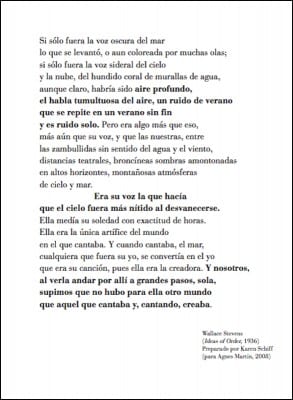

In more recent years, I have grappled with Martin through words. In 2008, when the Kramarsky Collection asked me for a catalogue commentary (in English and Spanish) on a Martin drawing, I created a typographical interpretation of a stanza from a Wallace Stevens poem. Most recently, I have reviewed the groundbreaking books that were published in 2012, Martin’s centenary year. My review of Agnes Martin, the critical anthology principally edited by Lynne Cooke and published by Yale University Press and Dia Art Foundation, appeared in the Fall 2012 issue of Art Journal. And when Martin’s longtime dealer at Pace Gallery, Arne Glimcher, published his compendium Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances with Phaidon, I wrote about it for the June-July 2013 issue of Art in America. In these publications, I aimed for my words to convey the rhythms that move me in Martin’s artwork, so that readers could experience something of her aesthetic. In other words, I tried to imprint something in the texts that would take the reader beyond the words, and back to [Martin’s] resonant art.

Karen L. Schiff, catalogue entry for Agnes Martin, Nueva York: El Papel de las Últimas Vanguardias . Segovia, Spain: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Esteban Vicente (in cooperation with the Fifth Floor Foundation), 2009

This year, I organized Martin’s archive at the Harwood Museum, for easier access and future online circulation. I found more obituaries to trace, and new facts about Martin’s work and life. I am still struck by the inadequacy of words (despite the fact that there are so many), as well as by how much we need them. How can print convey (a) life? Is it not inevitable that invisible forces are imprinted in visible type?

This coming year will bring much more writing on Agnes Martin, in connection with her upcoming retrospective (the exhibition begins in 2015 at the Tate Modern in London, and travels to the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen Museum Düsseldorf, LACMA in Los Angeles, and the Guggenheim in New York). There will be a catalogue, a biography, and other books as well. I have organized a public roundtable discussion of new scholarship about Martin, to be held at Parsons The New School for Design in New York on February 13, 2015, during the College Art Association conference. I hope that my text-art projects add a visual, trans-rational dimension to the writing about Martin, and create an awareness of the nonlinguistic aesthetics—the sensible impressions—which are inherent and active in any text.

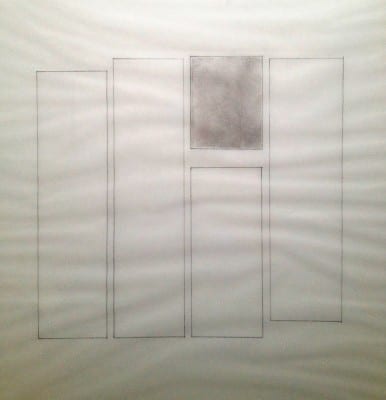

Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, The Times of London, 21 December 2004, opening, I, 2005, graphite and charcoal on mylar, 23 x 34 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff)

Detail of Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, The Times of London, 21 December 2004, opening, I, 2005, graphite and charcoal on mylar, 23 x 34 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff)

Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, Suddeutsche Zeitung, 21 December 2004, opening, I, 2005, graphite, charcoal, pastel, and zip-a-tone on vellum, 24 x 38 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff)

Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, The Boston Globe, 17 December 2004, III, 2005, tape on vellum, 17 x 14 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff)

Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, The Los Angeles Times, 17 December 2004, I, 2005, graphite and charcoal on vellum, 17 x 14 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff)

Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, The London Daily Telegraph, 21 December 2004, opening, 2005, graphite, charcoal, and stylus on vellum, 17 x 14 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff)

Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, The New York Times, 17 December 2004, I, 2005, graphite, charcoal, and stylus on vellum, 17 x 14 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff). Collection: MCS Collection of Contemporary Drawing (Coloção de Desenhos da Madeira), Funchal, Portugal

Detail of Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, The New York Times, 17 December 2004, I, 2005, graphite, charcoal, and stylus on vellum, 17 x 14 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff). Collection: MCS Collection of Contemporary Drawing (Coloção de Desenhos da Madeira), Funchal, Portugal

Karen L. Schiff, Agnes Martin, El País, 21 December 2004, II, 2005, graphite and stylus on vellum, 17 x 12 inches (artwork © Karen L. Schiff)

Karen L. Schiff’s artwork has appeared in the exhibition Art=Text=Art, which has traveled internationally and is now on view in the Anderson Gallery, at SUNY Buffalo, through January 11, 2015. She also has an essay, audio clips, and a curated conversation at the exhibition’s website. In 2013, she curated Winter Reading: Lines of Poetry at the Diane Birdsall Gallery in Old Lyme, Connecticut, and her essay on word-image issues, “Beyond Thinking,” appeared in the Brooklyn Rail. In 2014, her portfolio of manuscript drawings, Unsaid, was published in the e-journal History and Theory: The Protocols, and other text-related artworks were on exhibition at the Hverfisgallerí in Reykjavik, Iceland. For the Spring 2014 issue of Art Journal, Schiff made a video about her artist’s project, Counter to Type, in which she made drawings over some parts of the printed journal.