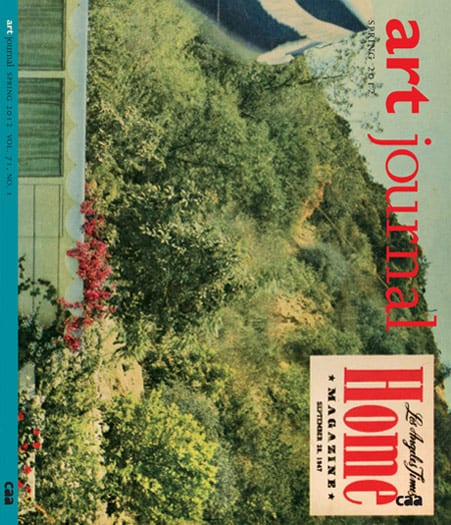

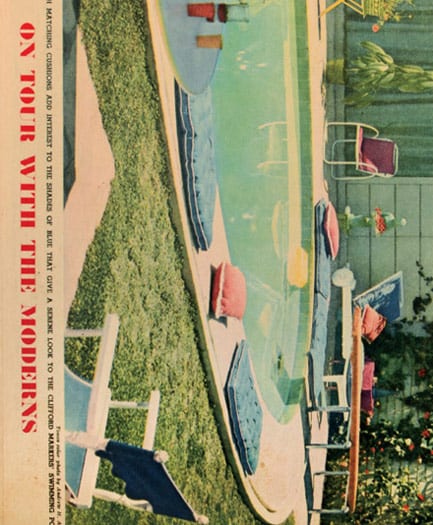

Allen Ruppersberg, PST: Before and After, 2012 (artwork © Allen Ruppersberg; cover photograph copyright © 1947, Los Angeles Times, reprinted with permission; interior background images published under fair use)

It can seem as if recent changes in how we learn do little more than facilitate a quantitative randomness. But the centrality of the Internet to intellectual work has made visible one under-recognized and revolutionary truth: the collective nature of creating knowledge. Bringing new information and new narratives into existence is an enormous and enormously difficult undertaking, best attempted by many people working together. This shared activity still happens largely with the support and under the umbrella of institutions. (Although, as I write this, it occurs to me that it is conceivable to do it without them, and I wonder why we don’t attempt this more often.) Institutional resources and focus are one reason that major museums have become central to scholarship and even to creating art, as well as displaying it; I hope that Art Journal has acknowledged this development, pointing to the dangers of agendas, but also to the possibilities of scale.

Over the past several years, any number of large art initiatives have taken shape, including Former West’s exploration of contemporary art in the context of a post-1989 world; the International Center for the Arts of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the investigation at the Haus der Kunst in Munich of the social landscape during and after World War II. Many of these projects—all of them curatorial, archival, and discursive in scope—revisit and revise understanding of late-modern geographies and politics, emphasizing the global or the transnational in place of national histories, in concert with the local. Seen from constantly changing present perspectives, history also changes. In this vein, one project in particular has promised to unsettle the understanding of art in the United States: Pacific Standard Time, the Getty-sponsored initiative exploring art in Southern California between 1945 and 1980.

This special issue on Los Angeles and Southern California art took shape in a bar in Brooklyn, where I met with Allen Ruppersberg in 2011. Despite his bicoastal status, Ruppersberg (who originally came to L.A. to study graphic design at Chouinard) is often seen as the classic Los Angeles artist. His early art, most famously Al’s Cafe (1969) and Al’s Grand Hotel (1971), but also his photographic books, was determinedly site-specific, capturing the structure as well as the affect of L.A. Highly influential, his work ended up constructing as much as reflecting its setting and the art produced there.

Allen Ruppersberg, PST: Before and After, 2012 (artwork © Allen Ruppersberg; cover photograph copyright © 1947, Los Angeles Times, reprinted with permission; interior background images published under fair use)

The images also speak of a particular history of art and artists, one that PST reflects: the strong presence of assemblage, followed by the ubiquity of high-gloss Pop and abstract painting and sculpture, followed by post-studio conceptual and performance art. Often the slightly faded pages from long-past magazine stories echo the brilliant, fresh images and text created this year (sometimes through sheer serendipity). Many of the same names appear again and again: Berman, Kienholz, Bengston, Irwin, Baldessari, Asher, and others. But PST also corrects the earlier record, moving the work and lives of artists who barely register in the previous iteration—Sister Corita Kent, Charles White, Eleanor Antin—from background to foreground. Beyond the recovery of individual artists that PST’s exhibitions and oral history program achieve, it establishes entire histories, including those of Chicano and black artists in Los Angeles, as well as nuancing our understanding of preexisting categories, such as post-studio. In so doing, these shows, catalogues, and research projects alter the larger, official, and too-often univocal history—not just California conceptualism, but Conceptual art looks different than it did before. “Different” is too weak; history complicated in this way is mind-opening.

Today, Ruppersberg has a certain distance from Los Angeles, reflecting his sense of the differences between the Los Angeles of the 1960s and the present moment—and also of the ways in which some things have not changed. This tension, and Ruppersberg’s awareness of all the issues entailed, as above, drives his project, making it not only amusing and beautiful to look at, but a sharp work of historical criticism. Like the artist, and like PST itself, all of the writers and scholars in this issue worked between Before and After. They reflect, correct, point to omissions, and reimagine. They critique the Getty initiative where they find fault, but also—acting as genuine critics—implicate themselves, acknowledging the impossibility of an outside in a community like Los Angeles (an outside traditionally assumed, if falsely, by critics). This issue of Art Journal also makes it clear why it matters to do history, beyond the peacock display of academic realness: while the work of PST ends in 1980, many of the authors locate the ways in which these new narratives inflect and are in fact themselves the product of work by people born perhaps after that closing date, returning us to the present.

I am grateful to all of the artists, critics, curators, scholars, editors, and the graphic designer who contributed to this issue. I hope that this intensive consideration of Southern California art and art history will serve as a model of engaged, collective work.