Aida Youth Camp of the Aida Refugee Center (Bethlehem, Palestine), Key of Return being installed, courtyard of KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2012 (artwork © Aida Youth Camp; photograph © Marta Gornicka, provided by Berlin Biennale)

In one of his best-known videos, the artist Artur Zmijewski is seen trying to persuade a former Nazi concentration camp prisoner to “renew” the number tattooed on the man’s forearm. In another film, Berek, naked adults play a game of tag in the gas chamber. But it is not the controversy about Zmijewski’s works that prompted his appointment as curator of the 7th Berlin Biennale, which took place at the KW Institute of Contemporary Art (Kunst Werke) and various locations in Berlin April 27–July 1, 2012. The official announcement issued by the Biennale’s Selection Committee in 2010 explains that the artist’s view on the “power of art and its relation to politics” was instrumental in its decision to hire him. In a number of texts and interviews, Zmijewski points to the weakness and inadequacy of contemporary art in the “production of political knowledge,” compared to how this knowledge is produced in other fields such as sociology and anthropology.1 The artist clarifies that his position aims to challenge the common belief that art is not capable of making a visible social impact because of its formal “autonomy”—what Zmijewski identifies as an inherent alienation. In order to lead contemporary art out of this self-imposed alienation, Zmijewski, in his artistic works, creates situations in which he uses individuals and their personal traumas as spaces of sometimes humiliating intervention. This constitutes his attempts to reinstate what he sees as the main value of art—its real autonomy, which implies a rebellion against moral constraints such as shame and guilt. No wonder many feared the artist would use his role as curator to continue his experiments with the limits of the already-strained borders between ethics, politics, and aesthetics. Ultimately, both Zmijewski’s critics and supporters got at least part of it right.

Martin Zet, Deutschland schafft es ab (Germany Gets Rid of It), 2012, installation view, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2012 (artwork © Martin Zet; photograph © Berlin Biennale)

In his curatorial statement, Zmijewski announced that the 7th Berlin Biennale (hereafter abbreviated BB7) would be a space of direct action, ready for the realization of projects “that possess the power of politics, not its fear,” and that are able “to change selected aspects of our shared reality.” He further stated that mere demonstrations of individual critical positions should be dismissed as uneventful, “empty“ gestures, to which Zmijewski opposed the “performance of politics”—the art of making reality and generating events.

Artists invited to take part in the BB7 offered examples of openly confrontational works of civil activism, striving to push boundaries whenever possible. In such works as Germany Gets Rid of It, for example, the artist Martin Zet displayed accumulated copies of a recent scandalous bestseller by Thilo Sarrazin, the title of which translates as Germany Is Doing Away with Itself.2 Sarrazin’s book is filled with racist commentary and Zet’s goal was to destroy every volume he acquired. Consider also Peace Wall, a barrier blocking an entire street constructed by Nada Prlja in order to critique both class segregation and gentrification in Berlin’s immigrant Kreuzberg district. (The wall was torn down when local residents protested.) Other confrontational works included Pawel Althamer’s video Sun Ray, in which the artist traveled to Belarus in order to commit an unlawful act involving nothing more than a group of people walking on the streets of Minsk. The piece shows a small, well-behaved parade of individuals, wearing reflective golden jumpsuits, openly challenging a dictatorial law restricting any kind of public protest including silent gatherings or strolling bands of peaceful people.

Nada Prlja, Peace Wall, 2012, installation view, Friedrichstrasse, Berlin, 2012 (artwork © Nada Prlja; photograph © Nada Prlja, provided by Berlin Biennale)

Then there was Jonas Staal’s New World Summit, an imaginary alternative parliament made up of political organizations that are currently on international terrorist lists. Zmijewski, with his cocurators Joanna Warsza and the Russian group Voina, also invited non-artists to participate in the BB7. Among them were Antanas Mockus, a former mayor of Bogota, Columbia, who is mostly known for employing artistic strategies in his government, and residents of the Palestinian refugee camp Aida, who used the Biennale as a space for asserting their right to reside on their native lands. The curators thus undertook a difficult task: to present projects conceived in various parts of the world as events of both political and aesthetic significance, while simultaneously attempting to avoid the usual traps of aestheticising politics, or politicizing aesthetics.

To some viewers, the BB7 seemed at first to offer no more than the usual experience of passive spectatorship, but with political gestures and a chance to interact with the works added into the mix. But closer consideration made it clear that the Biennale’s imperative was its “eventfulness.” In the exhibition’s press release, even the genre of the biennial exhibition was described as a ”repository of events.” While many participants and viewers found this concept overbearing, the real question presents itself: what exactly constitutes an event? The philosopher Alain Badiou insists that the issue is the foremost problem of our time. According to Badiou, truly “militant” (read: activist) practices in art were always born in the shadow of official political parties (communist, socialist, or anarchist).3 In this sense, art can be revolutionary and official at the same time only under conditions generated by a genuinely revolutionary state.4 In fact, a contemporary art of resistance is formed inside the system of the neoliberal state. This is why the opinion that it becomes more and more difficult to draw the line between official art and a position of resistance is by no means baseless.

Jonas Staal, New World Summit, 2012, installation view, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2012 (artwork © Jonas Staal; photograph © Marta Gornicka, provided by Berlin Biennale)

Artists, however, continue to be attracted by aesthetics and the practice of resistance. They do so even if they don’t belong to political parties, or if they don’t hold, or don’t think they hold, any ideology whatsoever. As the dissident Chinese artist Ai Weiwei insists in the documentary Ai Wei Wei: Never Sorry, “I am not a member of any party, I’m an artist.”5 The phenomenon of “revolutionary practices” of the 1960s still appears to be an unfailing source of inspiration for new generations of artist-activists. But one has to keep in mind that cultural projects such as Emory Douglas’s with the Black Panthers, or the street art of the Madame Binh Graphics Collective, emerged not only outside the art world, but also in direct opposition to the liberal welfare state of the 1960s.

Such is not the case for contemporary art, a brainchild of the late-capitalist, neoliberal world. When more and more artists embrace the necessity of revolutionizing not only art’s forms and means of production, but also its content, the question remains: how is it possible now to draw the line between an art of resistance to the dominant powers and art emerging within the agendas of institutions financed by corporate capital? Badiou proposes using the term “subjective determination” as a criterion for defining a genuine resistance: “In a militant art, ideology is a subjective determination, not of an artist, but of a process, or struggle, of resistance.”6 This position, Badiou clarifies, does not consider success in overtaking dominant systems of power as an ultimate goal. In relation to art, it means the dominance of presentation over representation. This crucial distinction comes from an awareness of “the contradictions between the affirmative nature of principles, and the dubious results of the struggle,” which often turns the opposite to its goals. A genuine “militant art” does not aim to take power. Instead, it means privileging pure existence, or what is becoming—not the result.7

Joanna Rajkowska, Born in Berlin, 2012, installation view, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 2012 (artwork © Joanna Rajkowska; photograph © Marta Gornicka, provided by Berlin Biennale)

In this sense, it is worth considering Zmijewski’s inclusion of a film by his fellow Polish artist Joanna Rajkowska, whose Born in Berlin documents her pregnancy and the birth of her daughter Rosa, whom the artist decides to deliver in Berlin. The apparent intention of Rajkowska’s film, made in the style of a home video, is to construct her daughter’s biography within a complex narrative involving tensions between Western and Eastern Europe. While the film does not contain any direct political claims, its presentation of the birth and the first months of the child’s life, as her mother prepares for the Biennale, appears to be a celebration of existence itself. The event of the exhibition is the event of the child’s birth. However, the story has an unexpected resolution. The newborn is diagnosed with a rare disease that can lead to blindness. It’s clear that Zmijewski interprets this malady as the child’s refusal to accept the narrative imposed on her. Although it’s difficult to agree with the curator’s thesis, which reduces one life to a metaphor, we can’t help note that such a development offers proof of Badiou’s idea that the undefined and unpredictable outcome is what constitutes the risk of a true event.

It is the presence of just such risk that has made the BB7 a target of relentless criticism. A short list of mantras from reviews published immediately after the opening include: “privileging artists’ political positions over aesthetics,” “staging the conflicts,” “cacophony of voices,” “false dichotomies” (such as action vs. inaction, object vs. performance), and so forth. Surprisingly, few seemed interested in looking into particular projects any more than they took time to observe the process of the exhibition itself. Meanwhile, to fully understand the curators’ intentions, or the authenticity of artistic activism presented at the BB7, required a minimum of a week’s engagement with the exhibition, its programs, and its educational seminars.

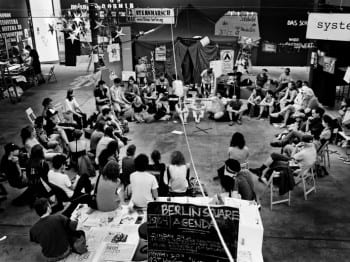

Indignados|Occupy, 2012, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (photograph © Marcin Kaliński, provided by Berlin Biennale)

The most controversial action of Zmijewski, Warsza, and Voina was perhaps “Occupy Biennale.” The participants of various social movements from Germany, Spain, and the USA—including the M15 Movement, Indignados, Occupy Wall Street, Real Democracy Now, and Arabian Spring—were invited to occupy Kunst Werke, which meant to install information booths and to set up an encampment inside the building’s gallery, where the art exhibition itself was primarily located. However, the curators’ idea to install “the open process of collective negotiations, debates, and decision making,” free from administration by official political institutions, seemed to commit the usual mistake, namely, replacing the experience of a social struggle with its representation. On the other hand, issues such as representation seemed unimportant to the curators. More important was the positioning of the artists and curators (and possibly viewers) in relation to the notions of “politics,” “autonomy” and the “effectiveness” of artistic practice. Indeed, last year’s Arab Spring revolutions and the Occupy Wall Street movement manifest precisely what contemporary art has tried to imagine for so long: an unprecedented rise in civil disobedience and political activism on a mass scale. In summer 2012, when the energy of Occupy Wall Street appeared to diminish, the activists moved from the noisy squares to quiet parks to discuss future strategies. The intention of BB7’s curators was to use the exhibition as quasi-public space for social activists to gather, converse, debate, and plan. Meanwhile, allowing activists to intervene in the traditional function of the Biennale, the main role of which is to provide space for exhibiting highly ranked art projects, was bound to raise more than a few questions for artists, activists, and administrators alike: Is it possible to introduce the experience of organizational horizonalism famously promoted by OWS into a major art event like the Berlin Biennale? Does not the petrified structure of such a global art institution, with its distinct hierarchies separating artists from curators, curators from Kunst Werke administration, and the KW from the city, mitigate against such radical leveling? How is it possible to even imagine curating and exhibiting a protest movement in the first place?

Draftsmen’s Congress, initiated by Pawel Althamer, 2012, installation view, Elisabeth-Kirche, Berlin, 2012 (photograph © Marta Gornicka, provided by Berlin Biennale) Visitors were invited to draw and paint on white panels placed throughout the church.

The BB7 curators were simply not very prepared to answer such questions. On the contrary, according to the testimony of the Occupy Wall Street participants, their general assembly meetings became little more than an extension of the exhibition on the upper floors, open to the viewers, interrupted from time to time by spectators or by visiting curator-stars who would leave the scene some five minutes later, disappointed with the tedium of “horizontal” discussions. Social processes are often slow and uneventful, unlike much contemporary art. All of this began to resemble an activist “zoo,” or as one of the participants described it, a “performative, political circus.”8

BB7’s curators seemed to be taking no lead in this process, limiting their own participation to silent observation. Still, to their credit, the Kunst Werke space was drastically different from newly fashionable concepts like the media lounge, in which a museum or biennial offers visitors a space to interact without ever soiling the sterility of the white cube. Located somewhere between the museum’s art galleries and crowded connecting corridors, these spaces are often painted bright colors and filled with cozy furniture, computers, and books, and noticeably marked by “special” design features that seem to say “come and play,” a strange invitation for traditional museumgoers. By contrast, the main organizational principles of the KW’s space was intended to facilitate general assembly meetings.

Teresa Margolles, PM 2010, 2012, installation view, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2012 (artwork © Teresa Margolles; photograph © Marta Gornicka, provided by Berlin Biennale) For a year the artist collected the front pages of the daily tabloid PM, published in Ciudad Juárez, a US-Mexico border cities.

In places it even resembled Zuccotti Park, including stacks of hand-lettered cardboard posters, and tables where brushes and buckets of paint were available for generating additional slogan-covered protest placards. The room’s walls were a neutral gray, perfect for allowing information to be chalked directly on its surface. The Kunst Werke space was further divided in sections. One was filled with tents for sleeping, another with the kitchen and canteen, still another dedicated to producing banners, and others provided spaces for web- and video-projection, a “99%” radio station, and a forum for presentations, discussion, and debate. The space unfolded into an urban backyard garden where the assembly participants could escape from the annoying stares of onlookers, and where the Autonomous University took place.

Participation by New York’s Occupy Museums appeared at first glance to resolve major semantic discrepancies between the idea of direct action, presumably the Biennale’s modus operandi, and its aesthetic significance. Occupy Museums, a subgroup of Occupy Wall Street’s Art and Culture working group, claims the right of the 99% to be included in contemporary art museums and institutions. It has mounted several effective picket lines and interventions in New York and typically deploys handmade and agitprop techniques to generate slogans and propaganda for its actions.9

The BB7’s imposed agenda and imperatives, however, turned out to be a serious challenge to the organizational horizontalism practiced by OWS. A collision was inevitable. The BB7’s limited time frame hampered the activist presence, as did a lack of clear goals, resulting in a mix of events such as unsuccessful attempts at introducing horizontal organization to Biennale employees. The occupation was nevertheless fulfilled, with public interventions staged at the Pergamon Museum using self-made student ID cards stamped with “Autonomous University,” a tactic first employed at MoMA.[1-. For video, see http://occupymuseums.org/. ] In retrospect, it seems that most Occupy Biennale participants agree that the BB7’s biggest failure was the way it emptied their social activism of its purpose through an overbearing agenda to produce events for the sake of satisfying the curators’ compulsions. It came to an absurd ending in case of the group of Brazilian taggers called Pixadores, which participated in Pawel Althamer’s project Draftsmen’s Congress. After the aggressive graffiti-tagging went beyond the designated space inside St. Elisabeth Church and began covering its facade, the BB7’s curators called on local police for help. As Blithe Riley, an Occupy Museums member, concluded in a private conversation with this author, “The curatorial choice to represent sociopolitical movements through a curated ‘occupation’—in a space that was quarantined and ripe with restrictions and power relationships between the ‘owners’ of the space and the occupiers—inherently made the representation performative and symbolic, and can be destructive to the movements.” Sadly, from being catalysts for urban social movements, the invited activists and artists groups were turned into the objects of curatorial experimentation, much in the spirit of Zmijewski’s own artistic projects.

Marina Naprushkina, Self-Governing, 2012, installation view, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2012 (artwork © Marina Naprushkina; photograph © Marta Gornicka, provided by Berlin Biennale)

Unlike Occupy Biennale, the works of several artists presented in the Kunst Werke galleries compensated for the lack of connections between the BB7’s political rhetoric and practice. Marina Naprushkina’s graphics, dedicated to a future for Belarus without its dictator Aleksandr Lukashenko, covered all three flights of the stairs, connecting the exhibition space above with the Occupy Biennale space on the first floor. Naprushkina is probably one of a few artists who embodied what might be described as the “political unconscious” of the BB7. Her works, along with those of Teresa Margoless and Rajkowska, are undoubtedly the BB7’s most successful projects.

Naprushkina belongs to the generation of artists formed by European neoliberal cultural politics. Her work reflects the aspiring political imagination of these newcomer states from peripheral Europe. But the actual social and political events in her native Belarus have borne significant consequences for her practice. On December 19, 2010, mass protests against rigged presidential elections were violently suppressed by police, and numerous Belarusian civil activists and opposition leaders were beaten up, arrested, and jailed. Ultimately, all political opposition to Lukashenko’s regime was eliminated. All these events generated a powerful, graphic response from Naprushkina, who now resides in Berlin but continues to direct projects into her troubled homeland. Without cutting ties to art exhibition, Naprushkina began to use the tactics of direct action. She collaborated with Nash Dom (“Our Home”), a nongovernmental organization (illegal according to Belarus state law) that disseminates printed materials—including graphic novels and illustrated newspapers that Naprushkina produces with help of cultural capital she often procures by participating in international art exhibitions.

Aida Youth Camp of the Aida Refugee Centre (Bethlehem, Palestine), Key of Return, 2012, installation view, courtyard of KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2012 (artwork © Aida Youth Camp; photograph © Artur Żmijewski, provided by Berlin Biennale)

Naprushkina’s work at the BB7, in which she imagines the country’s democratic development, was comprised of graphics wheat-pasted on the KW walls that included excerpts from her illustrated newspaper Self-Governing. (Copies of the newspaper were also included in the installation on the top floor of the KW.) Recently, the same material was disseminated by human rights groups, risking their members’ freedom inside Belarus.10

It is worth juxtaposing Naprushkina’s on-the-ground civil activism and another project at BB7 entitled The Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland (JRMiP). Produced by the Israeli-born artist Yael Bartana, the project calls for the return of 3.3 million Jews to Poland in order to “make an impact on the country’s future.” Naprushkina’s and Bartana’s works emphasize a moment when utopian political fantasies strive to be realized as actual social and political realities. Both projects originated in 2007—shortly before the global financial crisis manifested itself, and a year that for many signifies the end of the millenial collective utopias based on myths of economic prosperity in the Euro zone (attributed to the economic growth in Poland and even to notorious “stability” in Belarus). At the same time, the two projects employ different strategies. The three-day-long “First International Congress of the JRMiP: And Europe Will Be Stunned,” hosted by the BB7, remains in the realm of imagination—or perhaps we should say the realm of imaginative politics?—a sort of game played outside actual politics, though conceptually it has all the attributes of a political movement, including a logo, a manifesto, a set of rhetorical arguments, and a host of propaganda materials and discussions available online. By contrast, Naprushkina’s work functions both as an exhibition display and as an activist tool. Her graphic publications disseminate information pertinent to the political development in Belarus, where the autocratic government still uses the state apparatus to prosecute dissidents. The fact that her work is interwoven with the Belarusian social movement strengthened the visual presence on the walls of the Berlin Biennale. Some argue that the irony of Bartana’s art project, which mocks the propaganda style of the Israeli state, deals with deeply flawed national consciousness and works to suspend the state’s cultural certainties.11 In a peculiar way, the resulting uncertainy relates to the determination of the residents of the Aida Refugee Camp (whose Key of Return, a one-ton steel sculpture, was transported from Bethlehem to the BB7) and their determination to build a community around the notion of returning to their lost homes in Palestine. (The BB7 also hosted workshops in which the Palestinian youth in Berlin and Aida residents gathered to discuss the issue of homeland.)

Yael Bartana, Das Symbol der Bewegung Jüdischer Wiedergeburt in Polen entdeckt auf einem Markt (The Emblem of the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland Seen in a Market), 2011 (artwork © Yael Bartana; photograph © Nir Shaanani, provided by Berlin Biennale)

An analysis of the Biennale’s effectiveness (as formulated in the curatorial statement) suggests that events of such scale do have the potential to promote social movements and allow viewers to converge on both local and global levels. But there is always a danger that such momentum will be lost when organizers and curators take no lead in the activities’ development, and instead limit their role to administration, allowing, in OWS member Riley’s words, “curating to substitute for organizing.” As Riley also notes, the BB7 in most cases didn’t further the momentum: “They had the power to create a convergence, and they also had the power to articulate that convergence. By denying that power (which didn’t disappear—but in fact became more apparent) they weakened the potential of what BB7 could have been.” 12

If we assume, following Zmijewski’s statement, that contemporary art participates in the production of political knowledge, then the attempts of the BB7 to undertake something politically significant and eventful, to use Badiou’s terms, must go beyond mere glorification of the institution that produces it (which was clearly visible at the concurrent Documenta 13 in Kassel). Whether this knowledge turns out to be useful depends on whether the participants in such projects—artists, curators, viewers—can synthesize the experiences generated by the event while engaging in the elaboration of new ideas about social and political life, instead of coming up with techniques for its representation over and over again.

Bio

Olga Kopenkina is a New York–based, Belarus-born curator and critic of contemporary art. She has organized a number of exhibitions in the United States and Russia, exploring the relationship between art and politics. Since 2008, she has collaborated with Yevgeniy Fiks and Alexandra Lerman on the project Reading Lenin with Corporations. Kopenkina has contributed to publications such as Moscow Art Magazine, ArtMargins, Manifesta Journal, Modern Painters, and Afterimage, among others. She currently teaches at the Steinhardt School, New York University, and Moore College of Art and Design, Philadelphia.

- Artur Zmijewski, “Applied Social Arts,” 2007, at http://www.krytykapolityczna.pl/English/Applied-Social-Arts/menu-id-113.html. See also “Artur Zmijewski in Conversation with Liz Burns,” and Sarah Tuck, “Applying History,” in Fireside Conversations, ed. Burns and Leah Johnston (Dublin: Fire Station Artists’ Studios, 2009), 1–23. ↩

- Thilo Sarrazin, Deutschland schafft sich ab: wie wir unser Land aufs Spiel setzen (Munich: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2010). ↩

- Alain Badiou, “Does the Notion of Activist Art Still Have Meaning?” lecture, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, October 13, 2010, video at http://himanshudamle.blogspot.com/2010/11/alain-badiou-does-notion-of-activist.html. ↩

- Such states include the early Soviet Union, China, and the Republic of Cuba. From recent history, we might also include Argentina and Venezuela. ↩

- Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, dir. Alison Klayman, color film, 91 min. (Expression United Media and MUSE Film and Television, 2012). ↩

- Alan Badiou, “Does the Notion of Activist Art Still Have Meaning,” transcribed and ed. Marc James Léger, at http://interactivist.autonomedia.org/node/13795. ↩

- Ibid. In the same lecture, Badiou observes, “It’s an art of what has not yet been completely decided. It’s an art of the situation, and not an art of the state of the situation. Most importantly, it’s an art of the presentation and not an art of the re-presentation.” ↩

- I interviewed three members of the Occupy Museums subgroup of the OWS, who were invited by BB7: Blithe Riley, Jim Constanzo, and Maria Byck. ↩

- For details, see http://occupymuseums.org/index.php/actions. ↩

- One result of the campaign to disseminate the literature produced by Naprushkina was an arrest of a Belarusian human rights activist; see http://www.charter97.org/en/news/2012/7/12/55043/. ↩

- See Carol Zemel, “The End(s) of Irony,” Jewish Daily Forward, July 15, 2011. ↩

- Blithe Riley, e-mail correspondence with the author. ↩