Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974. Exhibition organized by Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, May 27–September 3, 2012; Haus der Kunst, Munich, October 11, 2012–January 20, 2013

Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon, with contributions from Tom Holert, Jane McFadden, Julian Myers, Emily Scott, and Julienne Lorz. Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974. London: Prestel, 2012. 264 pp., 270 color ills., 197 b/w. $60

Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974, the bold title of the exhibition and catalogue organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and on view there in 2012 and later at Munich’s Haus der Kunst, evokes the grand ambitions of artists’ environmental imaginations in the early 1970s. At the same time, its suggestion of an expansive sweep announces the aspirations of the exhibition’s organizers, the MOCA curator Philipp Kaiser and the UCLA professor and author Miwon Kwon. Encompassing two hundred fifty works by more than ninety international artists—most of whom have never in the art-historical literature been considered Land artists—with a hefty accompanying catalogue, this project’s composition and textual representation summon at the outset the scale and monumentality connoted by the term “land.”

At MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary, the view from the raised platform dividing lobby from exhibition was of a warren of white-walled open cubicles and, at the left, the mezzanine gallery. Below ran a large-screen projection of the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely’s controlled explosion in the Nevada desert of Study for the End of the World, No. 2, the sculpture made from odds and ends rummaged at Las Vegas scrap yards. Its date of 1962 is at least four years before the artists customarily associated with earthworks or Land art (first, the New York artists Walter De Maria, Michael Heizer, Robert Morris, Dennis Oppenheim, and Robert Smithson; the London-based Richard Long, and Amsterdam-based Jan Dibbets; then other Americans including Alice Aycock, Agnes Denes, Nancy Holt, Mary Miss, Charles Ross, Michelle Stuart, and James Turrell, among a few others) made their first works in, with, or directly atop soil, either in uncultivated rural terrain distant from those cities or, a few years later, on institutions’ grounds. For the informed viewer, the placement of an assemblage work by a Nouveau Réaliste artist at the show’s entrance signaled the organizers’ intent that the field of Land art be not just expanded, but blown wide open.

Thereafter, past a mural photograph of Isamu Noguchi’s tangential 1947 Memorial to Man—geometricized male facial features rising from a pebbly moonlike surface—a clear route through the installation’s dense forest of chambers, shelves, and cases vanished. Photographic documentation, drawings, films, and videos represented environments, constructions, or performances originally produced outdoors; some gallery-scale works, often made originally in temporary formats of impermanent matter, were reconstructed. No wall texts announced sectional groupings. Nor was there, on the wall or in a handout, a curatorial statement of intention, a rationale for the exhibition’s chronological parameters (an indistinct beginning and an early termination at 1974), or a contextualization of the work in relation to the social and political tumult and influential cultural changes strongly associated with those years. Instead, a paragraph of material explanation and art-historical biography followed most works’ wall labels. (These texts, along with a photograph of every work on view, are fully reproduced in the catalogue’s annotated checklist, making it a useful resource.) Thereby, the exhibition’s meaning was atomized to individual acts.

Lacking the structuring guidance customarily provided in museum exhibitions, the viewer was left to wander and wonder about the best way to absorb the panoply of what appeared to be every radical or somewhat clever machination with natural elements undertaken by artists through the mid-1970s. Almost. The exhibition did not acknowledge the absence of work by two titans of Land art, Walter de Maria and Michael Heizer; the curators wrote in the catalogue that these artists “have insisted that their work is only ‘out there’ and therefore declined to participate in this exhibition” (30).1 Jannis Kounellis and Harvey Fite were also missing.2

In fact, like invitees whose absence from a party is talked about all night, De Maria’s and Heizer’s decision not to exhibit garnered them more frequent and extensive pictorial and textual representation in the catalogue than any other artist. They are not just mentioned as relevant historical figures: Tom Holert discusses work by both; Jane McFadden analyzes work by De Maria; Julian Myers’s essay centers on a work by Heizer; essays by the Germans Laszlo Glozer, a critic, and Julienne Lorz, a Haus de Kunst curator, do not analyze their country’s manifestations of Land art but focus on works the two American artists produced in Munich; and the artists’ patron Virginia Dwan praises them and paraphrases their ideas.

Thus, the revision the curators seem to have in mind is of the historical stature of Smithson. The number of major monographs and exhibitions focusing on Smithson and the manner in which he is discussed in histories of this movement make him the predominant Land artist in the literature; certainly he articulated the genre most actively in essays and interviews. Yet his work is only tangentially incorporated into the history presented in the book. That would have been appropriate if the curators had acknowledged Smithson’s prominence in the development of Land art and declared it irrelevant to their own emphasis. But without that, his contributions appear slighted and, cued by Kaiser and Kwon’s insupportable accolade of Heizer’s Double Negative as “arguably the most iconic piece of Land art,” deliberately so (11). With a claim like that, both appearing in their first paragraph and so easily refuted by simply counting on Amazon the number of texts on and book cover illustrations of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, far greater than those of any other work of Land art, the informed reader gets an uneasy sense that however much we acknowledge the impossibility of absolute objectivity, something other than impartial scholarship is in play.

While the overall structure of the labyrinthine installation was difficult to discern, works originally exhibited in the Dwan Gallery’s Earth Works show (October 1968) in New York, and in Willoughby Sharp’s Earth Art exhibition (February 1969) for Cornell University’s Andrew Dickson White Museum were roughly arranged together. These were interspersed with works such as Ross’s Solar Burn series (1971), which had been in neither show. Nothing revealed the rationale for the corner wall behind Morris’s Earthwork AKA Untitled (Dirt) pile beinguniquely egg-yolk yellow. Understanding that anomaly required a historian’s esoteric knowledge: De Maria, in designing The Color Men Choose When They Attack the Earth, selected the vivid hue of Caterpillar earth-moving equipment for his “delegated painting” that in Earth Works hung behind Morris’s twelve-foot-diameter mound of soil, pipes, felt, and grease.3 Thus the yellow’s allusion cunningly circumvented De Maria’s absence.4

Another curatorial decision that called for explanation: women artists, representing different artistic generations and working in a range of styles (Aycock, Judy Chicago, Denes, Holt, Patricia Johanson, Joan Jonas, Mary Kelly, Ana Mendieta, Miss, Maria Nordman, Yoko Ono, Stuart, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles) were almost entirely grouped at the back of the hall, diagonally opposite the entrance. Was that a nod to a chronological understanding of this genre’s development? Neither Earth Works nor Earth Art included a woman artist; in my book Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties, I discussed the omission of women from 1960s shows, but noted their increasing involvement in the field by the 1970s. While Aycock is represented in Ends of the Earth by works made 1971–73, Mendieta by performances 1972–74, and Ukeles by symbolic actions in 1974, it would have been more consistent with the show’s revisionist aim to integrate earlier works by women, such as Chicago’s Atmospheres performances (1967),Holt’s Stone Ruin Tour, Cedar Grove (1968), Jonas’s silent film Wind (1968), and Stuart’s late 1960s earth-lined pine boxes titled Earth Diptych, among contemporaneous works by males. Also undermining revisionist aims, the catalogue texts do not analyze at any length works by female sculptors (except, tangentially, Niki de Saint-Phalle, wife of Tinguely).

The unexplained spatial contiguity of chronologically or conceptually disparate works illustrates the installation’s eclecticism. Some artists were grouped according to their appearance in canonical Land art exhibitions, and others by gender or nationality, by formal or procedural similarity such as pile-making, or by pragmatic technical needs such as large projection spaces. The sheer variety of materials, procedures, and intentions regarding international sculptors’ incorporation of earth, air, fire, or water into their art between the late 1950s and the early 1970s that seems to have stymied a clear curatorial narrative also thwarts the viewer’s comparative comprehension. Was one to understand from the installation’s lack of categorical or thematic structures that everything on view in Ends of the Earth is ipso facto Land art? Viewed historically and stylistically, some is prior sculpture, some is proto–Land art, some performance with natural matter, and some, such as that by the Slovenian OHO Group, distinctly Land art but just as obviously, downright derivative of Long and Oppenheim. Consequently, the curatorial process itself uncannily demonstrated Hal Foster’s observation, “In its very heterogeneity, much present practice seems to float free of historical determination, conceptual definition, and critical judgment.”5

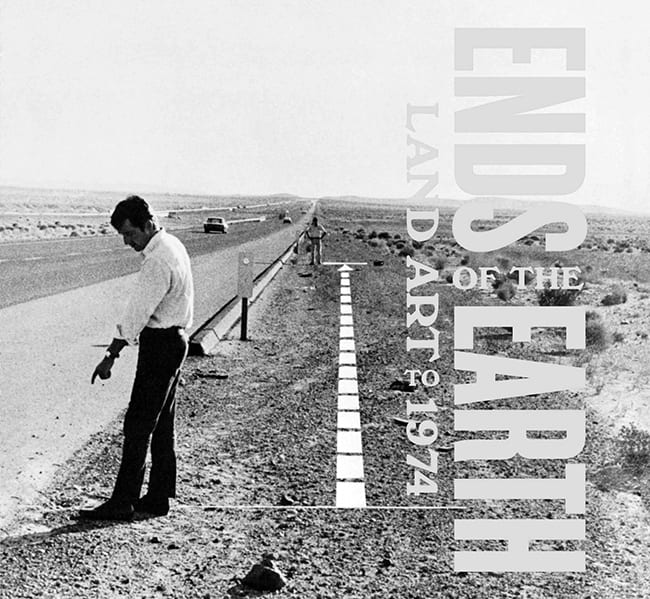

Fortunately, the catalogue aids in making sense of Kaiser and Kwon’s achievement in curatorial hunting and gathering. First, the tome is gorgeous. It is well designed overall and in the balance of text and white space on each page. Its selected bibliography, annotated checklist, and annotated chronology of exhibitions and events, including exhibition rosters, major published reviews, and significant dates in individual artists’ oeuvres, are valuable resources. There’s that yellow again, albeit a bit more tawny, on the thick end-papers and even more prominently as the font color used for the cover, a striking contrast to the rich gray tones of the cover’s vintage photographs. The front pictures a 1967 road trip taken by Los Angeles’s favorite son Edward Ruscha, along with Patrick Blackwell and Mason Williams. The back cover shows a sign planted in the Nevada desert by Tinguely, reading “End of the World.” Together, the cover images evoke the Western perspective enclosed within—and, as neither Ruscha or Tinguely is a Land artist and they have probably rarely if ever participated in the same exhibition, the show’s eccentricity.

In their introductory essay, “Ends of the Earth and Back,” Kaiser and Kwon assert four claims “that counter the most common myths associated with Land art” (19). The first of these, “Land art is international,” corrects the historical understanding retrospectively articulated in this catalogue by Glozer that in the 1960s Land art was “accepted as a largely ur-American phenomenon of new art” (176), a notion perhaps still held by the public, but not by scholars of the genre.6 More precisely, the curators demonstrate that artists’ work in or with natural matter and related (if mostly tangentially) to Land art was much more international¾ extending far beyond the East Coast/Western European hegemony of contemporary art—than anyone has previously discussed. American artists represented a little over half the roster of Ends of the Earth. Eight artists were from the United Kingdom; seven from Germany; five each from Italy, Japan, and South America; four each from France and Israel, and three from the Czech Republic, among other places. (In her essay “Along the Way to Land Art,” McFadden analyzes intermedia work with earth by Nouveau Réaliste, Fluxus, and Group Zero artists, deftly establishing the exploratory vivacity and social complexities of the early 1960s.) The great number of far-flung instances of artists’ work regarding land or made with natural materials in the 1960s and early 1970s that the curators discovered prompts two basic questions. First, can these instances be attributed to diffusion from art-world centers, or do they constitute discrete geneses? Second, in either case, what are the reasons for this avalanche of earthworks? What specific ideas during these years united these “heterogeneous practices” and “diverse artistic objectives” (Kaiser and Kwon,18)?

Confronting these questions seems not to have been the curators’ intention, which they describe as “an epistemological inquiry that returns to both artistic and curatorial activities in the 1960s and 70s to glean the conditions that contributed to the favorable promotion of Land art as a viable new art category” (19). This “meta” art history—an intra-art inquiry into artists’ and curators’ conceptualization of land art and its presentation in exhibitions, with minimal extra-art cultural or historical contextualization—explains the presence of statements by curators and historical accounts of exhibitions in Detroit, Munich, and Tel Aviv. However, the aim of telling how Land art became a “category” needs more direct analysis of contemporaneous artistic theories and practices than is offered in this volume. They link the 1974 endpoint to Artpark’s commissioning of outdoor sculptures in Lewiston, New York, and to the exhibition Probing the Earth: Contemporary Land Projects at the Hirshhorn in Washington, DC, the first retrospective Land art survey, which “marked Land art’s full institutional arrival,” as the curators remark in a footnote (31). But that show didn’t take place until 1977.7 Overall, their argument for using exhibition dates and “institutionalization” to establish an endpoint for Land art and their exhibition is too vague, and is mostly provided in footnotes. Their adoption of 1974 as their cutoff date not only contradicts history but weakens their own argument, as it precludes recognition of the impact of institutional and agency funding in the production of significant works of Land art subsequently initiated, completed, or still in process by Aycock, De Maria, Heizer, Holt, Miss, Morris, and Turrell.

Kaiser and Kwon’s second assertion, “Land art engages urban grounds,” dismisses a simplistic “myth of Land art’s antipathy to the city” by asserting, reasonably, the relational duality between urban and rural (21). This is dynamically demonstrated in Emily Eliza Scott’s essay, “Desert Ends,” which reveals the American desert not as unmarked purity but, for example, “in addition to allowing Tinguely to ‘build as big’ and ‘destroy as violently’ as he wanted, operated most precisely as a restaging ground for the mediated atomic tests the artist intended to critique” (82). This deeply researched and compellingly written treatment adds necessary recognition of concurrent political history. Another engrossing essay, by Myers (like Scott, a distinct authorial identity from whom we can look forward to reading more), uses the Detroit location of Heizer’s Dragged Mass Displacement, commissioned in 1971 by the Detroit Institute of Arts, as an opportunity to range widely over the terrain of the urban/desert dyad. Writing in a poetically allusive voice, Myers observes, “Earthworks were marked by their dream of an elsewhere where some stand against the urban, the social, the human might still be made. . . . But this was a dream from which the artists are always waking: the reality of the modernized desert was always looming” (143).

Third, “Land art does not escape the art system” (22). Again—so true! This was evident as early as 1971 when Dave Hickey complained, “Why have the national art magazines both overrepresented and misrepresented the earthworks movement and its related disciplines, choosing to portray them as a kind of agrarian Children’s Crusade against the art market and museum system, when this is obviously not the case?”8 All of the texts here implicitly validate this assertion. But as historians and critics continue to misconstrue sculptors’ spatial desires to “get out of the gallery” simply as a rejection of the art world’s mercantile system—a look at artists’ gallery associations indicates otherwise¾it would have been beneficial if the curators had offered an essay directly countering this cliché.

Their fourth claim, “Land art is a media practice as much as a sculptural one” (27), put forth by Holert in his essay “Land Art’s Multiple Sites,” points to an overlooked aspect of much of this work. The curators’ highlighting of the distinction of media viewed “not so much as a representational surrogate for ‘the work,’ but as a relay or extension of it” (30) is one of their most illuminating contributions to how Land art is viewed, and Holert’s essay provides convincing evidence.

Additionally, the interviews with and statements by historical figures give voice to those who enacted this history. But roughly forty years after the events they recount, the recollections by those who have given numerous interviews and read others’ narratives are hardly more “primary” than historians’ syntheses of the archives. Here, the rewards of reading first-person accounts are undermined by the absence of editorial acknowledgment of the inconsistencies that arise. Sharp boasted of his own exhibition, “Perhaps the most important thing about the Earth Art show was that it was the first exhibition to really trust artists to deliver work and to do that at the museum, in situ” (38). In his ensuing remarks, it is clear Sharp meant that the artists would “deliver the work” by making it on site from indigenous matter, as they did. Still, that “first” would be a surprise to readers of the following interview, in which the artists’ representative and sometime dealer Seth Siegelaub recalls an outdoor show he helped organize ten months prior, and remarks, “Carl [Andre] . . . had traditionally often worked from materials that he found wherever his works were made” (62). Both are mistaken. At that point, Andre had done such a thing only once, and not by finding materials but by having metal pieces fabricated in Düsseldorf instead of shipping completed work there for his solo show with Konrad Fischer in November 1967. The Andre show to which Siegelaub refers would be his outdoor debut; his Joint resulted from Andre’s discovery, according to Charles Ginnever, the sculptor and then director of the Windham College gallery in Putnam, Vermont, the site of Siegelaub’s show, that “he could buy a ton of mulch hay for $50,” the amount Ginnever allotted each artist.9 Yet neither of these was the first occasion of the curatorial practice of transporting the artist, not the art, to produce work on site.10 In his account in Ends of the Earth, Siegelaub doesn’t mention Ginnever, and neither do the editors.11

Sharp also misstates the circumstances of the removal of De Maria’s rectangular carpet of earth that the artist made on the evening of Earth Art’s opening, inscribing the soil with the words “Good Fuck.” In transcribed remarks that Kaiser and Kwon edited from an oral-history video (Sharp died in 2008), he states that “as soon as [the Cornell museum director] Tom Leavitt saw that and realized that there were kids at the opening as well as the president of Cornell, they cordoned off the room . . . and the next day, the piece was swept up and dispersed” (39). Observant readers will note that Good Fuck is pictured opposite the first page of Sharp’s text in Ends of the Earth, in a clipping from the Ithaca Journal dated February 22, 1969, that does not mention the room having been closed off or the work removed (36). Flipping back to the catalogue’s annotated chronology, the show’s opening is listed as February 11 (250). A different account of the removal of De Maria’s work is Leavitt’s (and mine): “When a few days [after the opening] Leavitt informed De Maria that the museum planned to close off that room during an elementary school group’s visit, the artist withdrew from the show. Heizer, presumably acting in solidarity, withdrew from Earth Art at the same time.”12

Two pages are devoted to large photographs of Dwan as a youthful gallery owner, the sole woman socializing with two sets of six men (25, 55). Dwan’s autobiographical essay offers a dealer and patron’s testimonial that De Maria, Heizer, Ross, and Smithson are the “high priests of Land art” and expresses sympathy for the difficulty in realizing “a comprehensive museum exhibition about Land art without their blessings” (93). This vintage conception of artistic genius seems in contradiction with the exhibition’s international and trans-stylistic aims. Also, Dwan asserts that she “must also espouse the sentiments of De Maria and Heizer that the photograph is not the work” (95). Not only is this an unnecessary refutation of an obsolete axiom, but also, the elusive artists already negated their refusal to participate in this endeavor by allowing images of works to be included in its catalogue. And Holert’s insight that “in the case of Land art, the popular magazines not only functioned as media of reactive reception but also routinely acted as (not always welcome) coproducers of the phenomenon” (100) persuasively challenges the idea of discrete antinomies of Land art and its media representation. (Unfortunately, neither Dwan nor other writers here extend their recognition of the importance of private patronage in getting these distant and large works done to acknowledging Robert Scull’s prescient funding of De Maria’s and Heizer’s prior projects. Scull funded Heizer’s contribution to Dwan’s Earth Works show, from which he also purchased De Maria’s painting.)

The lack of editorial annotation of the inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and omissions in these personal accounts impairs this volume’s scholarly credibility. In their own essay’s notes, Kasier and Kwon do augment the television producer Gerry Schum’s association with the term “Land art” by acknowledging De Maria’s prior use of it (17).13 But throughout, the reader has no way of determining whether the editorial silence regarding the discrepancies between the various historical and scholarly accounts should be attributed to lapses in historical knowledge, to a blindness to others’ directly pertinent scholarship, or to the attitude (increasingly seen in political discourse) that first-person subjectivity trumps factual accuracy. The curators’ leniency is consistent with their free interpretation of the genre of Land art—expanding it in the exhibition to reveal relevant work by numerous international sculptors as well as to include artists whose practices are chronologically or procedurally outside the customary domain of Land art, such as Yves Klein, Adrian Piper, and Lothar Baumgarten; compressing it in the catalogue to focus on Tinguely, De Maria, and Heizer; and stopping it before almost all of the major works of Land art were erected.

Lastly, there’s an elephantine lacuna in this project’s handling of earthen matter and natural processes. The aspect most fundamentally uniting these artists is their involvement with land and biotic matter, e.g., earth. This word is an age-old synecdoche for wider “nature” as both place and process, yet the artists’ use of and cultural consciousness in relation to it is not addressed. An essay contrasting the onset of social and political environmentalism in the 1960s with the common artistic practice of using land and earthen material as cheap, hardly monitored expanse and malleable dirt would have confronted issues crucial to both then and now. For those viewing this exhibition in California, the state that leads the nation in the stringency of environmentally beneficial regulations (its other venue, Germany, is another world leader in that regard), and during a summer of wildfires in Colorado and New Mexico, flooding in Minnesota, and drought in the Midwest leading to the desiccation of the nation’s corn crop, the titular convergence of the words “earth” and “ends” might conjure the climatological catastrophe in process. Actually, the prominence of Tinguely’s “End of the World” sign on the catalogue’s back cover can be taken to signal this project’s political unconscious—the recognition that consequent to climate change, the end of our experience of land as we have known it really is at hand. If the latent had become manifest, the curators could have also begun correcting art history’s scanty engagement with ecocriticism.[14. For reference, see Lawrence Buell, The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination (Malden, MA, and Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2005); The New Earthwork: Art, Action, Agency, ed. Twylene Moyer and Glenn Harper (Hamilton, NJ: ISC Press, 2012); Linda Weintraub, To Life! Eco Art in Pursuit of a Sustainable Planet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012); and Third Text 120, spec. issue “Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology,” ed. T. J. Demos (January 2013). Notably, the institutional pioneers exhibiting such work are largely European; the exhibitions include, among many others, Radical Nature: Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet 1969–2009 (Barbican Art Gallery, London, 2009),and Greenwashing Environment: Perils, Promises and Perplexities (Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, 2009). No major American museum has organized a comparable exhibition; important recent surveys at smaller venues include Beyond Green: Toward a Sustainable Art (Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2005–6), and Weather Report: Art and Climate Change (Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007). Curators, as forces of culture, are needed to help show which way the wind blows.

On behalf of the College Art Association, Erica Hirshler, chair, and jurors Andrea Bayer, Phillip Earenfight, Lisa Saltzman, and Anne Woollett selected Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974 as recipient of the 2013 Alfred H. Barr Jr. Award for distinction in museum scholarship.

Suzaan Boettger, a New York City–based art historian, critic, and lecturer, is an associate professor at Bergen Community College, New Jersey. The author of Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties (University of California Press), she contributed a text on “The Impetus of Ethics” to the forthcoming Artists Reclaim the Commons: New Works, New Territories, New Publics, ed. Glenn Harper and Twylene Moyer (International Sculpture Center, May 2013). Her book in process is Climate Changed: Contemporary Artists’ Environmentalism.

- Directly experiencing those two artists’ work “out there” requires MOCA visitors to drive 689 miles from the Geffen to Quemado, New Mexico, for De Maria’s Lightning Field during the months of the year that it is open (the guest cabin sleeps six, and visitors are driven to it and sequestered for a stay of approximately twenty-two hours) or 331 miles to Overton, Nevada, if one has a four-wheel-drive vehicle that can surmount the mesa of Heizer’s Double Negative, which, despite the absence of its pictorial representation in the MOCA show, MOCA owns. However, De Maria’s and Heizer’s work is extensively illustrated “in there”—in the exhibition catalogue. ↩

- On Fite’s work, see Donal F. Holway, “Sculptor Nearing an End of Massive 40-year Task at Abandoned Quarry,” New York Times, August 3, 1968, 27. The article appeared two months before the Dwan Gallery Earth Works exhibition. See also my own book, Suzaan Boettger, Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties (Berkeley: University of California Press),147. ↩

- Toby Kamps, a curator at the Menil collection, which now owns the De Maria painting, told me that MOCA color-matched its yellow installation walls with the painting. Kamps e-mail to the author, August 10, 2012. ↩

- De Maria actually was in the show if one counts his film Two Lines Three Circles on the Desert (1969); it was among the artists’ films in Gerry Schum’s Land Art broadcast in 1969 and was shown on a monitor at the MOCA exhibition. James Nisbet e-mail to the author, August 2, 2012. ↩

- Hal Foster, “Introduction to Questionnaire on ‘The Contemporary,’” October 130 (Fall 2009): 3. ↩

- See, for example, Maura Coughlin, “Landed,” Art Journal 64, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 105, where she writes, “Boettger also writes a European presence back into the groundbreaking group shows.” See also John Beardsley’s Earthworks and Beyond: Contemporary Art in the Landscape (New York: Abbeville, 1998); and Jeffrey Kastner and Brian Wallis, Land and Environmental Art (1998; London: Phaidon, 2010). ↩

- Probing the Earth: Contemporary Land Projects was organized by John Beardsley for the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, and traveled to the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art and the Seattle Art Museum. ↩

- Dave Hickey, “Earthscapes, Landsworks, and Oz,” Art in America 59, no. 5 (September–October 1971): 48. I discuss similar issues in my book Earthworks, 207–25. ↩

- Charles Ginnever, in an unpublished interview by Suzaan Boettger, August 4, 1994. ↩

- For predecessors to this procedure, see Boettger, Earthworks, 83 and 270 n42. ↩

- Siegelaub was more expansive in an unpublished interview with me, December 10, 1994. In saying that the artists “looked around and made work from whatever they want to with what was already there,” Siegelaub mischaracterizes the artists’ deliberate interaction with local materials, which was planned in advance. For a detailed account of the exhibition, see Boettger, Earthworks, 80–84. ↩

- Boettger, Earthworks, 165. Regarding De Maria, Leavitt stated amiably, “It was a very fine piece, actually . . . made sense when you understood the context . . . it seemed to be also a gesture against art public and museum stodginess, and so on.” Leavitt, unpublished interview by Boettger, June 8, 1994. ↩

- Heizer, whom Kaiser and Kwon quote, is mistaken in attributing De Maria’s use of the term to 1967; it was 1968, regarding De Maria’s Munich Earth Room, AKA 50 M3 (1,600 Cubic Feet) Level Dirt/The Land Show: Pure Dirt/Pure Earth/Pure Land, at Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich, September 28–October 12, 1968. ↩