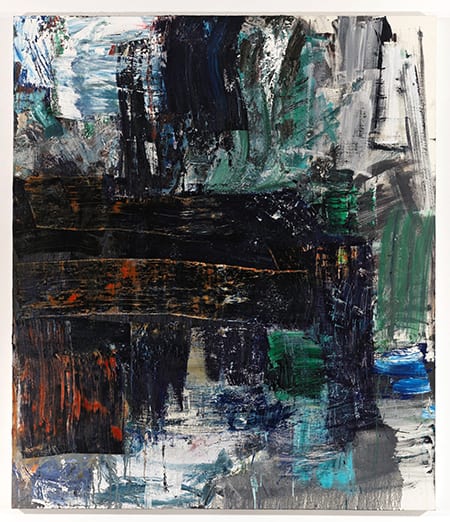

Louise Fishman, Zero at the Bone, 2010, oil on linen, 70 x 60 in. (177.8 x 152.4 cm). Private collection (artwork © Louise Fishman; photograph provided by Cheim and Read, New York)

Carrie Moyer: Can you give me a little background on your new paintings?

Louise Fishman: This all came to me in the last couple of weeks. In the late 1980s, early 1990s, my partner and I had gone to Madrid to see the big Velázquez retrospective. I’d never been to the Prado. I spent a lot of time looking at the Velázquez and wandering around the museum. Eventually I found Goya’s Black Paintings. I’d only seen poor reproductions. They had recently been cleaned and were in their splendor. They knocked me out. I spent a lot time studying them and wandering around Madrid. It wasn’t a long trip, but it was very dense. When we came back, I started working on a number of things—I was about to have a show. I was living in the country then, and my studio was in a firehouse. I worked on a painting that was 90 by 110 inches, the same size as Kaddish, which had been painted several years before, after a trip to Auschwitz.

I went up to the country and began painting. I’d finished a lot of work for this show and I’d moved it upstairs in the firehouse, which was where the storage area was. I was working primarily on the second 90-by-110-inch painting for about three months, over and over again. When I finished it, I realized that it was the way I’d been digesting the Black Paintings. I remember it having an odd surface; I felt it was one of my best paintings. I had to go up to Vermont to teach for ten days right after that. While I was up there, I got a phone call from Betsy [Crowell] saying, “There’s been a small fire in your studio, and I think you should come home.”

I thought, a small fire? Why is she calling me if it’s a small fire? So I went back and, to make a long story short, the studio was destroyed. I arrived and went right to the firehouse. Outside were my friends: Amy Snider was there, maybe Jenny Snider, Betsy, people from New York and local friends. They didn’t know where the fire started, and it wasn’t reported in time. The locals had taken the paintings I’d stored upstairs and laid them out on the lawn across the street from the firehouse. So those paintings were smoke-damaged but safe.

Everyone was waiting for me to walk into the studio. I’d never seen anything like it. Black and smoky. Everything had exploded. The paint cans had shot across the space, so there were paths of paint in all sorts of color. In the middle of the studio the large painting had exploded too. It hadn’t even been photographed yet. The braces from the back of the painting had flown into the room, and in the middle of the studio was a charred, black cross. All the things you keep in your studio were destroyed too—my brushes, my knives. I just couldn’t believe what had happened. I was angry, devastated. I got very sick with chronic fatigue syndrome, which I had for several years. I was a basket case for a long time. I never thought about that painting again, and I never thought about Goya’s Black Paintings.

Moyer: The whole event is so laden with symbolism—it’s almost unbearable. Between the cross, the smoke, the fire, the ashes . . .

Fishman: It was horrible. I lost everything; I’d lost my life. All my slides melted. A lot of blank paper was damaged, and the smoke had curled up the side of the paper. I used it later for drawing and painting, once I’d had a little distance. One of the things I hadn’t used was a little canvas-covered sketchbook. Smoke on

the cover and inside. And I sat down with a few objects that survived: a rock

from Auschwitz, a whittled rabbit that a local guy had made. . . . Everything was

covered with a lot of green paint. Two little figures that Betsy made for me out of clay and one piece of sculpture that my friend Brandt Junceau had made. I was hardly functioning. All I could do was open the book and trace each object. Very slowly I started doing some drawings, rubbings and transfers. The drawings were not direct. A lot of pages at the end were empty. It was a book about the fire by a person who had been through it.

Moyer: Also it was a kind of archaeology. Because the stuff that was left was not painting. It was little fetish objects.

Fishman: Yes, things that I treasured. Each one of them had been transformed. They had paint on them, or the clay was darkened as if it had been in a kiln again. Then we went out to New Mexico. I couldn’t drive; I had to sleep all the time. So we went in a van, and we had somebody build a bed in the back of the van. We rented Harmony [Hammond]’s place in Galisteo. Then I met Agnes [Martin], which started a very important series of events.

Moyer: I spent the last couple of days reading a lot of your press, and there are many citations of “a return to the grid” in the early 1990s. The grid meets gesture to create structure. Does this meeting with Agnes have any bearing on this?

Fishman: Yes, it had a lot to do with it. She showed me paintings in her studio after we got to know each other, and then she started showing me drawings. I’d always loved her work and was fascinated by her. I was really beside myself just being around her. When I first saw her, she was sitting in her rocking chair, not saying much. And I thought, It’s like sitting with the Buddha. So I’ll just meditate. That’s what she seems to be doing. [Laughter.] As I was looking at her drawings,

I suddenly realized her work process was a meditation. And I thought, Oh I know that. I’d had a history of meditation and I still do. So two or three months later when I returned home to the country, I got these little Japanese foldout books and started working with these little grids. I would just make things out of a meditative state instead of wherever else my work comes from. So that’s where the grid started.

Moyer: But you were using the grid a lot in the unstretched works?

Fishman: And I was using it in the 1960s.

Moyer: What did your work look like in the late 1960s?

Fishman: Before the women’s movement? I was doing hard-edged grid paintings. What had interested me the most were Sol LeWitt’s three-dimensional grids. First I was doing big, hard-edged shapes.

Moyer: So you were taping?

Fishman: Oh yeah. And then I did the grids where there was an intersection between a vertical and a horizontal. And there was a little square and the color change. They were arbitrary colors. And I did a bunch of those.

Moyer: Were you using oil paint or industrial paint?

Fishman: No, I was using acrylic. Then I started doing stain paintings.

Moyer: You were so in the moment!

Fishman: They were grids but there was a little more flexibility in them because I didn’t control the paint the way I had. They were still taped but the paint would go under the tape. I may have been pouring more—but they were still grids. That’s what I was doing when I got involved with the movement. I was in my women artists group. That’s when I made the decision not to do any of that work anymore. I decided I wouldn’t do anything that I didn’t want to do. In other words, to try to figure out what part of me came from all the male stuff in my history and to eliminate it—just to see who I was without all that. Impossible,

of course.

Moyer: Yeah, how could you even do that? How did it work at the time?

Fishman: Well you can’t. But you know what it is. It’s kind of a structure that you build, something that you set up, almost like an armature.

Moyer: Oh you mean modernism? [Laughter.] That’s one of the armatures . . .

Fishman: Yes, but it was more like I wanted to have every choice open to me. And if I never painted again, fine.

Moyer: Whoa, really?

Fishman: I thought a lot and started making things out of canvas. Cutting up the grids and stitching them together. Dying canvas in the sink. I didn’t work in a studio anymore; I worked in my living room and was living with Esther [Newton]. I decided to stitch—which I hated. [Laughter.] I spent my life avoiding sewing and anything else that had to do with “women’s tasks.” I thought, Okay I’m going to embrace this shit. I hate it, but I’m going to figure out what it is. I’m going to figure out what it is in me that has such trouble with this.

Moyer: Did you make the connection to the fact that most of the women in your consciousness-raising group were straight? These were the activities that lesbians were trying to escape in the 1950s, by playing basketball, etc. Suddenly they become this kind of relevant art-making model with the advent of feminist art movement. Was it falsely relevant? It feels like something that got laid over your studio practice. Something you were trying on, perhaps . . .

Fishman: When I was in grade school my friends all decided they wanted to learn how to knit and crochet. And I went with them, even though I didn’t want to do it. Knit one, purl two. I thought, I hate this, but I tried. I made an apron for my mother, in Home Ec, a yellow apron.

Moyer: When were you were working on unstretched canvas? You went back to stretchers in 1977?

Fishman: No, 1978–79. Right before that I had been doing paper pieces. I did cutout plywood paintings for my first solo show in New York. They got very good press, and all these artists were coming up to me, famous artists like Ron Gorchov.

Moyer: Was this before you were in the Whitney Biennial? Before 1973?

Fishman: No. In 1973 I was doing calligraphic paintings, writing on unstretched canvas. I was trying to mimic my friends, who were all writers. I was trying to make a language. Some of them tended to be like cartoon blocks but with just drawing inside. And I had a little system about how I would construct them; each one was divided into segments. I’m not nuts about that group. Except for the one that was in the Whitney Biennial that I like a lot.

Moyer: I was recently looking at Pat Steir’s drawings from that period, and I’m interested in this relationship between language and abstraction.

Fishman: Pat used literal words, like Joan Snyder did.

Moyer: Can you just talk a little about that? I mean using words in painting has been a massive taboo for a long, long time. If the painting is good enough, why does it need text? They would seem to negate each other. It’s interesting to me at that moment (late 1960s) there are all these women artists thinking about text, language, and the language of painting.

Fishman: I don’t think I was in that group actually. My interest came solely from the fact that all my friends were writers, anthropologists, and other kinds of academics. They formed writing groups. And I couldn’t be in that writing group. My work had no connection to any of the politics. In the late 1960s and early 1970s

I did my painting; nobody knew about it but my friends. I had gotten involved with Redstockings when I met Esther, and she was very radical. Eventually the strict consciousness-raising groups morphed into new groups based on specific interests that people had such as writing, especially journal writing. Jill Johnston, Bertha Harris, Esther, and others who were getting published and rethinking how they were putting their work together. This was really interesting to me. And yet

I felt so excluded that I started making marks—as if I were drawing fake writing. In retrospect, I’ve always had an interest in calligraphy starting with Hebrew, a language that I didn’t understand. Something always upset me about it. In fact, when I was in art school, we used to sit in Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia and sketch people all the time. Once there was a Yiddish newspaper lying next

to me, and I picked it up and pretended to read it. I was eighteen. I desperately wanted to know what it was. It was supposed to be my language, but I’d never been taught it. I knew a little Yiddish, but hardly any. My parents used it as their secret language: “What’s for dessert?” In Yiddish, “Nothing.” [Laughter.]

Moyer: Your parents were secular?

Fishman: My father grew up as a very orthodox Jew. His father was a Talmudic scholar. My father taught yeshiva boys how to read, do their work, and say their mofters. His father died when he was about fifteen. I found out that he stopped believing in God when his father was taken from him. He said, “What kind of a God would do that to a child?” I said, “You don’t believe in God, Daddy?” We had gone to shul regularly all through my childhood. But then he stopped after we were grown. And he said, “Yeah, I don’t believe in God, but I talk to him sometimes.”

Moyer: It seems like your generation in particular is in this position where you constantly had to parse out different bits of identity. Do they ever get integrated?

I was looking over your CV, and when you were sixty, you were still being put in shows for emerging women artists. When is it that you will stop “becoming” these three different kinds of artist—abstract, feminist, Jewish?

Fishman: It’s awful, I hate it. They are all kinds of links, and they need to be made. Before I made the calligraphic paintings, I was doing these stitched grids. They were more like drawing and became a kind of language. With the exception of the first two years in art school, I have never done anything but abstract work. It never interested me.

Moyer: You went to graduate school—something that was fairly unusual for the mid-1960s.

Fishman: I went from 1963 to 1965. I was a senior at Tyler. And my teacher suggested during our final review that I go to grad school. I said, “Graduate school in painting? What are you talking about?” I thought it was bad enough that I had to go to art school because I didn’t feel like I learned dick. I didn’t learn very much, actually. I went to the University of Illinois.

Moyer: Were you exposed to what was going on in New York at the time?

Fishman: Oh yes. We looked at all the magazines. And then there was Chicago. I went to a show that Al Held had the Art Institute of Chicago—the first paintings I’d seen that were hard-edged. We were looking at Noland, Judd, and a lot of sculptors. It made me think about what I was doing, which was freely drawn, very organic, and very odd.

Moyer: Were you aware that you wanted to paint abstractly?

Fishman: Yes, I’ve known it from the first time I studied art. The [Philadelphia] Museum School was very advanced. Franz Kline had taught there. People there were involved in an “abstractionist” style. I was very involved with Kline and Guston, whose work I’d seen in magazines. I was already on a tear and very committed to that way of working and learning. Although that’s not what I was actually doing at that time, it’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to be on that path.

Moyer: Your relationship to abstraction takes a lot from that period. There’s no metatext going on. Everything in your work is coming from the experiential. It’s not painting about painting.

Fishman: No, no. Not at all.

Moyer: One could think of Abstract Expressionism as being a kind of postwar, Jewish identity art. A lot of the practitioners were Jewish. And it has a specific kind of secular, transcendental spirituality, even as it is claimed as a quintessential American art form. Do you think there’s a relationship between abstraction and your own background?

Fishman: The reason I got involved with it had nothing to do with anything but the freedom and athleticism of it, the power of it—like building bridges. Kline. Architecture has always come in and out of my work. It has to do with the grid and the sense of the window, interiors. Something that showed up a lot in abstraction during that time.

Moyer: De Kooning? Door to the River?

Fishman: De Kooning was my big hero. As well as Joan Mitchell. There were a lot of different strains that interested me. And Guston, who was just working with the mark. I didn’t really think about any connections other than the physical one. I’m sure I read stuff. But people didn’t talk about being Jewish then. I think that by osmosis there’s clearly a connection. For example, the idea of not painting

the human form, it being against Jewish law. I’m not even sure I knew that at the time. There’s a lot that enters your body without having direct knowledge. I’m very intuitive, and I’m absorbing stuff all the time.

Moyer: Were your mother and aunt reading publications like Art News during

the 1950s?

Fishman: My aunt was a big member of the art world in Philadelphia. She had a lot of shows and was very well known for a long time. My mother wasn’t showing. My aunt and Jackson Pollock had studied with Siqueiros during the legendary summer that he was in New York. She had a lot to say about Pollock. She didn’t believe in abstraction. I kept my mouth shut because she lectured to me and I didn’t want to get in trouble. She’d say, “Siqueiros was the first one to use enamel paint, and Pollock gets all the credit. His paintings are terrible.” She was terrifically well educated on her own. She never even went to high school and was completely self-taught.

Moyer: What kind of paintings did she make? Representational?

Fishman: Yes, but they had an abstract quality to them. A lot of Jewish-themed paintings. One beautiful painting shown in the Jewish Museum was of a shabbos meal. She was broadly knowledgeable about art, literature, and music. She and her husband were intellectuals. My mother had a subscription to Art News. She and my father got a membership to MoMA, and they used to send you free books with a membership. So she had a big library, and I was always in there looking. I would leaf through her books, but I didn’t really think of being an artist.

Moyer: This was in the early 1950s?

Fishman: Once I got to art school in 1956, I really started to look. That whole series The Artist Paints a Picture was so interesting to me because you could see the artist’s studio and what the artist looked like. And to me Joan Mitchell looked like a tough broad, like a dyke. I had just come out myself. And I thought, Oh look at her! I’d go to New York by myself and go to the galleries on Fifty-seventh Street. And I made a lot of decisions doing that. I remember thinking about how some of those painters copped out. They’d get to a certain point, and they’d start imitating themselves.

Moyer: Who are you thinking of in particular?

Fishman: Motherwell, for one. But there were plenty of others. I was set on being able to reinvent myself and to not fall into that trap. Because it seemed like death for an artist. I was way too high and mighty. I was like my father’s family: very rigid, very moral to a disastrous degree. No room for “human-ness,” mistakes, and any of the rest.

Moyer: And you applied some of that judgment to your development as an artist?

Fishman: I think so. I really have been consistent about not repeating myself. Lots of artists make a group of paintings that belong to a theme, and the paintings don’t vary that much. I never could do that. Because it didn’t interest me, and because I had a self-imposed restriction on never doing that. I’ve wondered about it. On the one hand, you could expand by going more deeply into something. But there are different kinds of expansiveness.

Moyer: I’ve been thinking a lot about women artists from the 1980s such as Sherrie Levine and Barbara Kruger. I just wrote a review of the recent show at the Neuberger Museum, The Deconstructive Impulse, which focused on women artists and postmodernism.1 For women artists in the second half of the twentieth century, if your work didn’t undergo these radical transformations, then you might as well have been dead. By virtue of who you were, you acted as a nexus of social change. Women were gaining entrée into the art world, something that hadn’t been possible before—however few were let in. It was almost mandatory that you constantly redefine yourself as culture moved forward. How could you not change?

Fishman: Yes. In the late 1960 and early 1970s, there were a lot of departures for me, especially in terms of the materials I used. When I finally went back to the stretched canvases, I had made a complete commitment to painting. I arrived at

a completely original thing after having gone through all these permutations. When I was in Chicago, I’d made paintings on paper because they didn’t provide me with a studio. I had a living room. So I couldn’t do the cut-wood pieces that

I planned to do. Initially I thought of them as drawings for cut-wood pieces, and that I would go the next step and make them more sculptural. That’s not what happened. Instead, the work became more painterly. I got to a point where the paper was too thin, too flat against the wall. I wanted something that projected outwards. And I thought: a canvas. [Laughter.]

Moyer: Voilà!

Fishman: Yeah. I thought, Oh this is exactly what I need. And I went back with

a vengeance.

Moyer: Thinking about your return to formalist abstraction, what kind of

reaction were you getting to it in the 1980s, the heyday of postmodernism? Everything that’s valued in the rubric of your work is being questioned in that moment. Especially with regard to whether the gesture can have a kind of authenticity.

Fishman: When I went to graduate school, it occurred to me that the gesture

is no longer relevant. I’m going to have to figure out how to do without it. That had been my entire connection to painting. So I started doing the hard-edged pieces. I also have a very strong connection to sculpture. And Minimalist work was very exciting to me. The more I educated myself about it, the more interesting it became. So I actually moved into a way of working that I never would have.

Who’s that guy that showed at Paula Cooper who numbered every piece he made?

Moyer: Jonathan Borofsky.

Fishman: I met him at a party in 1969, which was downstairs from where I lived on Cooper Square. He came up to my studio to look at my work and said, “This is the only kind of painting that can be made now.”

Moyer: Really? Jonathan Borosky said that?

Fishman: He said, “Painting is dead but what you’re doing is relevant.” They were the flat grid paintings. But in the 1980s, I was just trying to figure out how to paint again after having gone through a long period of questioning everything. I had attention from some quarters for a brief period. During the heyday of Baskerville-Watson Gallery, I was getting reviewed, and they sold all my paintings.

I was in the Whitney Biennial again and the Corcoran Biennial. In the 1987 Whitney Biennial, I had a room of paintings next to de Kooning’s room of paintings.

Moyer: You thought you’d died and gone to heaven!

Fishman: I want to go back to the beginning of the conversation and talk about the current work. Now you have all this background, including the information about the fire.

Recently my paintings haven’t had much black in them. A very important painting went down to the Basel Art Fair; there was a lot of interest in it. My dealer said it could have sold ten times over. And of course they want me to keep doing the same painting—something I can never do. And I came back to the studio, and the first thing I made was a black painting. It had nothing to do with anything I’d been thinking about, and I had no idea where it came from. It was a small vertical.

A friend e-mailed me from Madrid and said, I’m on my way to the Prado.” And I wrote jokingly, “Bring me back a couple of Black Paintings.” She said, “I’ll bring you the Dog,” and I said, “Great that’s my favorite painting.“ And I was walking over to meet Simon Watson, who knows the history of my work. I got to the studio and said to him, “I think the theme of my next show is going to be the Black Paintings. He said, “Great.” I thought, what does that mean? While we were talking I suddenly remembered the history of the studio fire. It all came back to me. And I thought, this is a natural thing for me to be doing at this moment. The fire is really behind me and this black painting emerged. It’s time to look at those paintings again and think about them. So that’s what I’ve been doing.

Moyer: It’s not a kind of elegiac gesture? Black paintings as a kind of summation of the things you’ve done in the studio?

Fishman: It’s something that popped up in the studio, but it wasn’t a theme per se. But the more I thought about it, the more it seemed like an appropriate move. When I brought the Goya book out, it was covered with smoke. The whole event just came rushing back.

Moyer: Now when you say “black painting,” are you using the term in an open-ended way? Is Yes a “black painting”?

Fishman: It’s really not about all of them being black, although black is involved. It’s really about some connection to those paintings of Goya’s.

Moyer: And that time in your life?

Fishman: That moment, and maybe even the painting that burned and was forgotten. In a way, I almost feel like honoring that painting.

Moyer: A kaddish for the death of a painting.

Fishman: Yeah, right. [Laughter.] I’m not sure where it’s taking me, but I see that it’s loaded. [Pointing to a new painting:] I’m looking at that and wondering where the color comes from. It really is a charred gray.

Moyer: Since we’re talking about black and the idea of black, maybe we could talk some more about your sense of color. On the one hand, some of them feel like an abstract version of a Social Realist painting. Gritty spaces where the light feels almost dirty. Very urban.

Fishman: Its funny that you should say that because my aunt, Razel Kapustin, studied with Siqueiros and did Social Realism. That’s what I grew up looking

at. My mother, Gertrude Fisher-Fishman, was doing post-Matisse and Cézanne-type paintings.

Moyer: So she was a more chromatic painter?

Fishman: She was studying at the Barnes Foundation, and looking at Cézannes,

a lot of Renoirs, too, and Matisse.

Moyer: Is your palette a kind of reaction then? Unconscious? Looking at the

catalogue you produced of your mother’s work, her colors are very vibrant and luscious.2 Filled with light.

Fishman: She was a real colorist. For me, one of my main interests has been using the paint as a part of the earth. Using it as a substance that’s raw. Where the whole marking system and color is a material. Which is why sometimes I can’t use much color. Color appears here and there, but it doesn’t feel like it’s an actual substance. It doesn’t have the kind of physicality that I need in a particular painting. At other times color comes up, and I associate it with a physical, natural resource rather than all the attributes (hue, value, etc.). I pay attention to them

of course. But I choose them for their material presence.

Moyer: When did you go back to painting with oils?

Fishman: About 1977, maybe a little later.

Moyer: I wonder about that because acrylics were made to be eye-popping. They were all about a demonstration of modern chemistry. It’s interesting to return

to a kind of elemental color that is made of minerals and earth. How do you include cadmiums?

Fishman: Cadmium would often be muted by something else. It gets really

interesting when mixed with black, for instance. When I went back to painting again, even before I went back to stretched linen, I wanted to use the materials

I had learned to use in art school. I learned how to grind my own paint. I had a real passion for making paint, noticing the difference between one pigment and another because of the way it absorbs oil, the different textures as you grind it. It was very physical, and that’s what appealed to me. I thought of it as the tradition of painting, but actually it was the physicality that I liked.

Moyer: I’m thinking about different paint technologies and how they mark time. One thinks of the earth colors and the umbers belonging to a particular period of painting. Oil paint is only used to make paintings, nothing else. Unlike acrylic, which bridges fine art and industry. Even though all of these paint technologies coexist now, they each bring with them a slice of history.

Back to the notion of how identity plays out in abstraction. It’s one of the ideas I’m endlessly mulling over right now. Is there or could there be such a thing as lesbian formalism? [Silence, then much laughter.]

Moyer: I can’t answer that question either. But I’m interested in thinking about it. Or do we just want to get away from ideas like that? Right now it seems like there’s a renewed interest in the connections between abstraction and identity.

A few months ago I was at an event sponsored by Feminist Art Project during this year’s College Art Association conference, and there was a whole discussion of it. As someone who’s made abstract art for a long time, is that something that you think about? Does it seem possible? Do you think it’s just in the work?

Fishman: I don’t think about it. But I think my identity is so intense that I’m

not making the paintings that a man makes. And I’m not making paintings that

a woman makes.

Moyer: You’re Monique Wittig?3

Fishman: Being of my generation, there wasn’t that kind of political framework around mark-making. So everything I did was mediated by my own experience rather than a broad discussion of gender.

Moyer: At the same time you viewed Abstract Expressionism as a gendered

form of painting. Because you weren’t allowed in? You weren’t allowed to play in the club.

Fishman: Yes, absolutely. Joan Mitchell was the only one who was allowed to play. She really had an independent stance—even though she was sleeping with

a bunch of them and she got screwed around. She was unusual. The norm was

the woman who came along with the guy artist. I had a friendship with her that started when we went on a trip to Paris. A friend of mine said, “Look up my friend while you’re there,” and gave me a piece of paper that had Joan Mitchell’s number on it. And I said, “You’re kidding me.” I was really intimidated, but she was very nice to me. She invited Betsy and me to her place in Vétheuil. When she came to New York, she’d invite me over. She told me much later that she thought I’d come to Paris to save her.

Moyer: What did she mean? From Jean-Michel Riopelle? From herself?

Fishman: Save her from whatever was going on that was so miserable for her. I was going to be her savior, and she put a lot on me.

Moyer: I’m sitting here looking at your new paintings and thinking about how you’re relating to the edge of the canvas, how much of the canvas gets left open.

Fishman: That’s a whole separate story. That’s something I’m very deliberately engaged in.

Moyer: I’m not even talking about influence. I’m talking about reference. Do these reference Mitchell?

Fishman: No, not at all.

Moyer: So you’re thinking about the structure of the painting?

Fishman: Yes, I’m looking to maintain more of the original drawing in a painting. There are times when I’m very troubled by heaviness or lack of breathing space in the canvas. Which happens periodically in my work because it’s very architectural, sculptural. It can be heavier than I want it to be. It’s not exactly who I am. It’s something I identified with for a long time. Almost like an armature to make architecture with.

Moyer: In your studio there are all these paintings with open, bare canvas in them. But if I were going to picture your work in my mind, I always think if it as being incredibly dense, almost impenetrable. There’s a lot of stuff under there if you look for it, but it has this I’m-not-going-to-let-you-in demeanor.

Fishman: That’s really been true. I wasn’t letting people into it. I’ve protected myself a whole lot, and I’m moving into an area where I’m wide open. My mother’s ninety-five and, if I hadn’t done this catalogue, her work would be in storage forever. I was looking at it and thinking, I have to open up my work. I have to put myself out there in a bigger way. I can’t act the way my mother and aunt did, and the way I learned to behave in the 1950s. A hider.

Moyer: A “hider”—what a great word. There’s a paradox embedded in these new paintings. The work has a kind of lightness but they are ostensibly about the Black Paintings. There’s an interesting seesaw between openness and kind of portentous drama. Do you know what I mean?

Fishman: Except that Goya’s Black Paintings have sky in them. And that’s what I’m looking to have.

Moyer: You mean this little corner? [Points to a painting.]

Fishman: Yes, it has an opening. And certain washes of paint allow you to move into it.

Moyer: You can stick your hand into the space. It’s loose and watery back there.

Fishman: It’s about looking at different things than what I’ve allowed myself.

It’s really an explosive thing. What I’m permitting myself is really amazing. Just

in time!

Moyer: That’s really pretty great. Just keep moving.

Louise Fishman has exhibited her work widely since the 1960s, most recently in solo exhibitions at John Davis Gallery (2012, Hudson, NY), and the Jack Tilton and Cheim and Read galleries (both 2012, New York City). Her exhibition It’s Here—Elsewhere is on view at Goya Contemporary (Baltimore) through April 5. The Neuberger Museum of Art (Purchase, NY) is currently organizing a retrospective of her work. Fishman is the recipient of a painting grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Guggenheim Fellowship in Painting, and grants from the MacDowell Colony and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, among others; her work is in an invitational exhibition at the Academy on view through April 14. She is represented by Cheim and Read Gallery.

Carrie Moyer is a painter and writer who has shown her work in the United States and Europe since the mid-1990s. The exhibition Carrie Moyer: Pirate Jenny is on view through May 19 at the Tang Museum, Saratoga Springs, New York, and will travel to the Columbus College Art and Design in spring 2014. Grants and honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship in Painting, a Joan Mitchell Foundation grant, and awards from Anonymous Was a Woman and Creative Capital, among others. She was one half of Dyke Action Machine!, an agitprop collaboration active in New York City between 1991 and 2008. Moyer’s writing has appeared in Art in America, Brooklyn Rail, Artforum, Modern Painters, and many other publications. She is an associate professor in the art department at Hunter College. Moyer is represented by Canada Gallery in New York City.

This conversation originally appeared in the Winter 2012 issue of Art Journal.