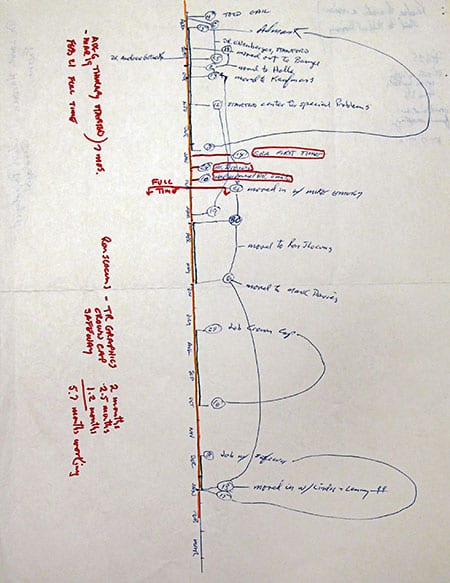

Veronica Friedman, Pages from monthly planners, 1980 and 1981. Veronica Friedman Papers, Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society, San Francisco (photograph © Barbara McBane).

More than a repository of objects or texts, the archive is the very process of selecting, ordering, and preserving the past—in short, of making history. Artists, scholars, and activists have been rethinking the politics of what archives preserve, demonstrating that the piecing together of cultural memory is not a neutral pursuit. The premise that archives constitute that which they purport to document (that archives are, in a word, performative) opens up questions about how archives shape or reshape belief systems and power structures. What do unauthorized, shadow, or dissident archives look like, and how do they operate? How do we engage with archives critically, as representational forms? How have technological and creative innovation reconfigured the power structures that traditional archives uphold? How can we imagine archival practices that exercise poetic license to make the invisible visible, render the unthinkable intelligible, and articulate the unspeakable?

These questions resonate with particular poignancy in outlaw cultures and communities. The queer theorist Ann Cvetkovich has observed that, for queers, the “‘archive fever’ catalyzed by the silencing, neglect, and stigmatization of queer histories is a particularly powerful force, echoing the ferocity and perversity of queer sexual desire. Queer archives, she affirms, are often “archives of feeling.” 1 This is doubly so: queer archival practices are not only propelled by strong feelings, they may also reanimate suppressed histories of sentiment. Quite ordinary things that most people or archives throw away or overlook create, for queers, empathic links to enigmatic pasts.

Queer artists and queer art historians make their way to specialized archives where such odds and ends are preserved, looking for something (or someone) lost, or at least misplaced, in the official historical record. We make pilgrimages to the Lesbian Herstory Archive in Brooklyn, the Fales Library at NYU, the Beinecke Library at Yale, the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at USC, the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco, and the Knight Library at the University of Oregon, among other repositories of queer culture. We also invent new archives. The enterprises of queer artists, historians, archivists, and curators train creative focus on people who are underrepresented in traditional archives, and thus histories—queers, women, people of color, “aliens.”

At the 2012 CAA annual conference in Los Angeles, the Queer Caucus for Art sponsored a ninety-minute session titled “Conversations on Affect and Archives.” Virginia Solomon, cochair of the caucus, and I invited three discussants whose work engages with archives to participate: the art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson, the historian and curator Jeannine Tang, and the artist Catherine Lord. At our request, each recruited a colleague to dialogue on the topic of queer affect and archives. Julia invited the documentary filmmaker Cheryl Dunye; Jeannine invited Thomas Lax, of the Studio Museum in Harlem; and Catherine invited the artist Eve Fowler, cofounder of Artist Curated Projects. This issue of Art Journal provides a forum for an expanded roster of participants to examine the archive as both a resource and a conceit.

Tirza True Latimer is associate professor and chair of the graduate program in visaul and critical studies at California College of the Arts in San Francisco. Her published work reflects on modern and contemporary visual culture from lesbian feminist perspectives.

This essay originally appeared in the Summer 2013 issue of Art Journal.

- See Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003). ↩