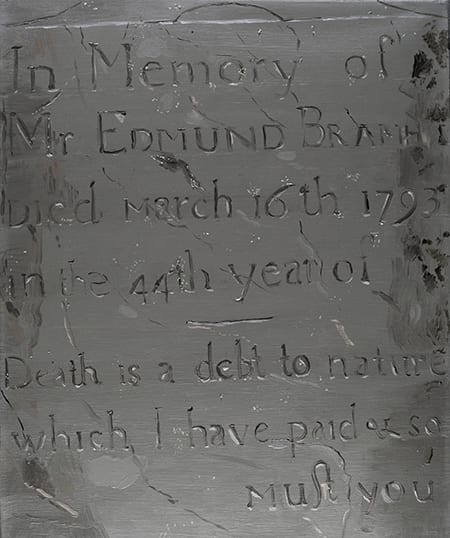

Josephine Halvorson, Wilmott 2, 2012, oil on linen, 46 x 27 in. (116.8 x 68.6 cm) (artwork and photograph © Josephine Halvorson)

Five gravestones—a family named Wilmott—are mounted side by side facing east in a cemetery south of London.1 Acid rain has eroded the words. Lichens, like Van Gogh blooms in orange and yellow, cling to the mauve stone. I try to pick out the letters with my eyes, but the text is slowly disappearing right in front of me. I make a painting of each stone to decipher the people beneath—trying to make legible their lexical identities through the oily, colored substance of my paint.

An awareness of death is what connects us to objects through our own sensate bodies, and an interrogation of objects mirrors our own mortality. Sensation and imagination defy the inevitable passage from life to death. In Memento Mori, my painting from 2008, the inscription from a Columbia County, New York, gravestone reads

Death is a debt to nature due

Which I have paid

And so must you.

The verse is a popular eighteenth-century epitaph on gravestones in the American Northeast. Regardless of the quote’s ubiquity, the first-person voice belongs specifically to Mr. Edmund Bramhall, who rests beneath the soil, beneath the stone. The expression, still palpable more than two centuries later, contradicts the mortal state of its speaker and the finality of the transaction of a debt paid.

If we were truly to see death as an end, then would we not bury someone without a monument to her or his existence? To mark a grave is to extend the life of the dead through the memory and imagination of the living. The Bramhall family evidently employed a carver to etch the stone, which for a period of time serves as a medium between the living and the dead. But once the memory of the deceased has itself died and the import of a burial is lost, the stone continues living. It becomes a body in itself, engaging an onlooker through its sensual and metaphorical qualities. When the look is returned and the acknowledgement made mutual, the inert stone is animated and the animate is aware of its own impending inertia.2 Reciprocal projections emanate outward, converging in the space of the imagination.

“Memento mori” has long been a theme at the heart of the still life genre. In my painting, however, I do not wish to assert moral injunctions such as warnings of earthly vanity through the pictorial. Memento Mori, though it might one day serve as my own epitaph, is not meant to continue the memorialization of Bramhall’s life.

Josephine Halvorson, Memento Mori, 2008, oil on linen, 17 x 14 in. (43.2 x 35.6 cm (artwork and photograph © Josephine Halvorson)

Through the medium of painting, I work at understanding something else in the world while affirming my own place within it. The ideal of this kind of Transcendental, interpretative labor is Henry David Thoreau’s account of the bean field.

As I drew a still fresher soil about the rows with my hoe, I disturbed the ashes of unchronicled nations who in primeval years lived under these heavens, and their small implements of war and hunting were brought to the light of this modern day. They lay mingled with other natural stones, some of which bore the marks of having been burned by Indian fires, and some by the sun, and also bits of pottery and glass brought hither by the recent cultivators of the soil. When my hoe tinkled against the stones, that music echoed to the woods and the sky, and was an accompaniment to my labor which yielded an instant and immeasurable crop. It was no longer beans that I hoed, nor I that hoed beans.3

Through the act of cultivating his crop of beans, which Pythagoreans had equated to souls, Thoreau physically encounters his predecessors: his hoe uncovers the evidence of their existence. It was not the faintly audible noise of nearby Concord, nor the sounds of the wind through the trees; it was the company around him, those who had worked or perished in that very field, whose voices were heard. Present and past, subject and object, converge. The crop was then, for a moment, beyond value.

But what if the unchronicled dead were neither willing nor able to offer their accompaniment? What if these Native Americans didn’t want their land to be disturbed by a breach of their peace, to be used as a bed to grow beans for the privilege of a white man’s experiment in self-sustenance and self-knowledge? Is there always disturbance in interpretive work? What if that music, as Thoreau puts it, is an unharmonious clamoring—or more problematical, if there is no sound at all?

The Shame machine, Tecopa, California, March 2011 (photograph © Josephine Halvorson)

These questions arose in my attempt to make a painting of a large diesel compressor next to a mine shaft on a ridge along the California-Nevada border. Its base showed the recent shine of a grinder, as if its ankles had been gnawed, its tendons sliced. It had been pushed on its side, an effort requiring considerable force, revealing the concrete foundation on which it had been secured for decades. Thousands of dried black insect carapaces were exposed in a dense layer. Looking at the machine askew, it was suddenly a severed head, its facade transformed into a face: a bolted plate resembled a shut eye, a dark recess became an open mouth, and a heavy steel shaft protruded, suggesting Pinocchio’s telescoping nose. On its rusted side, in white spray paint, someone had written “Shame.”

This was a painting I had to make. The compressor seemed to have so much to say, and not just through its parted lips. As I envisioned this mechanistic creature finding its way into my painting, a concatenation of other images appeared: Munch’s howling scream, Lee Lozano’s trembling hammer, Philip Guston’s ghostlike Klan members, and Arthur Dove’s mowing machine.

Arthur Dove, Mowing Machine, 1921, oil on canvas. The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York, Gift of Paul Rosenfeld (artwork © Estate of Arthur Dove; photograph provided by Lehman Loeb

Art Center)

Dove no doubt came to mind because of the painting I had made three days earlier of an earthy green valve from a disused steam-powered “donkey,” a massive machine used to extract lumber from the redwood forests of Mendocino County. Two days before that, when my plane landed in San Francisco from New York, the Tōhoku earthquake had thrust the ocean over Japan, and sent a shiver of panic through northern Californians. It was not the coastal road closures, or even a radioactive cloud heading my way, but rather the relentless rains that had driven me to the desert, to this “Shame” machine. Death Valley was the only place in the state of California where the air was dry.

I took Route 5 south for hundreds of miles, aware for the first time of the breadth of California’s irrigation and industry, where row after row of orchards recede in near-perfect perspective. I drove by the Bakersfield fruit processing plants where those very fruits are juiced and bottled. As night fell I discerned the distant light configurations within Edwards Air Force base. I spent the night in Barstow, the popular resting spot midway between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. And in the morning I forgot my cell phone charger when I left in a hurry after waking up next to a roach that was over an inch long. I arrived in the desert on Wednesday, March 16, 2011.

Tecopa, California, is a small town at the edge of Death Valley National Park. It is quiet, except for the wind. Residents in RVs slip under the radar of permanent addresses, finding refuge from the constant reach of cell phone reception and other imposing technologies. On the fringes of town I’ve seen couples in their seventies stroll naked through dry shrubs before disappearing into natural, healing hot springs. It’s easy to witness such events, as the earth is bare, no trees or buildings block the view, and your eyes can see miles into the distance. Its openness offers a sense of freedom.

Josephine Halvorson, Steam Donkey Valve, 2011, oil on linen, 18 x 23 in. (45.7 x 58.4 cm (artwork and photograph © Josephine Halvorson)

A fine dusting of snow on every surface was actually salt particles, which had been lured from the ground by a recent sprinkling of rain, only to be left behind when the water evaporated. The landscape was bright and desaturated.

Minerals seemed to make their way inside as well. The small cabin I rented at one of the two resorts in town provided a kitchenette and several aluminum pots and pans, which were thick with a coating of oil and mineral sediment. The water from the tap came out at a single warm temperature and tasted of salt and chalk. And there were outdoor hot springs in stucco buildings, each with a single light bulb and painted white and blue as if to suggest a Greek island.

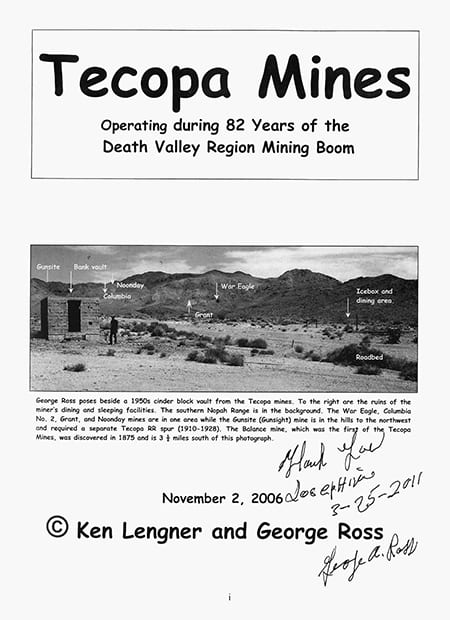

Tecopa is an oasis of sorts. I would have expected more infrastructure, and certainly more of a visible history, than I initially observed. The only commercial outfit in town, other than the resort office and a closed café, was an art gallery/bookshop where I bought a book called Tecopa Mines: Operating during 82 Years of the Death Valley Region Mining Boom.4

The surrounding mountains, once the bottom floor of the sea, show veins of minerals in profile. Their patterns up close are the same as far away: jagged, persistent, horizontal lines reappear in the graphic silhouettes of Southern Paiute baskets.5 It was in these mountains that mining camps were set up and, as indicated by the relatively recent photographs in the book, they were still accessible, though long out of commission. I was drawn to the parallels between mining and painting, of unearthing something beneath the surface through recognition and labor.5

Desert landscape, Tecopa, California, March 2011 (photograph © Josephine Halvorson)

If you follow the difficult terrain of the Old Spanish Trail, ten miles south of town off a dusty track is the Columbia No. 2 mine. To its west is a white pit, a talc depository still in operation. And off a side road through a ravine is a burgeoning date ranch, where several species of dates are cultivated, few of which are grown outside the Middle East. Approaching the mine, dark clusters tucked into bald hills come into view as wooden structures surrounding the entrances to shafts. For the final arduous mile, a mountainous climb up to the mine site, the threat of a flat tire is imminent. Strewn everywhere are rusted tin cans, flanges of corrugated steel shot through, pipes, and nails. Once the road levels off at the top, several shaft entrances are visible—a few within walking distance—and much mining debris remains: machine parts, scrap steel, and concrete foundations.

Only two hours due west from Las Vegas, this region has long lured mining engineers and capitalists hoping to strike it rich: the cross sections of hills and mountains reveal veins of metal oxide, irresistible to entrepreneurs in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and perhaps again to be seen as future resources. In some periods, these mines were among the world’s largest producers of lead and silver. In 1908 Nelson Z. Graves of Philadelphia bought the Tecopa Mines “not for the specific profit he could make from selling lead; but rather as a cheap source of lead for his paint company.”6 Today, cities such as New York are mandated to remove the paint that contains the lead Graves’s company extracted.

Ken Lengner and George Ross, Tecopa Mines: Operating during 82 Years of the Death Valley Region Mining Boom, 2006, title page with author’s inscription (page © Deep Enough Press, Shoshone, CA)

As an artist making work in relationship to environment, I was enticed by the idea of painting the very landscape from which my paint, the lead primer on my canvas for instance, could have derived. The Impressionists painted the landscape as it changed with modernity—with the very products of new industries. Michael Taussig writes, “Yet the very same chemical revolution of the nineteenth century that emerged from the search for color and drugs from coal tar, this very same chemical revolution polluted those broad strokes of remaining nature with new texture. The sunsets never looked so stunning as they did through the haze of factory smoke and soot.”7

March 25, 2011, was dry and clear. The weather forecast said winds would exceed thirty miles per hour, and they did. I set up my easel in front of Shame. Trying to be unobtrusive and respectful, I found myself listening to the psychic, historical, and art-historical chatter around me. Occasionally the open desert distances made me feel someone was watching me from far away, and I would abruptly stand still and peer out through the miles of clear air in front of me, combing the terrain with my eyes.

As I was setting up my materials, the twenty-nine-by-thirty-nine-inch canvas that I’d clamped to a wooden box easel became a sail and the whole apparatus swiftly came crashing down. Two legs of the easel snapped against the concrete, their splinters adding to the debris. Trying not to panic, I rescued the canvas and fumbled with the easel. I dragged a three-by-seven-foot sheet of corrugated steel over and tried to lean it against the compressor as a windshield. I scoured the ground to see if I could effectively back my vehicle up to provide shelter but there were too many obstacles. My skin was feeling sunburned. And I hadn’t even started painting.

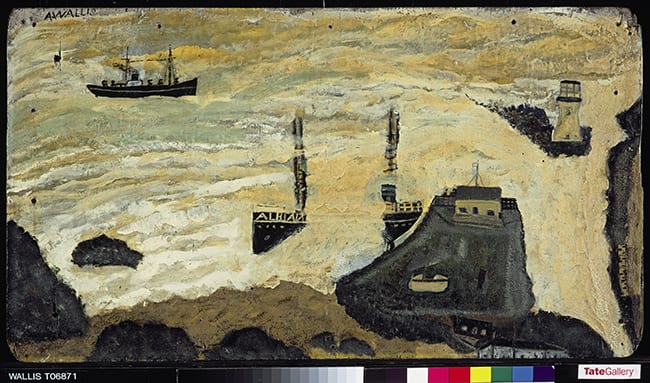

I now know I should have taken greater precaution. Through the grapevine of plein-air painters, I have since learned that one must always screw eyehooks into the back of the wooden stretcher, anchoring it to the ground with fishing wire. I learned this a year too late. Regardless of my more casual approach, there was a brutality to the way my easel was struck down that intimated a relationship between the subject and the materials. It was unsettling. It was as if, in an Alfred Wallis painting, the sea suddenly surged, dissolving its own surface, drowning the support, wiping away the very scene it inspired.

Alfred Wallis, Wreck of the Alba, ca. 1938–39, oil on wood, 14⅞ x 26⅞ in. (37.7 x 68.3 cm). Tate Gallery, London (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by Tate London/Art Resource, NY)

I consoled myself with the thought that I would return for Shame. It would have to be after the heat of the desert summer. In the meantime I wanted to make something from my investment in the mine—not necessarily to justify the time and expense of travel, but more importantly to explore my curiosity about the site and my almost magnetic attraction to it. I found a way to work out of the back of the Ford, backing up as close as I could, and made this painting, Mine Site. It looks like a conventional still life: a tabletop with quotidian objects, which tell the story of their environment. A nail, a rock, a pebble, and several bits of iron sit on the surface of a concrete block. But I did not arrange them, or even touch them. As Norman Bryson might say, the scene presented no syntax.8 It fell squarely within the Greek genre of rhyparography, the depiction of odds and ends, of debris. Like Herakleitos’s mosaic of the unswept floor, these were the remnants of industrial extraction.

After locking horns with Shame, I found relief in not knowing what lay before me. The only question that came to mind was an empirical one: how did these pieces end up and remain a foot off the ground on the top of this plinth? Surely the wind couldn’t have lifted them, as it would have blown them off as well. The scene suggested a party where the guests suddenly departed.

Josephine Halvorson, Mine Site in situ, 2011, oil on linen, 29 x 39 in. (73.7 x 99 cm (artwork and photograph © Josephine Halvorson)

I was not just depicting odds and ends, I was surrounded by them. Hours into the painting I realized I was standing on a can opener, intact, perhaps one which had sliced the tops off many of the cans I saw on the rocky road to the mine site. The ground was littered with thousands of these rusted shards, once shiny, trucked in over the course of decades to this largely forgotten American landscape, and never cleaned up.

After I left Tecopa, the urgency to paint Shame only intensified. I had more time to reflect on its possible allusions. Why was the S capitalized? Was it a proper noun? Did the word signify a moral judgment? And if so, was it on the mine’s active phase or its closure in the 1960s? Did it refer to our current economic depression, to the outsourcing of mining to China, Australia, and Peru?

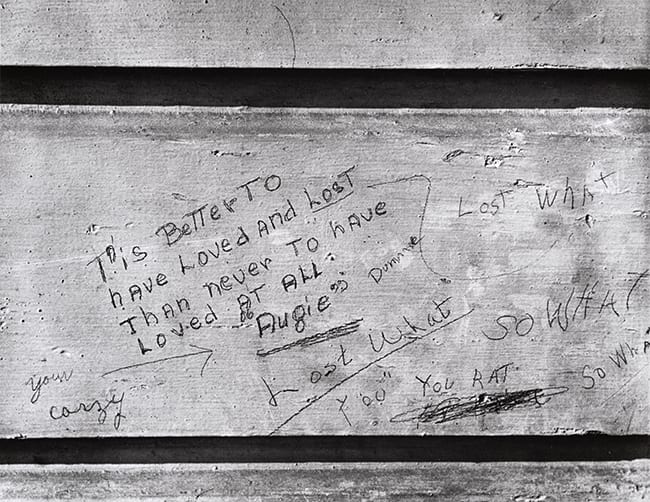

The way the word was painted brought to mind the mystery of the legible in Dana Frankfort’s paintings of words. But as I became less certain of its meaning—and its author—I felt more perplexity than wonder at not comprehending the context for this expression, this defacement. I was reminded of the distance between voyeur and auteur in John Gutmann’s photographs of American graffiti, especially his 1938 black-and-white photograph Lost What, in which the face of a slatted wall is etched in graphite with a conversation that roves across its surface:

Herakleitos, detail of The Unswept Floor, 2nd century BCE, mosaic variant of 2nd-century BCE painting by Sosos of Pergamon. Museo Gregoriano Profano, Vatican Museums (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by Scala/Art Resource, NY)

T’is Better To

have Loved And Lost

Than never To have

Loved At ALL

“Augie”

Dummie

Lost What

your crazy

You

You RAT

Lost What

So WHAT

So Wh . . .9

The central adage comes from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s In Memoriam A. H. H., a poem dedicated to a dear friend who passed away suddenly. Its message is widely interpreted as a comfort to those suffering the grief of losing a loved one. Yet in Gutmann’s photograph from eighty-nine years later, the banter appears, at least initially, unsympathetic. The way each word is written emphasizes its tone: while the excerpt is carefully written and twice inscribed, the responses are scrawled quickly, a sharp and fast line scrapes under the retort, “Lost What.”

Dana Frankfort, Crack, 2007, oil on panel,

36 x 48 in. (91.4 x 122 cm) (artwork and photograph © Dana Frankfort)

But what if “Lost What” is actually an inquiry? What if “So What” is a moral dismissal of the drama of death, a sympathetic nudge toward recovery? Did the original writer return to this wall? Perhaps he or she didn’t even write from experience, as we might assume. How much can we infer from inscriptions on walls? Does anonymity encourage or discourage sincerity? I think about this when staring at graffiti in a public restroom, or passing by a tagged building, but especially in regard to painting, both literally and metaphorically. If painting can be seen as material decisions made on a surface, is it not an inscription too? My inscription of “Shame” could put me in the shoes of the person who wrote it and bring me closer to understanding the original impetus. My painting, an inscription itself, could then continue the conversation on the walls of a gallery, in New York, for example.

It was with this in mind that I returned to Tecopa in early October 2011 with both enthusiasm and nervous anticipation.

I’m told to this day by my travel companion that it was on the final mile approach to the mine that I expressed a clear premonition that the diesel compressor with its dumb lexical designation would no longer be there. Risking flat tires past the piles of rusted tin cans, flanges of corrugated steel shot through, pipes, and nails everywhere, we arrived at the top, where the road levels off and several shaft entrances are visible. Much mining debris remained: machine parts, scrap steel, concrete foundations—but the diesel compressor was gone. A broken two-by-six, resting on thousands of dried black insect carapaces, suggested the final levering of a ton of metal onto the back of a truck.

John Gutmann, Lost What, 1938, black-and-white photograph, San Francisco. Collection Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, AZ (photograph © 1998 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents)

I told my companion to leave me alone. I was disconsolate, angry, pacing. I was shocked that it was gone, but more disturbed by my own premonition. Was the word “Shame” actually addressed to me, as if the machine itself predicted my own missed opportunity to paint it?

Where was the machine? I found myself calling out to it like the young boy in the 1953 American Western Shane as he watched his own image of hope and a stable future disappear into the desert.10 The S, afterall, had been capitalized. It was perhaps the machine’s name. The feeling of abandonment might have been mutual in that I was responsible for its loss through my own acquiescence to the elements in March: if only I had persevered, “Shame” could have had another chance in my painting.

Registering my earlier observations of fresh hacksaw marks only made me more disappointed in myself for not noticing previous attempts to unmoor the machine from its foundation. My painting Mine Site now had new meaning: I had painted the loss of another machine without even knowing it.

The compressor had been seen as scrap and was on its way to be melted down, if it hadn’t been already. I now understood that “Shame” referred to either the possibility—or impossibility—of stealing this vast piece of steel for cash. In either case, I hadn’t been sharp enough to play out this scenario. I was overly invested in the historicity of the object, not its present value.

Columbia 2 mine site with Shame, Tecopa, California, March 2011 (photograph © Josephine Halvorson)

I made a rapid estimation that the value of the object for scrap was worth significantly less than my painting of it might have been. If only I could have negotiated with the thieves, I would have happily paid them to keep the object in situ, and then claim the payoff as a tax deduction. Two different markets reached thousands of miles, competing in this one spot on the hills between Nevada and California. Scrap metal prices had won. I was a sore loser.

Later, when relating this story to my parents, my father consoled me by saying that the compressor might not have wanted to be painted. “Perhaps the machine had blood on its hands,” he suggested. It had, after all, provided the power to operate heavy machinery, such as pneumatic rock drills hundreds of yards beneath the shaft entrance.

On further reflection, the entire site had been about metal extraction. The diesel compressor was back in the circulation of global capital. I had missed my transcendental moment.

Since the recycling of “Shame” and the disappointment that ensued, I’ve found myself working in series and returning with greater insistence to my chosen site. Moreover, I see painting as a place to acknowledge the time revealed by objects that are in the process of disappearing, where legibility is more subject to erasure, and erasure more subject to legibility.

“Shame” was too ineffable to exist in a painting. It would have overwhelmed. Only when it disappeared could I make something of it.

Josephine Halvorson is an artist based in Brooklyn and Canaan, New York. She works on site, collaborating with the environment to forge a painting that serves as a record of time. Halvorson’s work has been exhibited internationally and is represented by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, and Galerie Nelson-Freeman, Paris. She is the recipient of many grants and awards, including a US Fulbright Fellowship to Vienna and a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Grant. She teaches painting at Princeton University and is a critic in the MFA program at Yale University.

This essay originally appeared in the Winter 2012 issue of Art Journal.

- Iain Sinclair writes about Shoreham, Kent, the site of the cemetery, in his 2002 psychogeography of the suburbs of London: “It comes as a shock to find Shoreham where it is, so close to London. . . . Shoreham is still a removed place, a cleft between close hills. We felt its shadowy, covert nature—dark cottages, tangled orchards; it was damp, folded in on itself and its history. . . . A sudden turn, a drop in the road, and out of nowhere we’re up against the church and the river.” The nineteenth-century painter Samuel Palmer lived within two hundred yards of the cemetery, making drawings, notes, and paintings in what he called the Valley of Visions in an effort to “bring up a mystic glimmer.” Sinclair, London Orbital (London: Penguin, 2002), 413–15. ↩

- Alexander Nemerov approaches Raphaelle Peale’s 1813 painting Blackberries through the language of phenomenology: “We project our bodies into a world they make palpable; in this world our bodies ‘adhere,’ sticking as it were to the surface of things, and thus reversibly give back to us a sense of our own embodiment.” He continues, “For Merleau-Ponty, if the observer’s body makes the world palpable, the palpable world reciprocally materializes that very body.” Nemerov, The Body of Raphaelle Peale: Still Life and Selfhood, 1812–1824 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001), 32. ↩

- Henry David Thoreau, Walden, ed. Jeffrey S. Cramer (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), 153–54. ↩

- Kenneth Lengner and George Ross, Tecopa Mines: Operating during 82 Years of the Death Valley Region Mining Boom (Shoshone, CA: Deep Enough Press, 2006). ↩

- Robert Smithson writes about the relationship between art and mining in 1972, “A dialectic between mining and land reclamation must be developed. Such devastated places as strip mines could be re-cycled in terms of earth art. The artist and the miner must become conscious of themselves as natural agents. When the miner loses consciousness of what he is doing through the abstractions of technology he cannot cope with his own inherent nature or external nature. Art can become a physical resource that mediates between the ecologist and the industrialist.” Robert Smithson, The Writings of Robert Smithson, ed. Nancy Holt (New York: New York University Press, 1979), 220. ↩

- Lengner and Ross, 43. ↩

- Michael Taussig, What Color Is the Sacred (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 43. ↩

- “Trompe l’oeil pretends that objects have not been pre-arranged into a composition destined for the human eye: vision does not find the objects decked out and waiting, but stumbles into them as though accidentally. Thrown together as if by chance, the objectives lack syntax: no coherent purpose brings them together in the place we find them. Things present themselves as outside the orbit of human awareness, as unorganized by human attention, or as abandoned by human attention, or as endlessly awaiting it.” Norman Bryson, Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting (1990; London: Reaktion, 2004), 140. ↩

- Max Kozloff, The Restless Decade: John Gutmann’s Photographs of the Thirties, ed. Lew Thomas (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1984). ↩

- Shane, dir. George Stevens, color film, 118 min. (Paramount, 1953). ↩