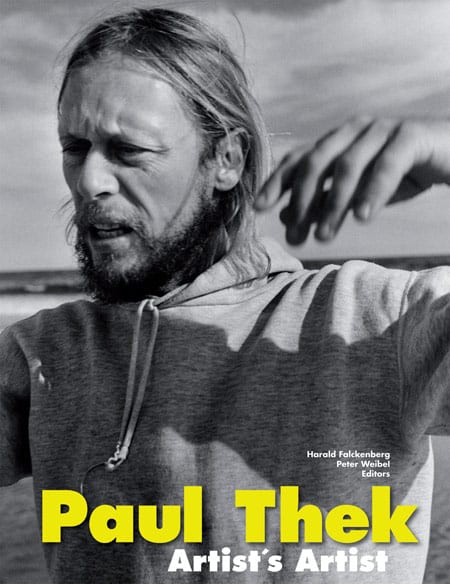

Harald Falckenberg and Peter Weibel, eds. Paul Thek: Artist’s Artist. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

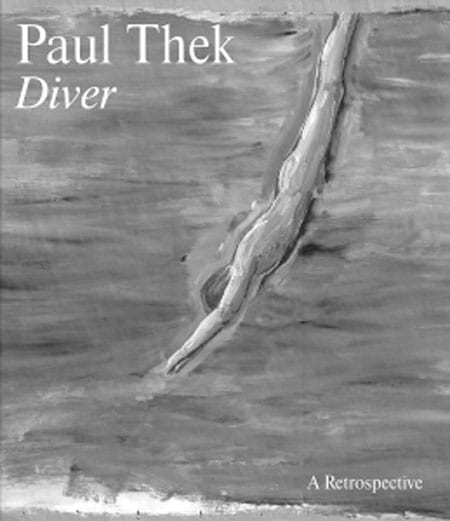

Elisabeth Sussman and Lynn Zelevansky, eds. Paul Thek: Diver, A Retrospective. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2010. 304 pp., 316 color and b/w ills. $65

Paul Thek: Diver, A Retrospective. Exhibition coorganized by Elisabeth Sussman, Sondra Gilman, and Lynn Zelevansky. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, October 21, 2010–January 9, 2011

Harald Falckenberg and Peter Weibel, eds. Paul Thek: Artist’s Artist. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009. 640 pp., 300 color ills., 200 b/w. $75

“What is alive cannot signify—and vice versa.”1 Roland Barthes’s pithy thesis from his seminal essay “The Reality Effect” (1968) reveals what might be called the vitalist basis of modernist indeterminacy. Countless artists in the 1960s would aspire to produce objects—and they were primarily objects rather than images—whose immediacy could rival that of natural things in the world. Whether invoking “literalist” strategies associated with Minimalism or transcending such “objecthood” through modernist self-reflexivity and “presentness,” the work of art in the 1960s was more often than not considered to be defiantly resistant to meaning, metaphor, and interpretation.2 At least that is the story we have been telling ourselves for quite some time now.

The enduring power of this account in part explains the general suppression of the work of Paul Thek (1933–1988) from the canon of postwar art. For Thek was nothing if not a figurative artist, one whose work, whether sculptural or pictorial, employed recognizable imagery. With its complex iconography, mythic allusions, and biographical references, Thek’s art invites a distinctly metaphorical and symbolic approach. Even though he is supposed to have inspired the title of his friend Susan Sontag’s book of essays Against Interpretation (which she dedicated to him), Thek’s art, even at its most erotic, insistently encourages a hermeneutics.

The recent Thek retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art and its accompanying catalogue, as well as a wide-ranging volume of texts by nineteen authors on the artist published by MIT Press, provide an opportunity to reconsider not only the artist’s career but his place within the history of postwar art, and in turn, the continued relevance of this inherited history itself. Both volumes endeavor to demonstrate two primary points: Thek’s status as “beyond doubt a major artist” (Artist’s Artist, 17) and “the singular and tenacious relevance of his art” to contemporary practice (Diver, 8), citing as evidence his proximity to art world inner circles in the 1960s—a rare moment when his work did receive a good deal of critical attention—and the way his works seem to prefigure central artistic practices of the last thirty years such as installation, performance, and time-based art. Following the tendency in contemporary art writing to consider artistic practices within preexisting historical trajectories (whether neo-avant-garde, avant-garde, or, occasionally, premodern), many of the essays in both volumes under review ironically seek to demonstrate Thek’s importance by diminishing his singularity. Occasionally these approaches yield consequential insights, as in Scott Rothkopf’s essay in the Diver catalogue, which convincingly situates Thek’s oeuvre within a strand of 1960s art that drew upon the “sexual politics of interwar Surrealism” (51), suggesting how the broader social politics of the decade played out in one realm of cultural production. Similarly, Margrit Brehm in her contribution to Artist’s Artist meticulously reconstructs Thek’s early exhibition history, locating his place within a series of intriguing and largely forgotten shows such The Obsessive Image, 1960–1968 (Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1968) and Figures and Environments (Walker Art Center, 1970) that productively complicate the conventional account of the period by demonstrating the heterogeneity of artistic practice in the 1960s. Yet if the singularity of Thek’s work has the virtue of revealing such obscured legacies and providing a missing genealogy for current practices, it was precisely the works’ eccentricity (as well as the artist’s equally eccentric personal behavior) that regularly prevented his art from garnering much critical esteem and commercial success during his lifetime.

Elisabeth Sussman and Lynn Zelevansky, eds. Paul Thek: Diver, A Retrospective. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2010.

In many ways Thek’s contradictory positions as both art world insider and maverick can be found in the body of work with which the artist first rose to prominence in the mid-1960s: the so-called meat pieces in which wax replicas of unidentifiable segments of flesh (taken from equally unidentifiable carcasses) were displayed in geometric Plexiglas containers. The tension between the disconcertingly mimetic entities and their sleek and occasionally translucent Day-Glo containers suggests Thek’s active role in complicating the dominant aesthetic paradigm of 1960s art practice. With their dually affective surfaces of wax and Plexiglas, Thek’s meat pieces sought the same sort of immediate presence as their Minimalist cousins (whose geometric and material precision were summoned forth in the cases), albeit through decidedly illusionistic means. When the artist used one of Andy Warhol’s simulated Brillo boxes as a receptacle for one of his carnal pseudo-relics, he literalized the anthropomorphic presence critics like Michael Fried saw in Minimal art. By transforming the postmodern work of art (whether a Pop simulacrum or a Minimalist “specific object”) into a framing device for his uncannily lifelike meat pieces, Thek handily deconstructed the sustaining modernist and postmodernist myths of immanence and materialism, demonstrating the fundamental mediation and imagination necessary to transfigure “things” into works of art.

Mike Kelley, in an essay written in 1992 that remains one of most astute assessments of Thek’s art (reprinted in Artist’s Artist), describes the relationship between the meat pieces and the Warhol box as “parasitic,” a term that could equally describe the artist’s broader conception of the relationship between art and life. As memorably depicted in his various paintings of pensive dwarfs who reside among columns of stock quotes from the International Herald Tribune’s financial pages, in Thek’s art the real in all its monotony frequently provides the sustaining backdrop for his visionary undertakings. Thek’s pictorial inventories of divers, volcanoes, mushrooms, and (as any parent of a young child knows) dinosaurs all straddle the boundaries between the real and the imaginary. As George Baker argues in his thoughtful analysis of Thek’s iconographic lexicon in the Diver catalogue, the artist’s various invocations of transformational imagery often led to certain forms of excess, as if the imaginary realm, once tethered to a more substantial ground, might take on a life of its own and become self-sustaining. Like the uncanny cords and sinewy wires that often extend beyond the Plexiglas cases of the meat pieces (beyond, that is, the aesthetic realm into that of life), Thek’s signature imagery repeatedly suggests the interrelated—and distinctly metaphoric—relation the artist sought to achieve between his art and its “host,” whether it be a literalist’s box or the white cube of the gallery.

This sort of spatial contingency would in many ways become the defining feature of Thek’s work in the 1970s as he staged an assortment of installations and events throughout Europe. Many of Thek’s installations mix seat-of-the-pants insouciance with a mythic and mystic grandiosity, looking like what might have happened if Joseph Beuys crashed his JU 87 in the Lower East Side and was rescued by dwarfs instead of Tartars. The two artists met at Documenta 4 in 1968, where Thek organized what he called A Procession in Honor of Aesthetic Progress: Objects to Theoretically Wear, Carry, Pull or Wave, a piece whose various regalia included a taxidermic buzzard and specially modified chairs with leather straps and cut-out seats that allowed them to be worn as headgear (at least theoretically). Much of the work was broken in transit from the artist’s studio in Rome to Essen, and the artist, either under the stress of deadlines or in a Zen-like acceptance of chance, chose to exhibit the work in its partially damaged state. Declaring that he would modify and complete the work throughout the run of the exhibition, he turned an installation that already suggested the remnants of a festive parade into an ad hoc performance whose incompletion became an essential component of its constitution.

The fragmentary, ephemeral, and ruinous character of so much of Thek’s oeuvre is most famously evident in what might be his masterpiece, the so-called Tomb of 1967 (later renamed—against the artist’s wishes—The Death of the Hippie). If Thek’s modified Brillo box exposed the vitalist basis of 1960s aesthetics, Thek’s Tomb, with its life-size wax cast of what appeared to be the artist lying dead on the floor of a wooden ziggurat, made the morbidity of the meat pieces explicit and personal. With its inscription welcoming visitors to what it declared to be “a replica of the tomb,” the work suggested that even at its most spatially engaging and visually mimetic, the artist’s work always operated in terms of symbolism and simulation rather than indeterminacy and immanence. Making the artist’s body the primary subject of the piece and yet presenting the subject’s eyes closed, tongue extended out, and fingers chopped off (and thus incapable of expression), Thek’s Tomb presented the artist as paradoxically present and absent, self-absorbed and egoless. It is consequently fitting that the work would over time take on its mythic status precisely through its gradual decomposition as it traveled across Europe from exhibition to exhibition until, as delineated in Axel Huil’s precise account of the itinerary of Tomb in Artist’s Artist, its ultimate disappearance in an American warehouse sometime around 1982.

While constantly integrating his life into his art, whether visually or through performative interventions, Thek would ultimately maintain a mythic, if not occasionally outright sacred, component in his art. He would expand upon this reliquary-like and ritualistic conception of the work of art in his Pyramid/A Work in Progress exhibition at Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1971 where, among other things, giant garden gnomes holding up a table amid a path of sand stood under a wax cast of the artist with fish tethered to the underside of a table hanging from the ceiling (just describing such works requires a breathlessness equal to the artist’s extensiveness). The artist’s interest in parades, processions, and relics (the meat pieces were renamed Technological Reliquaries sometime in the 1970s) suggests Thek’s characteristic understanding of symbolism as a form of agency. While it might seem perverse to interpret a parade as one would a traditional work of art, no one would deny the event’s significance or its social functions. Through the invocation of such ritualistic models of cultural expression Thek was able to find a means to produce what he saw as a meaningful engagement with life that nonetheless preserved art’s capacity to remain a special realm of experience.

As these examples suggest, Thek frequently aligned his art with unique temporal and spatial situations, a trait that makes a retrospective exhibition particularly problematical. The Whitney understandably (and in generally profitably) filled in these contextual lacunae with a variety of documentary elements, displaying open pages from the artist’s numerous notebooks, projecting photographs and films of the artist at work, and re-creating certain installations, albeit in a manner that openly acknowledged the distance between their original display and the current exhibition. The site-and-time specificity of Thek’s work is manifested in the “you had to be there” tone that frequently appears throughout the critical literature surrounding his work. In the catalogue, interviews and personal accounts by friends and collaborators compensate for the lack of material evidence, especially in the 1970s when Thek lived hand-to-mouth in various European cities, staging ephemeral performances and showing a remarkable disregard for the preservation of his objects. (Both volumes contain interesting accounts of the inherent challenges of conserving the artist’s works, both in terms of their material degradation and the question of respecting and discerning original artistic intent.) Thek was an active correspondent and diary-keeper, and many of his letters and journal entries are reproduced in the two books under review. Despite the occasionally inspired lines describing his passionate vision of the artist’s role, a large proportion of the letters (including those to Sontag) rarely rise to anything beyond gossip and occasionally present the artist as bitter and needy, writing desperate pleas for money and resentful barrages against those he thought were achieving the success he deserved.

More remarkable are the many paintings brought to light by the exhibition. Thek was throughout his career a prolific and occasionally brilliant painter and draftsman. When he returned to New York in 1979 after his peripatetic years in Europe, he focused on small painted works, primarily on his preferred support of newspaper, often installing them low on the wall in dime-store frames with elementary-school desk chairs in front of them, as if to suggest the ideal viewer for these exuberantly colored and deeply sentimental works. (Thek, one might argue, was always creating for a future audience rather than the one at hand.) If his loose and mannered amateurism resonated with the expressionist revival of painting in the 1980s, the overall modesty of scale and subject matter in his works provides a welcome riposte to the more grandiose aspects of that moment of postmodern painting. In his contribution to Artist’s Artist, Kenny Schachter perceptively identifies how Thek’s newspaper paintings partake in the underlying motif of decay within the artist’s oeuvre, aligning them with the meat pieces (a relationship further emphasized by Thek’s penchant for framing many newspaper paintings in Plexiglas). The exhibition makes a surprisingly strong claim for Thek as a painter, and perhaps it is in these works—which seem in many ways the least influential and celebrated of his oeuvre, but demonstrate most clearly such central themes as imagination, ephemerality, and marginality—that the essence of Thek’s artistic achievement can be best recognized.

While the Whitney exhibition and recent monographs effectively demonstrate Thek’s status as an undeniably talented and oftentimes pioneering artist, one is nonetheless left with the impression that he was a victim of circumstances (often by his own choosing), an artist whose disorderly life dictated the appearance if not the content of his work, for better or worse. With a little more money and ambition, what appears as a fragmented (both in the literal and figurative sense) and incoherent oeuvre might have matured more fully and found a more appreciative audience. Unlike an artist such as Gerhard Richter, whose stylistic heterogeneity is commonly regarded as a virtue, proof of his postmodern credentials, Thek comes off as an artist whose multifaceted explorations were as harried and half-baked as they were vibrant and numinous. Moments of true inspiration appear in unlikely places, such as in Thek’s notes for a course on four-dimensional design he taught at the Cooper Union in 1978. In them he presents a litany of aphoristic assignments ranging from the inspired (“Redesign the human genitals so that they may be more equitable”) to the utterly mundane (“Make a monkey out of clay”), suggesting how Thek’s importance is in some sense truly mythic, not really based on the extant body of work or even the remaining documentation, but rather found in the model of artistic existence he provides, one that is in many ways deeply romantic, vaguely spiritual, and, as Kelley notes, “gravely embarrassing.”

Perhaps it is ultimately Thek’s discomforting awkwardness that is both his greatest artistic virtue and his most potent legacy, sanctioning others to imagine unfashionable and embarrassing approaches and serving as a model for a career of altruism and integrity (attributes that, regrettably, seem to have their own embarrassing connotations these days). The disordered sprawl one experienced as both a visitor to the Whitney retrospective and as a reader of the two books is certainly a consequence of the artist’s own excessive and unwieldy aesthetic, and the projects feel at times to be compensatory and apologetic gestures by his critical supporters, as if extensive accumulation of historical documentation and scholarly analysis might self-evidently demonstrate artistic greatness. Although the MIT volume is certainly the most comprehensive account of Thek’s art to date (one can hardly imagine another book ever being published on the subject), readers will have to wade through a good deal of filler and uncritical tributes to retrieve the significant facts and valuable insights surrounding his life and work.

If, as Bazon Brock argues in his contribution to Artist’s Artist, Thek envisioned various “rescue strategies” (66) as models of artistic practice (such as redeeming the role of ritual in a secularized modern society), it is possible that such strategies are in some ways equally integral to the reception of the works themselves. Viewers of the Whitney exhibition were repeatedly asked to imagine and reanimate the remnants set before them. Such a mode of spectatorship might in the end not be that far from the central motivating force behind Thek’s artistic project, a point that accords with a statement by the artist that “one of the main functions of art is reanimation” (Artist’s Artist, 383). For if his interest in illusion and artifice, especially as they relate to the human body, suggests a desire for reanimation, fragmentation and incompletion would be precisely the formal catalyses for such an act. If we again find value in the art of Paul Thek, perhaps it is because we now find ourselves looking among the remnants of a postmodern, postutopian imagination, if that word can be used to describe our long-held (and generally well-founded) skepticism toward the realms of fantasy and myth. Long told to be wary of totalizing narratives and mythic sentiments, we may yet learn something from Thek’s “as if,” his celebration of an art that is at once alive and significant, if ultimately immaterial and virtual.

Robert Slifkin is an assistant professor of fine arts at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, where he teaches courses addressing various aspects of modern and contemporary art. His essays on the work of James Whistler, Philip Guston, Bruce Nauman, and Donald Judd have appeared in journals such as October, American Art, Oxford Art Journal, and The Art Bulletin.

- Roland Barthes, “The Reality Effect,” in The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 146. ↩

- These terms are from Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” Artforum 5 (June 1967): 12–26, rep. Art and Objecthood (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). ↩