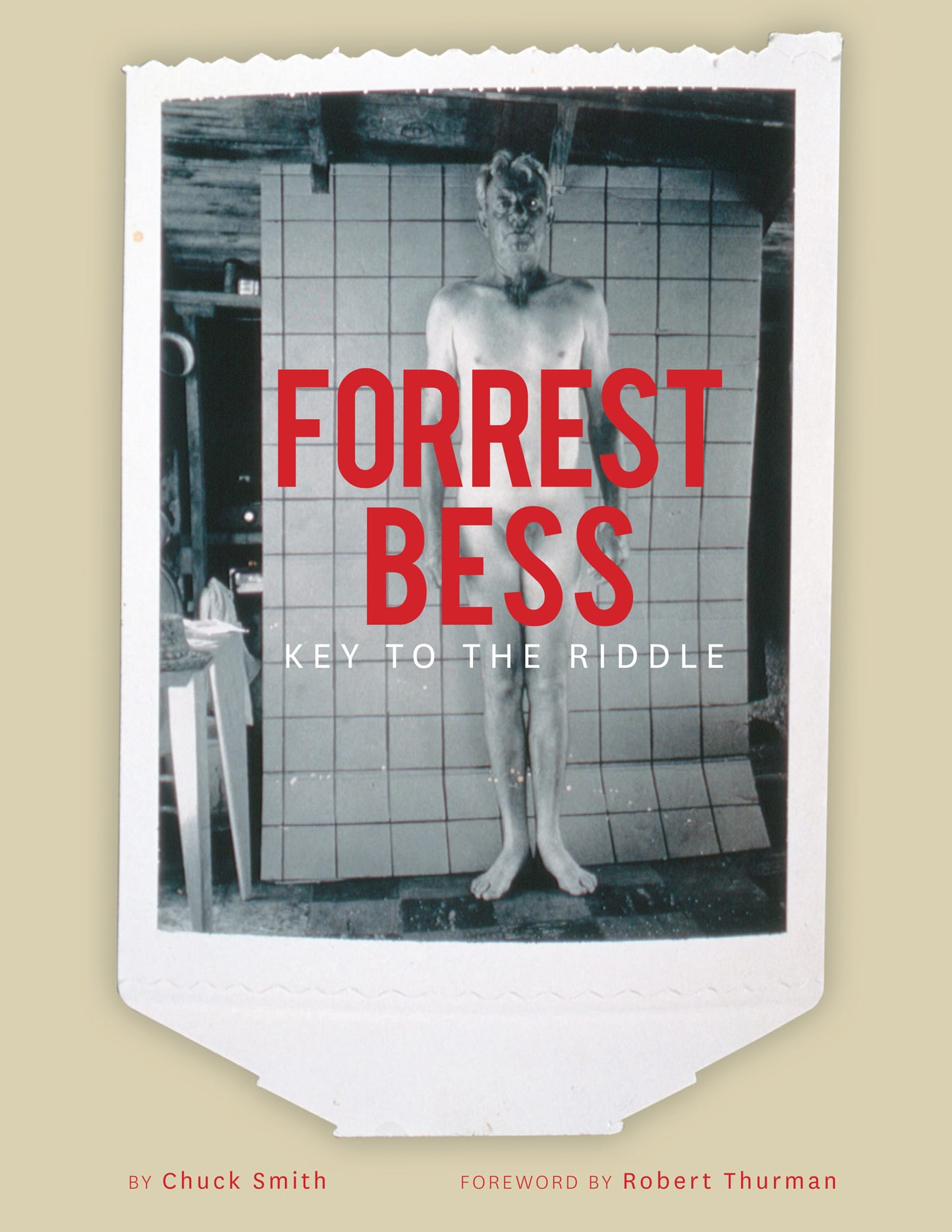

Chuck Smith. Forrest Bess: Key to the Riddle. New York: Power House Books, 2013. 168 pp., 125 color ills. $40

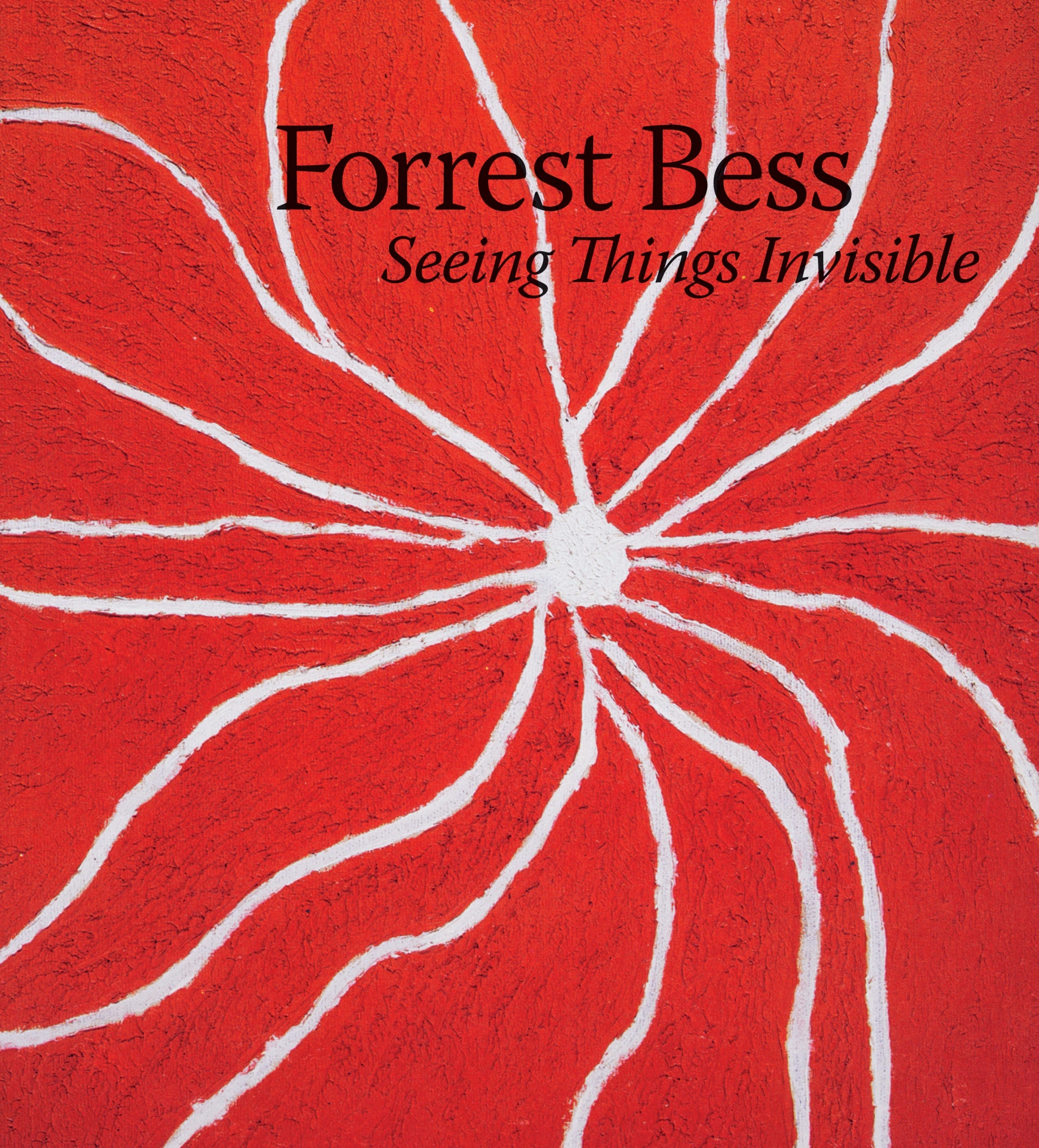

Claire Elliott and Robert Gober. Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible. Houston: The Menil Collection, 2013. 112 pp., 71 color ills. $60

Chuck Smith. Forrest Bess: Key to the Riddle. New York: Power House Books, 2013.

Although mystery has surrounded the life of Forrest Bess since he died in 1977, quite a bit of the cloud is dispelled in Chuck Smith’s new book, Forrest Bess: Key to the Riddle. A follow-up to a film Smith made in 1999, it is an ideal combination of monograph and biography. Copies and quotes from correspondence (found in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art), photos of Bess in his isolated bayou home studio and the watery landscape surrounding it, and numerous plates of his riveting small paintings give a real sense of the life of this extremely arcane artist.

Smith’s intimate knowledge of details is crucial as the story becomes increasingly bizarre. Bess began experiencing visions when he was a child, and after an early period of figurative expressionism influenced by Van Gogh, his paintings were exclusively copied from shapes that he saw in the brief moments when he closed his eyes before and after sleep. Bess also believed that uniting his male and female sides by becoming a pseudo-hermaphrodite would lead to psychic wholeness. His writings include an extensive thesis, marshaling examples culled from religious, mythological, alchemic, and literary texts to support his desire for an opening between his penis and his testicles that could contain another penis.

Bess is perhaps unique among self-taught visionary artists because the purity and originality of his paintings are so familiar to a modernist, reductive sensibility. Non-mainstream spiritual sects such as theosophy influenced many of the inventors of abstract painting, including Vasily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich, but these ideas did not seem to completely dominate their art or life as Bess’s thesis did; nor were they so dangerously physical. The therapeutic nature of Bess’s work, along with his desire for a radical transformation, suggest that he believed that he had to change his material body in order to be able to continue to create.

In addition to the spiritual benefits of becoming a hermaphrodite, which Bess believed would provide unimpeded access to the unconscious and a unified psyche, he hoped that backed-up testosterone would flow into his body, restoring his youth and health. As Smith reports, he was happy to find evidence for this expectation in the research of the Austrian endocrinologist Eugen Steinach, who had experimented with causing the hormone to increase in the body by tying off the vas deferens in rat and dogs, then men, and had published a book with photographic evidence of the regeneration thus produced (Smith, 88–89). Bess believed that such pseudo hermaphroditism could lead to immortality.

The art historian Meyer Schapiro and gallerist Betty Parsons (who also represented Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Barnett Newman) listened to Bess sympathetically, but they were captivated by the simplicity and power of his images rather than by his theories. “These grave little pictures, so broad and firm in conception, have held up over the years,” Schapiro wrote in the catalogue essay for a retrospective exhibition at the Parsons Gallery in 1962. “We cannot read them as the author does; but, undeciphered, we feel the beauty and completeness of his art” (quoted in Smith, 118).

Claire Elliott and Robert Gober. Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible. Houston: The Menil Collection, 2013.

Smith writes in his preface that “I have tried to act more as an editor than a writer; restraining my subjectivity as much as possible,” and indeed a large part of the book consists of quoted letters (6). Thus, Smith does not attempt much analysis of the work, leaving that to Bess and his correspondents. Aspects of Bess’s biography are organized, partially chronologically and partially by theme, including chapters on his theories, his surgeries, and his friendship with Schapiro.

Bess was born in Bay City, Texas, on October 5, 1911. His father was a roughneck, performing skilled manual labor in oil fields, and also selling land leases. Penniless after retiring, he moved to the tiny coastal town of Chinquapin and began selling tiny bait shrimp to fishermen. On his mother’s side, Bess was descended from painters. His grandmother (who died in an insane asylum) made fantastic images that were later destroyed by Bess’s mother and uncle. His mother made naive pictures of houses and trees.

Although he was athletic and did well in school, Bess grew up feeling like an outsider, perhaps due to his growing awareness of attraction to other men. Homosexuality was problematic, since revelation always led to trouble. He confided to someone at home and was ostracized. After spending time working in oilfields and traveling to Mexico, he moved to Houston, where he felt he was too masculine to fit into the gay scene. During the Second World War, he did well in the army until he got drunk and opened up. A homophobe hit him in the head with a pipe, precipitating a nervous breakdown.

After the army Bess lived in San Antonio, where he painted and sold frames, and then moved to Chinquapin to help his father with the bait business. He was happy to get away from other artists and live at the site of his childhood vacations, where he could focus more clearly on his visions. Once there, however, he stayed in the closet to protect his father’s business. Still, he privately embraced his sexual orientation, which he confided in letters to friends. “I swore the day I got out of the army that never again would anyone have the opportunity to use a lead pipe—heels, or blackmail against me for being homosexual,” Bess wrote in 1949 to his Woodstock friends Sidney and Rosalie Berkowitz. “There is no reason to declare to the whole world that I am ‘queer,’ however should I be asked there would be no reason to lie or hide anything” (quoted in Smith, 28).

Bess’s mature body of work began when he decided to paint a hallucination that terrified him during the mental breakdown that followed the army attack. “ONLY BY PAINTING THE goddamned thing out have all my symptoms of anxiety disappeared,” wrote Bess to Parsons. “Now the mind could be given free reign [sic], unfettered. It had unlimited visions which it could call as it wanted them—it could dictate and I would not consciously try to control or create” (35).

Although he painted in isolation, Bess was not a recluse. Between 1949 and 1967, he had six solo shows with Parsons in New York, and he had a number of faithful collectors. A Chicago businessman, Earle Ludgin, bought work and corresponded from afar, while Texas friend Harry Burkhardt and his partner Jim Wilford helped take care of Bess before he died; they amassed a group of forty-five paintings. Bess was always anxious to communicate the meaning of his work, and even published a touching article in the Bay City Tribune, May 9, 1951—quoted in full by Smith—explaining his visionary paintings to his Texas neighbors (36–37). His correspondence with Parsons, Schapiro, and others continued for years. At Chinquapin, where his home could only be reached by boat, visitors and bait customers often arrived; after he moved back to Bay City, his birthplace, Bess became quite friendly with people living nearby.

Inspired by learning of indigenous peo¬ple from Australia who still practice subincision as an initiation rite, Bess finally began his actual physical transformations by cutting into his perineum in 1952, after getting drunk to dull the pain. “I hacked away, scared as hell,” he wrote to Schapiro. “A terrific cramp came in my side, the razor blade slipped from my hand and I was knocked on the floor. . . . But Meyer, the unconscious flooded in beautifully—I had found entrance to the world within myself—a beautiful dimension that had ever been talked about, but not very clearly” (67).

Smith seems to be the only writer to report the full details of Bess’s later surgery, done clandestinely in 1960 by a local physician named Dr. R. H. Jackson, who operated after hours for a fee of six hundred dollars. Subsequently, Bess continued enlarging the opening in his perineum and proudly mailed out photos of the results. Smith also quotes in its entirety a letter by Bess to another frequent correspondent, the sex researcher Dr. John Money (who worked at Johns Hopkins University). Explicit descriptions of his newly possible internal urethral orgasms, both alone and with several partners, demonstrated to Bess the operation’s success (110–11).

Disaster struck in 1961 when Hurricane Carla destroyed Bess’s home/studio along with his larger paintings. He rebuilt, but things were never the same. Skin cancer developed on his nose, and his alcohol consumption increased. He moved back to Bay City to be near his mother; when she died two years later, he became chronically depressed.

Bess stopped painting in 1970 and began to decline rapidly in 1974. His neighbors complained of seeing him partially nude on his porch several times, and eventually he was arrested. To prevent his incarceration, his brother Milton committed him to the San Antonio State Mental Hospital; he was diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenic, partially because they didn’t believe he was a well-known artist. Meanwhile, a show was being planned for the Everson Museum in Syracuse that would travel to the Houston Museum of Contemporary Art; on top of that, Bess was receiving a monthly grant of one hundred twenty-five dollars from the Rothko Foundation.

Five months later, Bess was transferred to the Veterans Affairs Hospital in Waco, and in 1975 he was moved to a nursing home. Friends thought he looked twenty years older than his actual age of sixty-four. His last show was in 1977, arranged by women who belonged to the Bay City Arts League. “Bess came to the opening in a wheelchair,” Smith writes, “and, even though the show was a long way from the galleries in New York, he appeared to enjoy the attention. Ironically, this humble show in a small Texas town was to be his last. Six months later, on November 10, 1977, Bess died of a stroke in his bed at Bay Villa” (138).

Bess’s thesis of hermaphroditism was an outpouring of his core beliefs, and he wanted it seen with his work, but Parsons had always demurred. As she stated in a 1958 letter, “Concerning the hanging of your thesis in your next show, I do not feel I want to. No matter what the relationship is between art and medicine, I would rather keep it purely on the aesthetic plain” [sic] (87). This attitude persisted in the posthumous presentation of his work until the present day.

Four years after Bess died, Barbara Haskell curated a one-person retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York, while a 1984 traveling exhibition brought together Alfred Jensen, Myron Stout, and Bess—three artists whose interest in spirituality was evident in their work. Another large solo show took place at New York’s Hirschl and Adler Gallery in 1988; it later traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, and Museum Ludwig in Cologne. Bess’s work was perceived as a crucial precedent for the sensitive, small-scale abstraction popular with some artists at the time, a reaction, perhaps, against the dominant Neo-Expressionism. Bess’s theories were usually noted in the paintings’ critical reception, but they remained in the background, largely unexplored.

Bess’s work has been rarely exhibited since the 1990s, but in 2012 a single, jewel-like gallery in the Whitney Biennial was hung with his paintings, organized by the artist Robert Gober. Documentary fragments from his now-lost thesis were also on view in vitrines and on the walls, fulfilling the wish Parsons had so vigorously denied. The Biennial also included arcane collages by Richard Hawkins incorporating reproductions of photographs by Hans Bellmer along with writing inspired by Jean Genet, Wu Tsang’s re-creation of a Los Angeles drag bar, and fashion collages by the lesbian activist K8 Hardy. The mystery and singularity of Bess’s images remained, but they acquired an entirely new significance in this context.

At the same time, Houston’s Menil Collection was assembling a large solo show, Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible. The Menil has a history with Bess: after Schapiro introduced founders John and Dominique de Menil to his work, they bought two paintings and joined his circle of correspondents. Since the exhibition was serendipitously planned around the same time as the Whitney Biennial, Menil curator Claire Elliott invited Gober to participate in the show as well, including his documentary material and writing in the exhibition and catalogue.

In her opening section, Elliott writes, “One attempts to avoid stereotyping Bess as a mad genius—to recognize the theories as a major underpinning of the work and acknowledge the surgeries, and their fright¬ening elements of self-harm, without allowing all of this to overwhelm the paintings themselves” (Elliott, 11). Hence, she pays much attention to the work’s physical details. She sensitively discusses materials, along with technique, framing, and the development of ideas. Bess kept a sketchbook by his bed, Elliott explains, to make immediate black-and-white drawings of his visions. After carefully outlining the shapes in pencil on the canvas, Bess applied paint with brushes or palette knives. Colors usually came straight from the tube, but Bess sometimes added sand. Textures could vary from thin to thick or from glossy to matte, and frames were handmade from found strips of wood.

Bess’s stylistic relationship with others in Parsons’s stable is also covered. Although his approach to the act of painting—preconceived shapes painted carefully on small canvases—was diametrically opposed to the Abstract Expressionist preoccupation with large-scale improvisation, an interest in the collective unconscious was common to all. Elliott also notes that Bess’s work did not develop in the same way as the work of artists in New York. His paintings could be very divergent, but his style did not evolve. In contrast to Smith’s single page, Elliott devotes a substantial section to the expanding post¬humous reception of Bess’s work. Taking note of each substantial exhibition, she traces his popularity in the 1980s and attributes the waning of interest in Bess during subsequent decades to the growing predominance of photography and installation. Although gay and lesbian studies became more and more crucial in the art of the 1990s, Elliott also wonders if Bess’s sexuality and theories were too extreme to be assimilated at the time.

A brief contribution to the catalogue by Gober focuses on Bess’s longing to unite male and female within one body; it also helps to realize Gober’s own desire to fulfill Bess’s wish to have his paintings and theories considered as one. Gober’s timing, perhaps, was influenced by the evolution of public attitudes toward gender variation, which, along with transsexuality, has increasingly fascinated contemporary artists and audi¬ences, as transition (surgical or not) from one sex to another (or remaining in between) is no longer rare.

In comparing these two books, it is interesting to note that even after so many years there is still some disagreement about the details of Bess’s life. For example, Elliott claims that Bess met Parsons when he traveled to New York to find a gallery (16), while Smith says he was introduced to her by a friend in San Antonio and the she agreed to give him a show after seeing slides (8). Gober does not believe that Bess found a doctor to do his surgery, or that his opening was ever large enough to accommodate a penis of any size (93), while Smith identifies the doctor who performed the surgery and quotes Bess’s descriptions of the sexual experiences that followed (110–11).

The two books also differ in their production values. The Menil catalogue (appropriately for the record of an exhibition) is elegantly designed, with high-quality paper stock and single-page illustrations of each painting. The paper is heavier, and each painting gets its own page—Smith often places one atop the other, although always in sensitive combinations. But if the Menil catalogue is a more luxurious volume, Smith abundantly satisfies the reader’s curiosity about biographical details that others leave vague. He also provides background informa¬tion on alchemy that readers unfamiliar with such arcana will find useful.

In his journals and correspondence, Bess notated a lexicon of symbols. The collection (culled from letters) reproduced in the Menil catalogue includes simple shapes denoting holes, testicles, anuses, trees, time, and death (Elliott, 100–1). His paintings, as Elliott notes, cannot be so simply inter¬preted, and the relationship between his theories and his practice is enigmatic. If he was simply copying the shapes he saw in his mind, as he insisted, the symbols must have come later—making it seem as if he were trying to fit his theories into his art in the same way he arranged mythology, religion, and alchemy into his underlying grand and almost paranoid narrative of hermaphroditism. Nevertheless, each painting manages to be completely specific and abstract at once— no easy feat.

The conundrum of Bess lies in the con¬trast between the spirituality so crucial to his paintings and the gritty corporeality of his physical transformations. The attraction of his paintings is rooted in the forthright yet modest materiality with which they commu¬nicate Bess’s otherworldly visions, while the disturbing nature of his ideas of hermaphroditism lies in the way they connect the most abject details of sexuality and waste elimina¬tion with the highest allegorical mysteries.

A painting from 1957—The Hermaphrodite—features a red-and-white lozenge floating in the center of a black three-leaf clover shape placed against a field of thickly applied blackish green. The image is mysterious, but on its own it would hardly bring to mind the quotation Smith has placed below it: “In my canvas The Hermaphrodite, then, the membrane has been cut, and we have a view of the stretched urethra—red and white in the form of teeth—the vagina dentata. The curve of the thumb as it stretches the frenum and skin is seen dimly” (Bess quoted in Smith, 101).

Bess often described his self-surgery as an act of self-mutilation, but it could also be seen as a daring act of self-transformation, a willingness to endanger the most vulnerable male parts. Bess considered himself merely a conduit for his visions, rather than an artist, but isn’t that a romantic description of the ultimate state of creativity, when the self disappears and the work flows out by itself? The paintings are compelling and startling. But is it the pull of insanity or spiritual enlightenment that we see? Bess himself did not know. You close your eyes, you see something, and you paint it. What could be more direct? When I close my eyes I see nothing but shadows. Bess saw a blazing world of symbols.

Elisabeth Kley is an artist and writer who lives and works in New York.

This review originally appeared in the Spring 2014 issue of Art Journal.